Jewish schools need staff, Arab teachers need jobs – but it’s not so simple

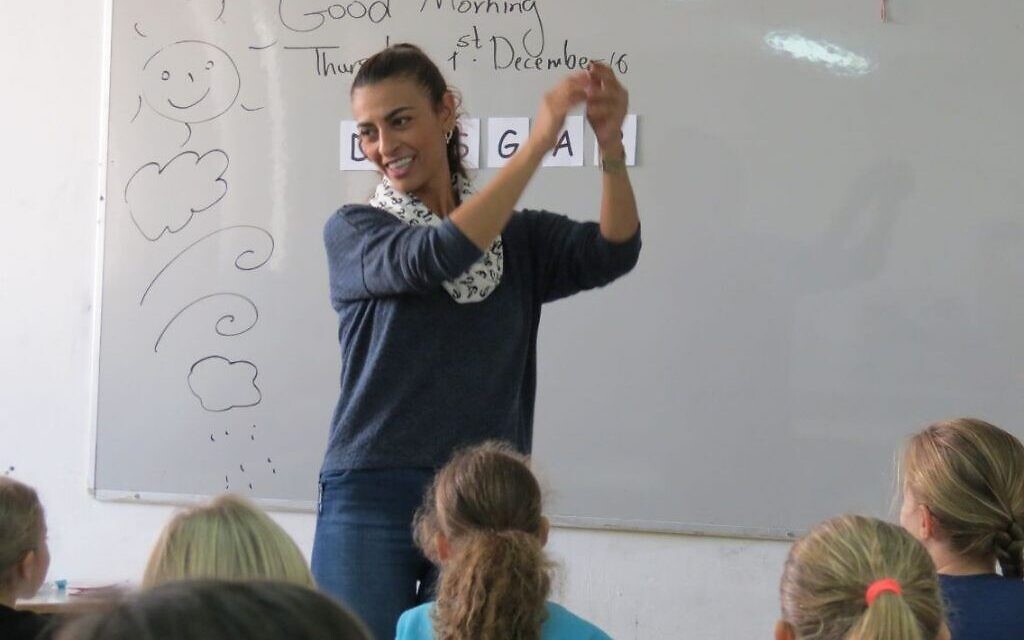

Only 1,200 Arab educators are employed in Jewish public schools, where there are numerous vacancies. But to succeed in Jewish schools, they need a lot more than good Hebrew

With the school year about to end, Israel’s Jewish education system is still short thousands of teachers. At the same time, the Arab community is seeing a massive surplus of teachers, with as many as 11,000 estimated unemployed.

Though a solution to the years-long staffing crisis may seem obvious – provide additional training so Arab teachers can be hired to fill the gap in Jewish schools – the Education Ministry has yet to adopt such a measure on a significant level.

Plans to integrate unemployed Arab teachers have been around since a first program was launched by the Education Ministry in 2014, but have been implemented only on a small scale that far from meets the need.

Instead, the ministry has opted for other steps, some of them drastic, including hiring retired teachers and educators who do not meet all the requirements, and opening fast-track training programs for academics and former instructors from the IDF Education Corps. Teachers already in the system have also had to make up some of the slack, with reports of school principals increasing teacher workloads by up to 150 percent.

Some 1,200 Arab educators are currently employed in Jewish public schools, the Education Ministry told The Times of Israel. A spokesperson said the ministry plans to expand existing programs to increase the number of eligible teachers, and to pave the way for more Jewish schools to hire them.

“Hundreds of Arab teachers are already working in Jewish schools, and they have proven to be a success story — from a pedagogical standpoint, in their relations with students, and in breaking stereotypes,” said veteran Knesset member Ahmad Tibi, head of the Ta’al party. Increasing that number, he added, would be a “win-win” for both Jews and Arabs.

But filling staff shortages in Jewish schools with unemployed Arab teachers is easier said than done, according to Dr. Salim J. Munayer.

A series of obstacles

An adjunct professor at Hebrew University’s School of Education, and an expert in the Arab education system, Munayer pointed to the main obstacles to placing Arab teachers in Jewish schools: “First, in order to work in a Jewish school, Arab teachers not only need to be fluent in Hebrew, but also need training in cultural mediation and in how to dialogue with Israeli Jews.”

Currently, the largest project for the integration of Arab teachers is “Meshalvim u’Mishtalvim” (“Hire and Integrate”), run by the Merchavim Institute in cooperation with the Education Ministry and the Social Equality Ministry.

The program helps Arab teachers improve their Hebrew language skills and familiarize themselves with Jewish Israeli society with a view to being hired by a Jewish school. The institute also has a direct placement program for teachers who already meet the requirements.

Munayer, who is the founder of Musalaha, a faith-based organization promoting reconciliation between Israelis and Palestinians, stressed the importance of Arab teachers also being able to handle conflict while working in a Jewish environment. “Conflict mediation is as important as knowing Hebrew, because conflicts can arise in the classroom at any time,” he said.

Another obstacle, according to Munayer, is pushback from students and parents, especially in more conservative areas: “Arab teachers today are more likely to be hired in a progressive city such as Herzliya or Ramat HaSharon than in a conservative city like Jerusalem.”

He cited research and anecdotal evidence indicating that parents and students often question the credentials of Arab teachers and the quality of their instruction, especially in the current atmosphere of what he called “polarization and radicalization.”

To be able to work, a teacher needs to feel comfortable in their environment, and not be constantly questioned or tested to see if they are a “good Arab,” or loyal to the country, he added.

A survey commissioned by the Haifa-based Gordon Academic College of Education in 2016 found that 41% of Jewish parents were opposed to their children being taught by Arab teachers; among Jewish religious parents, 82% were opposed.

According to the study, Jewish parents were wary of Arab instructors conveying core Zionist values and teaching about significant dates in the Israeli calendar such as Memorial Day and Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Finding a balance

Integration is more likely to be successful if the Arab teacher is hired for a subject like English, math or chemistry, rather than a “sensitive subject” like history, said Munayer. “The historical narrative in a Jewish school is pretty much Zionist; it’s a Jewish historical narrative mandated by the Education Ministry that leaves no place for the Arab and Palestinian narrative and heritage, and that can be difficult for Arab teachers to accept,” he said.

The sentiment was echoed by May Arow, one of the founders of “Ya Salam,” a program that teaches spoken Arabic in elementary schools. The program, which was launched by the Abraham Initiatives group in 2007 and then taken over by the Education Ministry in 2016, has been running in 200 schools throughout Israel, both secular and religious. In its original design, “Ya Salam” aimed to train Arab teachers to become instructors of Arabic language and culture, while simultaneously preparing them to work in a Jewish Israeli environment.

Arow, herself a former teacher in a Jewish school, agreed that cultural awareness is a major element when training Arab teachers to work with Jewish schoolchildren.

“An Arab teacher often does not have the skills to function in an environment with very different cultural codes,” she said. “If they are not aware of them, they will easily be disrespected by their students. Furthermore, during times of security tensions, when animosity between communities is running high, teachers should not ignore the situation, but rather explain to their students how both Jews and Arabs are affected by it. And when feelings of hostility arise in the classroom, it is important first of all to acknowledge them, and not shut them down.”

She also said that as a “token Arab” in a Jewish school, a teacher will often be under scrutiny and may be asked questions by students and staff if, for instance, they don’t sing the Israeli national anthem. “Communication between teachers, the school principal and students is key in these cases, and a balance must be struck between respecting the Jewish Israeli environment of the school, and the teachers’ personal background and sentiments,” she explained.

Two steps forward, one step back

Israeli universities and academies produce a surplus of Arab teachers, mostly women, to the point that most of them cannot find a position in the Arab education system. Often, they are forced to teach in schools far from their homes, or to abandon the teaching profession altogether after years of study. According to a Knesset report from January 2023, only a little over half of Arab graduates in education actually manage to find a teaching job.

“We also see many Arab teachers who don’t feel they are suited to teach in a Jewish school, for various reasons,” said Yael Keren-Raba, director of educational programming at the Merchavim Institute. “Many of them live in the north, where most of the Arab population is concentrated, and are not willing to get a job in central Israel, where most vacancies are found, especially because travel costs for teachers are not covered by the schools.”

Approximately 1,000 certified Arab teachers apply annually to “Meshalvim u’Mishtalvim” to be integrated into the education workforce in Jewish schools. However, the main obstacle to the expansion of the program, according to Keren Raba, is language proficiency.

“We receive many applications each year, but less than half of the applicants pass the selection stage,” she said. “Many Arab educators do their teacher training in Arabic, and don’t have an adequate level of Hebrew to teach a class of Jewish children.”

Teachers who are accepted to the program and cannot find a school placement on their own undergo a two-month orientation, during which they improve their Hebrew language skills, both written and spoken, familiarize themselves with Jewish history, tradition, and holidays, and undergo intercultural training.

The program’s success rate is high. Over the course of the 2022-2023 school year, 262 teachers found a job, out of around 300 who attended the orientation course. They were hired by the 240 schools throughout Israel that participate in the program, and teach mainly English, math, science, sports, arts and civics. A few even teach Hebrew literature and Bible studies. Some of them have advanced to become class-level coordinators, administrators and principals.

Keren-Raba admitted that tensions can surround specific subjects related to Zionism and Israeli history. While many Arab teachers are open to discussing Independence Day and Memorial Day in class — after all, a spokesperson for the Education Ministry said, “it is the teacher’s choice to work in a Jewish school” — others prefer to take a day off on those occasions. The Merchavim Institute, in cooperation with the Education Ministry, organizes special workshops ahead of commemoration days and during times of heightened security tensions, when some Arab teachers are afraid to enter Jewish cities and the classroom atmosphere is tense.

“Whenever the country goes through a period of security tensions, suspicion resurfaces between the two communities, and the integration becomes more difficult,” Keren-Raba said, echoing May Arow’s comments.

Arab teachers placed by Merchavim who have worked for over two years in the same school also have an opportunity to become “intercultural ambassadors,” said Keren-Raba. “Their presence in the classroom is an opportunity for Jewish students to learn about Muslim and Christian holidays,” she noted, “as well as Arab traditions, elements of which can be inserted in the educational curriculum — for instance, in science class students learn about the tradition of olive harvesting in Arab society.”

The integration program began in 2014 with 10 teachers and has grown to about 300 yearly. “We are doing all we can, in cooperation with the Education Ministry, to advertise the program to school principals and Arab teachers and increase the number of participants,” Keren-Raba said.

Finding placement for the teachers continues to be a challenge, though.

“We have come across school principals who are not willing to take on the challenge of hiring a teacher from a different culture, because they are concerned about potential backlash from parents and staff,” she said. “Sometimes we feel we take two steps forward and one backward.

“The integration program is effective in the short term in providing educators to Jewish schools, and in the long-term in breaking stereotypes and promoting coexistence. Wherever it is implemented, we see that the response by students and parents is largely positive. But it has its limitations. For the time being, unfortunately, it cannot be the only response to the teacher shortages.”

There's no paywall on The Times of Israel, but the journalism we do is costly. As an independent news organization, we are in no way influenced by political or business interests. We rely on readers like you to support our fact-based coverage of Israel and the Jewish world. If you appreciate the integrity of this type of journalism, please join the ToI Community.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel