What Matters Now to Yair Zakovitch: Using ‘Ruth’ as a blueprint for creative halacha

Israel Prize-winning Bible scholar dives into Shavuot scroll’s meaning, laments lack of biblical literacy in secular society, but sees hope in anti-judicial overhaul demonstrations

Welcome to What Matters Now, a weekly podcast exploration into one key issue shaping Israel and the Jewish world — right now.

This week, Jews all over the world will mark the holiday of Shavuot by reading from the Book of Ruth. In this biblical tale, disaster and famine strike and an elderly widow called Naomi loses her two sons. Now childless, she tells her daughters-in-law to return to their parents’ homes in Moab and says that she will make her own way back to her family in Bethlehem.

One daughter-in-law, Orpah, regretfully leaves. The other, Ruth, says the famous lines, “Where you go I will go, and where you slumber I will slumber. Your people will be my people and your God my God.”

And with that, she joins the People of Israel and eventually becomes the ancestor of King David.

The Book of Ruth was written about 2,500 years ago. However, argues our guest this week, it couldn’t be more relevant today as a model of “creative halacha.”

Israel Prize-winning Bible scholar Prof. Yair Zakovitch joined The Times of Israel this week in his book-lined Hebrew University office to discuss the societal context of the Book of Ruth and the halachic “problems” it solves.

The author of best-selling works on the Bible was born in the pluralistic northern city of Haifa in 1945 and joined the faculty of Hebrew University in 1978. Awarding him the Israel Prize for Bible in 2021, then-education minister Yoav Gallant said, “Yair Zakovitch is one of the most original Bible researchers in the country and the world.”

To bring the Bible to the next generation, Zakovitch helped found the Hebrew University’s Revivim program, a prestigious teacher-training program for outstanding university students who sign on to teach in state schools post-graduation.

In our in-depth conversation on the Book of Ruth, we hear how the scroll’s author — in opposition to the writers of the contemporaneous prophets — offers a scripture of compassion in solving that era’s challenge of intermarriage.

We also hear about today’s rampant biblical illiteracy and why it is immensely important for secular Israelis to readopt the Bible for themselves.

This Shavuot week, we ask Prof. Yair Zakovitch, What Matters Now.

The following transcript has been lightly edited.

The Times of Israel: Yair, thank you so much for allowing me to join you in your beautiful office at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Mount Scopus campus.

Yair Zakovitch: You’re very welcome.

Thank you so much. We’re here to talk about the Book of Ruth ahead of Shavuot — of course, it’s read on Shavuot — but I wonder, is it still relevant today? So I ask you, Yair, what matters now?

The Book of Ruth is very, very relevant for our times because it’s all about intermarriage and about halachic creativity, something which is very necessary nowadays.

And maybe rare even.

Oh, yeah.

So let’s dive into the Book of Ruth and talk about its dating. When do you think it was written?

Well, it’s very important, actually, to date the Book of Ruth, because only if we find the date can we understand what the context was, what the social context was, the halachic context of that time. So the Book of Ruth was actually written at the time of the Return to Zion about the fifth century BCE. Something like that.

And how do I know that it was written that late? First of all, the language. The language is very different from the Hebrew language of the First Temple time. But there are many other reasons. First of all, Ruth is a perfect person. There are no perfect people in biblical narratives written in the First Temple period. And secondly, Ruth is a woman. The book is named after a woman. Only, again, in later times, there were books written about women. The Book of Esther, of course, the Book of Judith, which was not included in the Hebrew Bible, and then Susannah, which is actually one of the additions to the Book of Daniel, which we find in the Septuagint.

But something else, the location of the book [in the Hebrew Bible]. I know for sure that the author of the book intended, wanted, it to be put between Judges and Samuel. How do I know it? If you look at the end of the Book of Judges, the last story there about the concubine from Gibeah, it’s about a woman that leaves her husband and goes to Bethlehem. She’s quite selfish, leaving her husband to go to Bethlehem. Ruth then, is the opposite. Ruth goes to Bethlehem because she’s an altruist. She left her family and followed her mother-in-law to Bethlehem.

But of course, the Book of Ruth should have been put next to Judges, because how does it start? In the days of the judges. And then if you look at the end of the Book of Ruth, you see that it’s related to the very beginning of the Book of Samuel. At the end of the Book of Ruth, in chapter four, verse 15, we read about the baby that has been born. “He will renew your life and sustain your old age. For he is born of your daughter-in-law, who loves you and is better to you than seven sons.”

Pay attention to the end of the verse, very similar to what we have in the first chapter of the Book of Samuel. When Elkhana, the husband of Hannah, is saying to her, “Hannah, why are you crying? And why aren’t you eating? Why are you so sad? Am I not better to you than ten sons?” There are no other verses in the whole Bible that are similar to these two verses.

So what the author of the Book of Ruth has done is what we know now in modern medicine, transplanting organs. If you want to transplant an organ, you have to make sure it won’t be rejected. So the author made sure it will be well attached to the end of Judges and to the beginning of Samuel.

And of course, if we put it before Samuel, don’t forget that the Book of Ruth ends with the genealogy of the House of David. And that’s a great introduction to the Book of Samuel, because in the Book of Samuel itself, we don’t have a genealogy of David. We know who his father was, but we don’t know who his grandfather was, et cetera. So here we get a great introduction.

So the author wanted it to be put between Judges and Samuel, but it didn’t work. Why didn’t it work? The process of collecting the books of the Bible, putting them together, was a very slow process. And that part of the Bible — the Torah and what we call now the early prophets — that part was already closed. It was impossible to add anything to that part. So it’s as if the author came to the publisher with his book and he was told, “No, we are not in business anymore. Cross the street. Perhaps there there is another publisher, a new publisher, Ketuvim [Writings]. Try your luck there. And that’s what happens.

So many questions, if I may jump in.

Yes.

Number one, when was the canonization completed for the prophets?

The canonization of the Prophets didn’t end again before the Second Temple period. For instance, the last prophets in the 12 minor prophets — you have Hagai, Zechariah, Malachi, who are all from the times of the Return to Zion. So that’s why I said that the Book of Ruth could not have been included in the early prophets because the early prophets was already closed, that part. But the part of the other prophets was still —

But in other religious traditions, it is slotted into the spot that the author intended it to be.

Yes, of course in the Septuagint, and then, of course in the Christian Bibles, that’s where it is. The order of the books in the Septuagint, for instance, is much more logical than the Hebrew Bible. They could play with it, move it, put it in the right place, but it was impossible because of the process of canonization. It was impossible to do it in the Hebrew Bible.

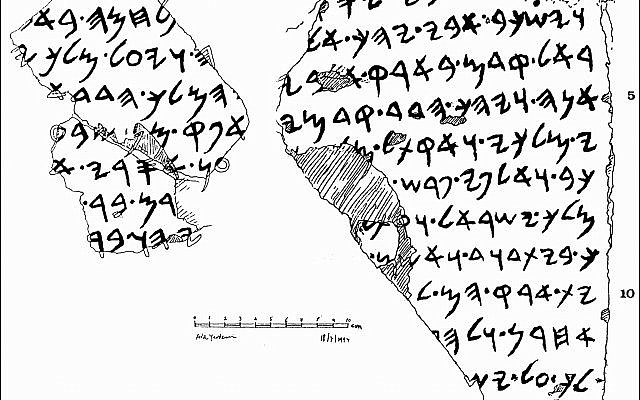

I wonder if you can give us a couple of examples of the use of language that you use to date it to the period that you suggest.

Yeah, I’ll have to use Hebrew here: In the Book of Ruth, it’s naso isha — you marry a woman. In the early Hebrew language, it’s lako’ah isha you take a woman. Or shalof na’al taking off a shoe. In the early language, sha’al naalecha, et cetera. Or for instance, the root agon that appears, nashim agunot, et cetera, appears only again in late biblical Hebrew.

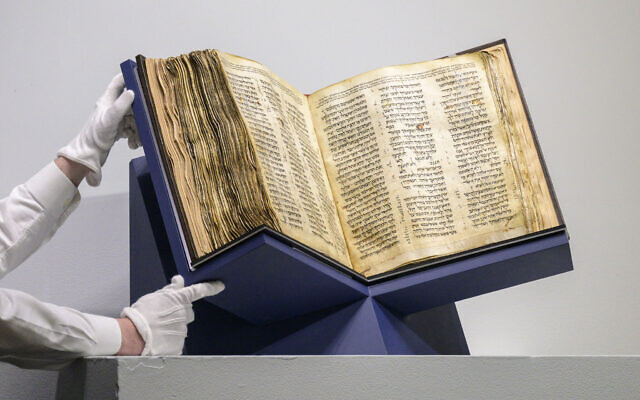

The “anchored woman” concept that we have today… Okay, very interesting. And in the copies that we find in the Dead Sea Scrolls, do you see any differences in language to what we have in our regular standard Hebrew Bible?

It depends. In the Dead Sea Scrolls, there are two types of biblical scrolls. One type follows the language the way it was. If you copy a book of an early biblical book, the language will be exactly the way it was. But there are what we call “vulgar scrolls,” in which the language was changed many times. So people of that time, when the scrolls were written, would understand the biblical text. So there you see late biblical Hebrew or late language in early books.

So we’ve dated it and we’ve talked about why it’s not placed with the Judges. Now, you alluded to this earlier when you talked about Ruth as a perfect person. And I’m not a scholar of any sort, but I always like this book because it seemed to talk about really ordinary people, not perfect. I mean, she’s poor, she’s ordinary, she’s common. So what makes her and the people in this book perfect?

Look, she is perfect. What else can you say about a woman that leaves her family behind, moves to a country she has nothing to do with the people there, with the language, with anything. Following her mother-in-law, that’s a miracle. Following one’s mother-in-law!

And again, if you compare it to the other daughter-in-law, to Orpah. She is also a very nice person. She was also interested in leaving her world and moving with Naomi to the new world. But Naomi convinced her, in the end, to stay where she was. So you see, one is almost perfect and the other is more perfect. And the very same happens at the end of the book. There is the closer relative, hagoel, who was ready to redeem the field of Naomi. The moment he heard that he has also to get Ruth in the transaction, he refused to do it. He was almost perfect. He was willing to fulfill a mitzvah, but Boaz is more perfect than him. So, you see, Ruth and Boaz are actually perfect.

And because they’re perfect, they can have King David as a descendant.

Yes, of course. That leads, of course, to the birth of King David. And God is very pleased with what has happened.

Okay, so you talked about the idea of redemption, the redemption of the field, and I never quite understood this part, because it doesn’t seem to 100% jive with what we learn in the Torah.

Okay, now we get to a very interesting point. The Book of Ruth does not follow exactly the halacha of the Torah, because if we follow the halacha of the Torah, nobody is allowed to marry a Moabite woman. And indeed, that’s why it was so important for me to tell you what the date is, because if we get to the Second Temple period time, the time of Ezra and Nehemiah, we find a quotation in Nehemiah, chapter 13. We read, “At that time, they read to the people from the Book of Moses, and it was found written. ‘So no Ammonite or Moabite might ever enter the congregation of God,’ et cetera, et cetera.

That’s a quotation from the Book of Deuteronomy, chapter 23. “No Ammonite or Moabite shall be admitted into the congregation.” So Ezra and Nehemiah wanted to follow the Torah the way it is. There was no flexibility there. And in that time, there were many Jews married to foreign women, to Moabite women, to Ammonite women. And that’s the real problem of the Book of Ruth.

The problem that the book is trying to solve. Is that what you mean?

Exactly. You know that when Ruth gets to the field of Boaz, she asks him, Why does he treat her so nicely? And she said, I’m a foreigner. And the whole book is an answer to this question. So how does the Book of Ruth solve the halachic problem? It does it very slowly.

First of all, we can start by when I said that Ruth asked this question, Boaz is telling her, “I have been told all that you did for your mother-in-law after the death of your husband, how you left your father and mother and the land of your birth and came to a people you have not known before.”

I’m sure that you see or you hear that this verse is very, very similar to the very beginning of the story of Abraham. How God tells Abraham, “Go forth from your native land, from your father’s house to the land that I will show you.” So immediately we realize that, wow, Ruth is as good as Abraham. But if we stop for a moment, we’ll realize that she is better than Abraham because Abraham was commanded by God to do it. She was not commanded by anybody to do it. So immediately you realize that Ruth is wow. She is, as I said, perfect.

Then, toward the end of the book, Ruth is compared to the other mothers of the people of Israel, to Rachel and Leah. Again, it’s great. So the author of the Book of Ruth is using biblical stories, mainly from the Book of Genesis, to show you how great Ruth is.

But we have a problem because when we think about Moabites, we immediately think about the story — we can’t avoid it — we immediately think about the story of the mother of all Moabites, the story of Lot and his daughters. And that’s a terrible story.

The daughters of Lot, they should have asked their father, who would have told them that it was not a world catastrophe, just a local one. They didn’t ask. And they made this plan. Actually, the elder one, the mother of the Moabites, she made the plan. They slept with their father, et cetera, et cetera, because they thought that there was nobody in the land or in the world to get married to them.

So we need a vaccine for this disease. What will we do? So we build the story of Ruth, especially the third chapter in the Book of Ruth. So it shows you how much better Ruth is than the mother of all Moabites. And you cannot judge her the way you judge the mother of all Moabites, because in a way, the story is very similar. Again, two young men have died, the husbands of the daughters of Lot and the husbands of Ruth and Orpah. There is a problem, there is no continuation of the family.

The elder woman is initiating, the mother of the Moabites. She is the one who initiates what they do. And Naomi is the one who initiates, who will meet Boaz. And we have also many words in the two stories that appear in both, for instance, shachov or to lie. Or of course, Lot is drinking and Boaz is drinking before Ruth meets him in the threshing floor, et cetera.

Another story that serves us very well is the story of Genesis 38. That’s a story of Judah and Tamar, because there too, what happens? Again, there is the husband of Tamar. Actually, two sons of Judah have died. Again, there is no continuation of the family. A woman, Tamar, is initiating how to solve the problem. And the plan works very well. The plan works, but not with the man she planned on having a son with, because Tamar wanted to be married to Judah’s third son. But at the end, she slept with Judah.

And here too, the ideal would have been to get married for Ruth, to get married to the goel [redeemer], the closest relative. At the end, she marries Boaz. So you see the resemblance.

But again, you see that Ruth is much superior to Tamar. Tamar is not behaving that well, she disguises herself as a prostitute. She slept with Judah. He has no idea whom he’s sleeping with. And Ruth doesn’t initiate anything. It was Naomi who sent her to the field of Boaz. And anyway, they don’t sleep together that night. Some people think that they sleep there that night. No, he’s telling her, no, let’s wait for the morning and go to the gate and do everything according to the law.

And then they get married, and God is very happy at the end with the marriage of these two. As it’s written there, “And God gave her pregnancy.” So we have the approval of God.

Now, the story of Genesis 38 is an anti-Judaite story. It’s a Josephite story against Judah, who married a Canaanite woman and then he becomes a widower, and the moment he sees a prostitute, he jumps and does what he does.

So if the people of Judah — now I’m getting back to the Second Temple period — if the people of Judah say, well, we don’t like Moabite women… Shh. Look at yourselves. Look at your history. You are not better than the Moabite women. So you see how all these Genesis story stories are serving us in order to build the idea that we should not blame Ruth for anything that happened in the past, she is perfect.

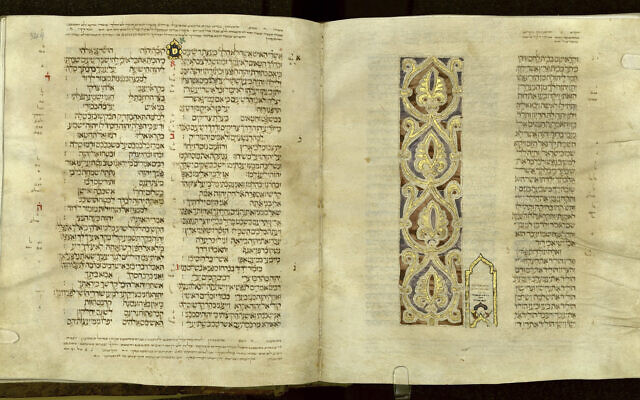

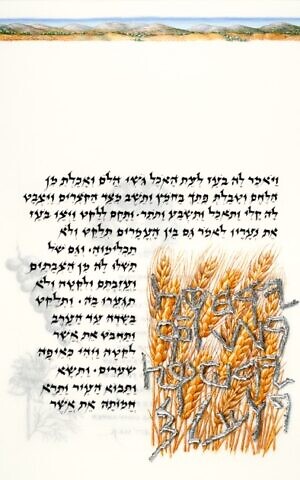

Now after seeing all these stories and we still have a problem, because now we are going to deal with a law, with halacha. How can we change the halacha? Look, in the Torah, we have two laws. One, in the Book of Leviticus, Chapter 19, “When you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap all the way to the edges of your field or gather the gleanings of your harvest. You shall not pick your vineyard…”

And we have another law in Deuteronomy 24:19, “When you reap the harvest in your field and overlook a sheaf in the field, do not turn back to get it. It shall go to a stranger…”

What the Book of Ruth is doing is combining these two laws. Boaz knows these two laws and combines there in order to take good care of Ruth. What we see here is that Boaz is not only letting her glean in his field, but he’s also telling his people, “Pretend to forget, pretend to leave some sheaves, pretend to so she won’t feel bad that she is gleaning.”

He’s protecting her honor and dignity.

Exactly. But the fact that he’s combining two laws shows you that it’s not the dry law that matters. It’s the spirit of the law that matters. If you understand that the spirit of the law is taking care of people, then you are ready to be flexible.

And then we get, of course, to the main problem, or another main halachic problem. We all know the story of the Law of the levirate marriage, yibum, in Deuteronomy. Ruth doesn’t fit into this law.

There are no more sons for Naomi.

There are no more sons and already in the first chapter, Naomi is telling her, I don’t have other sons for you. So it doesn’t work. On the other hand, we do have in the Book of Leviticus, chapter 25, if your kinsman is “in a strait and has to sell part of his holding, the nearest redeemer shall come and redeem what his kinsman has sold.” We have a law about redeeming a field, but we don’t have a law about redeeming a woman.

What the author of Ruth is doing is combining the two, combining the law of redeeming a woman and the law of levirate marriage and creating something new. It’s a halachic midrash! Again, we want to solve Ruth’s problem. The dry law does not allow it. Well, should remind you of our times when the halacha is so rigid, so dry, you cannot change anything. And here you see being creative, being able to combine two laws and to create something new, solves the problem of Ruth.

It sounds like you feel like this is a case of compassion, and perhaps it is. I also just wonder, did they perhaps consider Ruth property?

I would not use this term for Ruth being property. But anyway, what matters here is that we want to solve the problem of this woman, of this family. That’s what matters.

Do you have in your head who this author could have been? What was this person? What world did he come from?

He was, I would, say that he was something between a Conservative and a Reform Jew or perhaps a very modern Orthodox.

Or a rebel Cohen.

Something like that. A man that understood that one has to solve the problem of all these Moabite and Ammonite and foreign women, because when you read Ezra and Nehemiah, they are demanded to divorce these women. These women have families, they have children. So one had to come up with a solution. And now we get to the most difficult part.

The most difficult part is, of course, still we have this law in Deuteronomy — no Ammonite or Moabite women — and what can we do? But, the law in Hebrew, “A male should not…” A “male,” so perhaps this law is only about males and not about females, so we can actually allow Moabite and Ammonite women to get married to Jews. Fantastic.

It’s a very dangerous way of interpreting because according to this law, you can murder me now.

Because I’m a female, I get a pass.

Exactly, you get a pass, and I’ll be dead. [Laughs] And, you see that the Book of Ruth has changed the halacha because in the Mishnah in Tractate Yevamot, we read, “The male Ammonite and Moabite are prohibited, and the prohibition concerning them is forever, but the women are permitted forthwith.”

Okay, so many questions here. You’re depicting this author as basically a halacha maker, right? And so during this period in which the book you suggest is written, do we have any other authors who are doing the same thing? Any other texts that are showing us that people can be creative, that are building their own midrash in Scripture?

Look, the midrash in Scripture starts when the first letter in the Bible has been written, because the writers are changing the oral traditions so they go well with their ideology, their religion. The Bible is all about midrash. Midrash does not start with the rabbis. Midrash can be found within the Bible itself. And when we get to halachic midrash, if you look at different laws, for instance, take the law of the Hebrew slave. You have the law of the Hebrew slave in Exodus 21, and then again in Leviticus 25, and then again in Deuteronomy, chapter 16. Different laws. But you already see that if you read these laws closely, you can see there are different stages. The law of Deuteronomy is actually interpreting the law of Exodus, but then some additions have been put into the law in Exodus, so it goes well with the law in Deuteronomy. That’s what they call the boomerang effect.

You need to smooth everything out — the editors, I mean.

Because otherwise you have a problem. Okay, I’m going now to the market to acquire a Hebrew slave. Am I going to treat him according to Exodus or Deuteronomy or Leviticus? Of course you have at the end, you have to create one way of interpreting these laws, and the process starts already within the Bible.

It’s basically time travel paradoxes that they have to sort out throughout the tradition. But I want to take it back to this time period and this civilization that we’re talking about, that’s reading it or at least hearing the stories. You’re talking about somebody who is incredibly literate in the Torah, at least.

By the way, he’s literate in the whole Bible, because there are quotations even from Chronicles, the Book of Job. Just think about it, Naomi is like a female Job, right?

For sure.

He knows almost the whole Bible. And that’s another proof that it’s a very late book.

Right. And then I wonder if it’s received in a way in which it’s written — as an opposition text — and so therefore, it’s not included in the chronology that the author intended?

No, that’s not the reason. It’s not included there because this part of the Bible has already been canonized. That’s why it’s only in the Ketuvim [Writings].

Okay, so we have no idea how it was received by the people who heard it for the first time?

No, we don’t know how it was received by the people who heard it the first time, but then we see that a) it was accepted into the Bible, and b) it changed the halacha. The author was very successful, for sure.

And today, when we’re reading it, we’re getting, I mean, obviously when you read any text, you’re reading it from your own perspective. But I wonder if people are receiving the message that you’re finding there — that halacha can be creative.

I hope that people do get it. If not, I’m there to help them.

It’s such a pleasure hearing about this book of Ruth from your perspective. And I wonder just before we end up, let’s talk very briefly about the importance of biblical literacy in contemporary society. You can see in the secular Israeli school system that the Bible is not necessarily being reinforced. And I imagine in the more Orthodox systems, the ultra-Orthodox systems, the Talmud takes precedence. Where do we put the Bible today in Israeli literacy?

It’s very painful. I really mourn the situation that people now, or in at least secular people, don’t know their Bible anymore. Very different from the time, long time ago, when I was a young boy, when we learned the Bible. And there are many reasons. Let me try to mention some of the reasons the Bible is not as popular as it used to be. First of all, the language, the Hebrew language, changed a lot. For Israeli kids nowadays, the Bible is written in a foreign language. Biblical Hebrew is very different from modern Hebrew, and modern Hebrew is so very poor, or at least the way it’s being spoken nowadays by young people, it’s very poor.

Would you put it at the level of Shakespeare for a modern English speaker? That different?

Oh, definitely. So that’s one problem.

The second problem is that since certain parts of the society demand a monopoly on the Bible, take, for instance, the settlers, they demand that their interpretation of the Bible is the right interpretation. They know what God meant when he said whatever he said. So if you demand a monopoly, okay, take it, go away. We are not going to deal with it anymore. And that’s a terrible mistake of the secular people. It’s ours as much as it’s theirs. The fact that they demand a monopoly should not let us give it up. So I hope that one day we’ll find a way to bring it back to the secular people.

Something else. We don’t have enough good teachers of Bible. There is a great shortage of teachers. So in many schools, I hear that if there is nobody to teach the Bible, the sports teacher can go into the class and teach the Bible. Because we all understand the Bible. You need teachers who deeply understand the text.

So tell us about the Revivim project.

Revivim was our way to start a revolution, to change the situation. And it works very well, but it’s not enough nowadays. Every year we have in Revivim about 12 or 13 people only. We should have had 50 people there in Revivim.

But humanities in general is suffering.

That’s another reason why the knowledge of the Bible is so poor. Because humanities in general are not very popular nowadays. When I was a student of Bible at this university, there were 300 students in the department of Bible. Now I don’t think that there are even 100. And that’s another reason.

When I was young — oh my God, I was young once! When I was young, Bible went very well with Zionism. It was the time of David Ben-Gurion who was the prime minister of Israel, and for him, the Bible meant a lot. Here we are, returning to the land of our fathers. Here we are, speaking the language of the prophets again. Here we believe in the values of the prophets again. Here we cultivate the land, the way it was cultivated by our patriarchs, et cetera. And that’s how we took it. That’s how we understood it. Because for us, the establishment of the State of Israel was a miracle. Now, people who are born nowadays take it for granted. We live. The land of Israel is now like any other country in the world.

So the stories of the Bible or the Bible, in general, don’t speak to them the way it spoke to us. But we should not give up. We should try, again and again, different words to cope with this problem. And I see some hope.

If I think now about all these demonstrations now, at some point we gave up. We secular people. I’m one of them.

I am as well.

At one point we gave up the flag. Now you see that all these secular people are standing, demonstrating, holding the flag of Israel in their hands. We demand back what was taken from us, that we gave away to others. And I think that the very same thing, slowly, slowly will happen also with the Bible. Now that we are in the mood of fighting the Haredim, we’ll take back what they or others have taken from us.

We can see it in the youth. Several of my children are now at the stage of mechina, and most of these, between high school and army programs are all about Jewish identity, all about learning.

Right, so there is some hope.

There’s a lot of hope.

Okay, I’m going with you. A lot of hope.

Excellent. Yair, thank you so much.

You’re very welcome.

What Matters Now podcasts are available for download on iTunes, TuneIn, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, PlayerFM or wherever you get your podcasts.

Check out last week’s What Matters Now:

There's no paywall on The Times of Israel, but the journalism we do is costly. As an independent news organization, we are in no way influenced by political or business interests. We rely on readers like you to support our fact-based coverage of Israel and the Jewish world. If you appreciate the integrity of this type of journalism, please join the ToI Community.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel