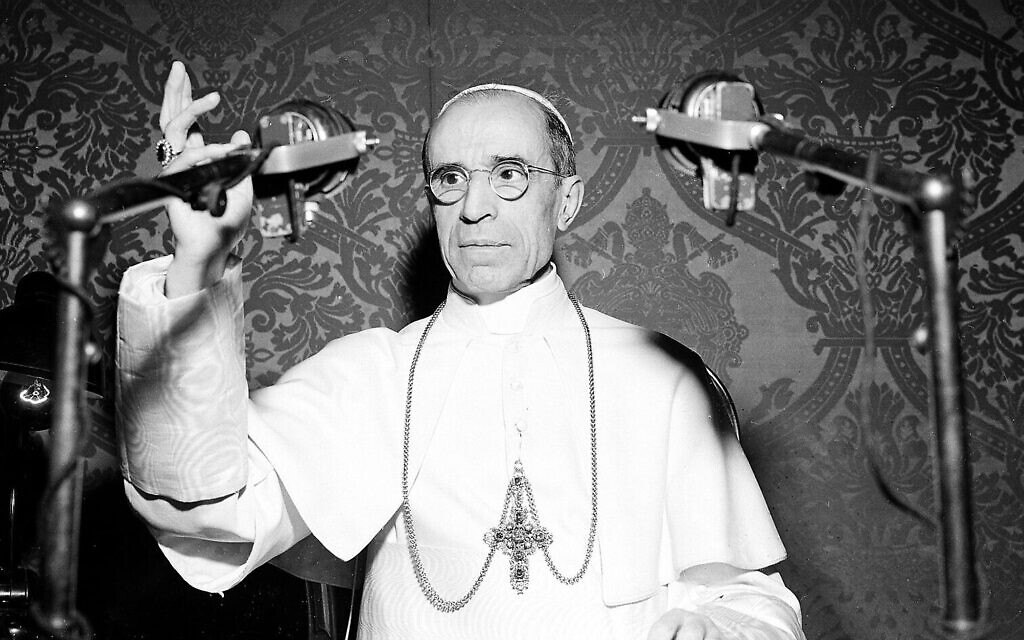

Pope Pius XII was no saint. The Vatican shouldn’t make him one.

The head of the Catholic Church during the Holocaust maintained good ties with Hitler rather than speak up as Jews were murdered

The time has come for the Vatican to end nearly 60 years of febrile speculation by confirming loudly and clearly that Pius XII – the wartime Pope whose legacy is irredeemably stained by his failure to confront the Nazi regime over the Holocaust – is no longer a candidate for sainthood.

The dispute over whether to beatify Eugenio Pacelli, the Italian cardinal who became Pius XII upon being elected to the papacy on the eve of World War II, dates back to at least 1965 when the Second Vatican Council debated the canonization of his liberal predecessor, John XXIII. The two popes became symbolic of a power struggle between progressives and conservatives in the Catholic Church, with Paul VI, the Pope at the time, pushing the cause of Pius. A stalemate ensued that lasted until 2000, when John was finally beatified. In the intervening period, however, there have been several attempts to elevate Pius to the status of a saint.

The last time the current Pope, Francis I, gave an opinion on this subject was back in 2014, when he was interviewed by journalists at Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv at the close of a two-day visit to Israel. While Francis confirmed that sainthood was not in the cards for now, alarmingly his reason had nothing to do with Pius’s wartime record.

“There’s still no miracle,” he stated. “If there are no miracles, it can’t go forward. It’s blocked there.” For a Pope to be beatified – an honor that has been bestowed on only 76 of the 265 pontiffs who have led the church – senior clergy must identify a miracle, something ostensibly unexplainable through scientific method, that he performed. If Pius’s supporters can successfully argue that a miracle was performed, as some of them tried to do a decade ago by citing the case of an Italian woman who claimed that his heavenly intercession had enabled her to survive a rare form of cancer, there is a real fear that he will become a saint irrespective of his wartime record.

[An] account of Pius’s actions…with regard to the Nazi extermination program was finally published last year.

The foremost problem with the historical debate up until recently has been the absence from public view of definitive documentation about the Vatican’s wartime role; locked out of its archives for decades, the many reputable historians and scholars who took one side or the other had no access to the critical records concerning Pius that were finally unveiled by Pope Francis in 2019, who declared as he did so that the Church should “not be afraid of history.”

Thanks to the opening of the archives, the authoritative account of Pius’s actions (or lack of them) with regard to the Nazi extermination program was finally published last year. The Brown University historian David Kertzer’s book “The Pope at War” garnered him a second Pulitzer Prize – he won the first for his study of Pius’s relationship with the Italian dictator Mussolini – and plenty of laudatory reviews, but astonishingly has made no impact on the deliberations of the two main parties to the dispute. On the handful of occasions that it has addressed Kertzer’s findings, the Vatican has been dogmatically defensive, while Jewish organizations and the Israeli government, understandably nervous about rocking their warm relations with the Catholic Church, have failed to call on the papal authorities to acknowledge the truth about Pius and end, once and for all, the canonization process.

Kertzer’s chief contribution has been to explode the myth, sustainable for as long as the Vatican archives were closed, that Pius refrained from speaking out on the plight of Europe’s Jews because doing so would have worsened their situation. But there is no longer any excuse to defend a Pope who, as Kertzer writes, manifestly failed “ever to clearly denounce the Nazis for their ongoing campaign to exterminate Europe’s Jews, or even allow the word ‘Jew’ to escape from his lips as they were being systematically murdered.”

That does not mean that Pius did not privately disapprove of the Nazi persecution nor make his objections discreetly clear in personal encounters. What Kertzer shows us, though, is that Pius’s direct back channel to Hitler opened early on during the war made him even more wary of displeasing the Nazi dictator. For example, he relates how, when the Nazis began rounding up Rome’s Jews under Pius’s very nose in October 1943, the pope sent an emissary to the German Ambassador at the Vatican to inquire whether the operation was strictly necessary at that moment. When the Ambassador explained that the round-up had been ordered by Hitler himself and asked whether the Vatican still wanted to protest, Pius’s emissary demurred.

Ultimately, Pius made a conscious decision from the beginning of his papacy to prioritize the retention of good relations with Mussolini and avoid offending Hitler, in order to “plan for a future in which Germany would dominate continental Europe,” as Kertzer writes. Yet as the fortunes of the war began to change in 1942 with a series of Allied military victories, Pius still stuck to his initial assessment. Closing his book, Kertzer acerbically observes that at a “time of great uncertainty, Pius clung firmly to his determination to do nothing to antagonize either man. In fulfilling this aim, the Pope was remarkably successful.”

If the Church really has no reason to be “afraid of history,” then it must register the full measure of Kertzer’s painstaking research. Eight decades after the war ended, much has been achieved to bring about a historic reconciliation between the Catholic Church and the Jews, but that project will remain unfinished for as long as Pius’s beatification remains a possibility. What’s needed from Church leaders and Jewish leaders alike now is the quality Pius sorely lacked: courage.

––

Abraham Foxman served as national director of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) from 1987-2015.

Ben Cohen is a New York-based commentator who writes frequently on Jewish and international affairs.

There's no paywall on The Times of Israel, but the journalism we do is costly. As an independent news organization, we are in no way influenced by political or business interests. We rely on readers like you to support our fact-based coverage of Israel and the Jewish world. If you appreciate the integrity of this type of journalism, please join the ToI Community.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel