What Matters Now to historian Sara Hirschhorn: Extremism is now mainstream

For an American scholar of Israel’s ultranationalistic movements, a research trip that coincides with the Jerusalem flashpoint Flag March couldn’t have been better timed

Welcome to What Matters Now, a weekly podcast exploration into one key issue shaping Israel and the Jewish World — right now.

On Thursday this week, tens of thousands of marchers — including several government ministers and MKs — marked the 1967 reunification of Jerusalem under Israeli sovereignty with participation in the annual Flag March.

While most of the masses sang, danced, and yes, caused a ruckus through the Old City’s Muslim Quarter, much like every year in the recent past, at times parts of the mostly under-30, largely male crowd acted like a tinderbox eager for a spark.

What was different this year is a group of left-wing activists blocked a main artery from the West Bank bloc of Gush Etzion to prevent marchers from reaching the capital. Perhaps taking a page out of the judicial overhaul protests, they stood with massive banners, chanting, “Fascism will not pass; the marchers will not pass.”

This push-pull political situation in Israel is the stuff scholars of contemporary history dream of. And for Dr. Sara Hirschhorn, an American historian and public intellectual who focuses on the Israeli ultranationalist movement, a research visit to the Holy Land couldn’t have been better timed.

Hirschhorn is currently an inaugural fellow at the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) Center for Antisemitism Research and an instructor in Jewish and Israel Studies at Rutgers University. In addition to her research into Israeli extremism, she also focuses on Diaspora-Israel relations and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Her first, award-winning book, “City on a Hilltop: American Jews and the Israeli Settler Movement” (Harvard, 2017) will soon be followed up on with an in-progress manuscript entitled “New Day in Babylon and Jerusalem: Zionism, Jewish Power, and Identity Politics Since 1967.”

We sat together this week and in our wide-ranging conversation, we discuss the increasing extremist symbolism of the Jerusalem Day Flag March. We also drill down on how Israel’s far-right parties are now considered mainstream as part of the Knesset coalition.

And, we discuss how by simply envisioning what the world could look like the day after peace breaks out, we may actually get there.

This week we ask Dr. Sara Hirschhorn, What Matters Now.

The following transcript has been lightly edited.

The Times of Israel: Sara, thank you so much for joining me today in the Nomi Studios, our partner podcast Israel Story’s studios.

Sara Hirschhorn: Thank you for having me.

Such a pleasure to see you in person after so long that you haven’t been able to come to Israel, and I’m very, very pleased to have this conversation with you today. We are facing on Thursday one of the more controversial days of the year, and I’m talking about Jerusalem Day’s celebrations of the March of the Flags. So I ask you, Sara, in this week of controversy and conflict, what matters now?

I think what matters now is what’s going to happen on Yom Yerushalayim (Jerusalem Day) on Thursday, which will affect not only domestic politics and the precarious coalition that Netanyahu has assembled and needs to keep intact in order to pass his budget by the end of the month, but also a very possible escalation that will affect local, regional and international geopolitics.

As listeners can hear, we are recording a couple of days ahead of Jerusalem Day, but all signs are go. It’s very, very likely that this march will happen and be protected by over 2,000 police and security members. Of course, we need to remind our audience that the National Security Minister is none other than Itamar Ben Gvir, who himself has said that he will take part in this controversial day. What, first of all, makes this day so controversial?

Well, I think this day has become more and more controversial over time. Jerusalem Day began in 1968, the first year after the “reunification” of Jerusalem, and used to be a much more pluralistic and widespread phenomenon amongst Israelis of all stripes and stars, we could say. Religious and secular, from Ashkenazi and Mizrahi backgrounds, and many other groups that participated for decades and decades.

In recent years, the march, particularly the march through the Muslim Quarter of the Old City, has become increasingly fraught and controversial. And the participation of ultra-nationalist activists, some of which of course, have now become members of Knesset, like Itamar Ben Gvir, have made the day much more political than religious and have certainly changed the tenor of the whole celebration.

Of course, the participation of Itamar Ben Gvir in 2021, alongside some of his other activities in east Jerusalem, certainly heightened tensions and led to a significant escalation, one that I fear might re-trigger the end of this ceasefire that just took place only a few days ago.

Right. As you mentioned, the 2021 march led to an 11-day conflict with Hamas. But do you actually really have great concerns that it will re-spark the violence?

I think so, because if I ask an average Israeli what they think of Jerusalem Day, they might imagine themselves waving flags in Gan Sacher, a major park in Jerusalem, and having barbecues and celebrating the spirit of living in Jerusalem. But if I asked anybody on social media what their image of Jerusalem Day is, it’s that famous photo from 2021 that looked like a bunch of ultra-nationalist youth activists dancing in front of the Kotel (Western Wall) with the Al-Aqsa Mosque burning behind it. Now, we know, of course, that that was kind of a false flag, that that wasn’t the Al-Aqsa Mosque on fire. That was a tree that had caught flame, and it just appeared that way in the photo. But certainly, I think if you ask anybody on social media, what is Jerusalem Day to them? It’s that image.

I think it’s that image also for people who live here in Jerusalem in many respects. It’s no longer, I believe, this happy day of celebration. It has instead been, I don’t know, co-opted by the National Religious Party. So let’s talk about this cooption and when did that actually begin?

Well, I think it began a bit earlier than the appearance of Itamar Ben Gvir in 2021. It’s been going on over the last decade, not only on Jerusalem Day, but on other holy days or other days of national celebration. And just generally, the presence of activist youth in the streets of Jerusalem has escalated over the last several years, and sometimes there’s been clashes with police or with other peace activists. So this isn’t necessarily new.

But I think that Jerusalem Day, because of its significance to the religious Zionist community, has become a kind of focus of attention. And the parade of the flags that’s marched through the Old City has become kind of a convenient symbol to organize sympathizers to this message.

Let’s describe the march a little bit more. There are tens of thousands of mostly youth, mostly national religious. It’s somewhat sex-segregated, and it’s, in a way, an excuse for youth to behave badly. Explain a little bit more what I mean.

So I’m going to agree with you. I’ve actually never been myself, at least to the part that marches through the Old City because I don’t necessarily feel that it’s a particularly female or gender-neutral space. It’s very much an activity that not only is very political but also seems quite macho and kind of the toxic masculinity of Jewish power is also an element of this whole flag parade. And as you said, it’s also a lot of really young people, which is true of a lot of these ultra-nationalist groups, people who both live in the settlements but also within territorial Israel that are gravitating towards these groups because they have charismatic leaders and because it’s a place to hang out. Especially if your home life isn’t as stable or as happy as one might hope. And I think that some of the people who participate aren’t even necessarily attracted to the march or to these groups because of ideology, but because of social and demographic reasons.

The march is not necessarily a “bad thing.” I don’t want people to get the wrong impression. What we’re trying to drill down on here is the repercussions of the cooption of it and the ramifications and the ripples of — let’s just say it outright — racism that goes through the march, at least in clips that I’ve seen and in talking with people who have been to several of these marches.

I think it’s very intimidating, particularly to members of the Jerusalem community that live in the Muslim Quarter or other parts of the Old City who are not Jewish and don’t necessarily look upon the reunification of Jerusalem or the capture of the City of Jerusalem in the 1967 war in the same way that the Jewish community who lives in the City of Jerusalem may feel. And also I think that over the years it’s become less of a pluralistic holiday for many other streams of Judaism who want to participate in this. I’ve now seen, just anecdotally on the Internet, that there’s lots of other alternative activities for people who want to celebrate Jerusalem Day and feel really deep religious and political significance to this moment and want to reclaim it for themselves in a way that seems a little bit more open and diverse.

But the march itself, I think, has become much more narrow and even we might say fringe, although what used to be fringe is now in the Knesset. So it’s hard to describe it that way. But I don’t feel that the march itself has become or is the same kind of activity that once was.

On the other hand, we do see some other groups that are really trying to reinforce a different kind of message, particularly Tag Meir, which is a riff on the word Tag Mechir “price tag” operation. They are calling it a kind of brightening or I guess, more inclusive kind of movement. And they often go to the parade or alongside the parade and hand out flowers and candy to residents of the Old City to try and reinforce the message that this is a city for everyone, even if the political idea of the unification of Jerusalem is very controversial.

So I think there are opportunities to try to take back the streets in a way from what the parade has become. But I think it’s less and less of what it used to be 50 years ago, which was just a mass celebration of the City of Jerusalem and access to the Old City, which of course, was at that time new and novel for the Jewish community in Jerusalem.

Let’s talk about what you just alluded to that the fringe politicians have now become major players in the Knesset, and I would argue that this in a way started happening quite a while ago, even with former prime minister Naftali Bennett perhaps even prior to that. So how did these settler leaders become such major forces in Israeli politics?

Well, it’s a long transition. Of course, this starts back in the 1970s when the Mafdal or the National Religious party became part of the governing coalition for the first time. With the election of Menachem Begin and the rise of the right in Israel, which basically changed the political map from a very Ashkenazi, socialist, Zionist-focused Zionism of the 1948 to 1977 period. And the Mafadal, which of course at that time was a party of religious Zionists who were just beginning to see the impact of the Israeli settler movement in 1977, and began to kind of grow some of their ideas now that they were in power.

But I think things changed significantly in the decade of the 1990s with opposition to the Oslo peace process, which brought some figures to the national stage. We might remember that even Itamar Ben Gvir himself was a youth activist in those days, was out in the streets of Jerusalem crusading against the Oslo Accords and kind of cut his teeth in those years. And we can point to many other figures who have a kind of similar trajectory. And certainly in the last several years, with the decline of the peace process and the almost exclusive reign of Benjamin Netanyahu, I think that actually, ironically, has given room on the right for other figures to appear to Netanyahu’s right to try to steal the thunder a bit from his presence as the staunch Mr. Security image, because there really hasn’t been any other prime minister than most young people in Israel know, and I think many settler leaders feel it’s time for them to get their due and also to stand in opposition to some of Netanyahu’s politics.

Before we talk about Itamar Ben Gvir and Bezalel Smotritch, who also must be mentioned, let’s talk a little bit more about the image of Naftali Bennett, who was, we should remind people, was the leader of Yesha, of the settler umbrella organization.

So Naftali Bennett actually has a really interesting biography for someone who became a settler leader, just like we might consider Theodor Herzl as being like an unlikely forerunner of modern Zionism. I think we can also see Naftali Bennett in the same way as being kind of an unlikely forefather of the Mafdal or the new reincarnation of the National Religious Party, because he himself came from a Diaspora background.

His parents are American Jews who moved to Israel from California. He speaks English fluently. He wasn’t necessarily entirely raised solely in the Israeli tradition. He has other roots in other places, and his “cred” on religious lifestyle issues, I think, at the time, and still even today, is a little thin. He wears a very small kipa. His strict observance of religious practice, I think, is perhaps in question. And he lives in Raanana. He doesn’t live out in the settlements, and he comes from a business background. He’s a multimillionaire, maybe, possibly gazillionaire, who really cut his teeth in the high-tech movement and not as a youth activist in Oslo or any of the other places that we might see settler leaders coming about. But I think he has from his professional life has a great deal of organizational savvy and is a good networker, and has also shown, I think even in the last government, a great ability to be a leader and to work across the aisle, as we might say in the United States while still retaining the integrity of his beliefs. Now, we might not agree with his beliefs, but I think that he was able to do both in the last government.

So he’s considered a traitor by many of the current settler movement because of course he made a coalition with an Islamic party, Ra’am, and not only because of that, I think. I think he also portrays a different persona than the settler movement is currently looking for, which led to a vacuum, which led to the rise of the Religious Zionism Party and also Otzma Yehudit. Let’s talk first about religious Zionism, Bezalel Smotrich and what does he signify? He was of course the founder of Regavim. So talk about Regavim to begin with.

So first I just want to say that I think Naftali Bennett kind of got a little bit of a bad rap here. I don’t think that he necessarily sold out his ideals, but he was perceived as selling out his ideas by forming this broad-based coalition. So we don’t know what he might have done had he stayed in power, but certainly his actions were seen as a betrayal of the movement’s ideals and of Greater Israel and ultra-nationalist values. So he of course now is out of politics and other people like Itamar Ben Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich who are seen to be more of the party faithful, are seen to be those who can be relied upon to push forward this agenda.

So Bezalel Smotrich is still a relatively young man [43], so he’s done quite a lot in his very short career. But one of the things that he was very actively involved in is an NGO called Regavim, which straddles kind of the political and legal vanguard of the Israeli settler movement. No longer the kind of old school, Yesha council approach of having an umbrella organization of settlements and different regional and municipal councils that will govern these affairs, but a kind of think tank/activist platform that is going to try and shake up the old way of doing things.

And they were able, I think, to insert a lot of policy ideas and platforms into the government and into the legal process regarding the settlements, and could kind of be seen alongside the Kohelet forum as being another real force in Israel, although one that maybe is a little bit more homegrown than Kohelet, which has roots and donors in the United States. Regavim is much more local and young and is definitely working very hard on the ground to transform the map in the West Bank.

So let’s talk about Itamar Ben Gvir and to me, he kind of seems like filling the space of the “disruptor.” Do you agree with that?

I think he is. I think also his background is very different from Bezalel Smotrich. He comes from a Tunisian immigrant background. He’s Mizrahi. He hasn’t necessarily had some of the, I guess, privileges of growing up within the elite that Bezalel Smotrich and some of his colleagues in Regavim have. So he comes sort of as a disruptor or an outsider.

He may be a kind of maverick character in Israeli politics, but he also is able to organize a lot of younger disaffected, particularly Mizrahi voters and some now hardal voters, people who are sort of on the fringe between the haredi or ultra-Orthodox world and the national religious world who really haven’t had a space for themselves in traditional national religious Zionism settler politics, which has also been heavily dominated by an Ashkenazi elite. People who sort of resemble the Bezalel Smotriches of the world. And this is a new opportunity for people who have a different ethnic and social background to be involved in politics. And I think Ben Gvir has really inserted himself very forcefully in that way. Of course, we don’t need to talk about his very controversial trajectory to getting to that position.

He didn’t serve in the IDF. He was convicted on terrorism charges. He obviously was a youth activist and a major, you know, a major figure known as kind of a troublemaker, you know, throughout his youth. But that has certainly appealed to a lot of a lot of Israelis who see themselves on the sidelines too and want to get into Knesset just like Itamar Ben Gvir has.

The bad boy image in a way. Before we move on, do drill down on Ben Gvir’s trajectory. You talked about him as this activist youth, but it’s more than that. He was a Kahane follower. Talk to us about this element.

So I think, as I had mentioned Itamar Ben Gvir is the son of Tunisian immigrants who grew up on the outskirts of Jerusalem, now in what is considered very gentrified real estate. But back in the day was a very, I think, kind of rough transition for many Mizrahi immigrants who arrived in Israel in the 1960s.

He grew up and was very much radicalized by movements that he associated himself with. He denies it today but is certain that he was a pretty proud Kahanist, a follower of Rabbi Meir Kahane, the ultra-nationalist xenophobic rabbi from the United States who immigrated to Israel in the 1970s and amongst other groups tried to mobilize young Mizrahi men to join his movement. He was a street protester. He was arrested any number of times on disturbances of the peace and terrorist charges and was convicted on, I believe, 11 of these counts, though don’t quote me on that. And he became a follower of other violent members in the movement. He famously had a poster of Baruch Goldstein, the perpetrator of the 1994 massacre at the Tomb of the Patriarchs Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron up on his wall until some journalist caught hold of it and he took it down for public relations reasons.

But he certainly was very deeply involved in that kind of politics in his youth. He did not serve in the army, which is the traditional trajectory of young Israeli men, because the IDF itself rejected him as a candidate, feeling that he was far too unstable to be given a gun on behalf of the State of Israel, given his background. He did go to university. He became a lawyer and spent the early years of his professional career defending clients who had been accused of settler terrorism. And then he transitioned from this kind of activist activities to becoming more involved in party politics and eventually kind of founding Otzma Yehudit and becoming a member of Knesset.

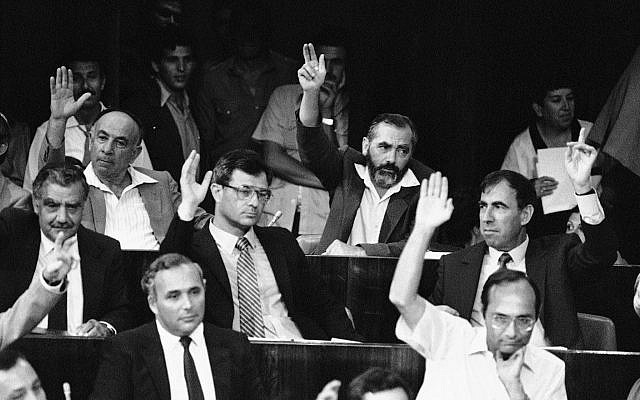

Now, Kahane himself was in the Knesset in his Kach Party, which was eventually barred from the Knesset for racism. Do you see that Itamar Ben Gvir has learned any lessons from his, shall we say, mentor?

Absolutely. I mean, Meir Kahane probably is the most important American immigrant to Israel since 1948. And I say that with great hesitancy because I can think of many more illustrious members of Israeli society who have contributed in other ways. But unfortunately, I think Kahane has had a profound impact on a whole generation of people.

Right around the time that Itamar Ben Gvir was born [1976], I guess Meir Kahane was making his first runs for Knesset in the late 1970s and then succeeding in getting into Knesset as the sole member of representing the Kach Party in 1984, and then eventually having his party banned under charges of racism and incitement to violence in 1988. But his reverberations, both in activist circles as well as the understanding that one could transition from activist politics to party politics, were really significant for a whole generation of ultra-nationalist youth. And also that Kahane organized largely amongst young men, particularly young Mizrahi men who found themselves disenfranchised from traditional, dare I say it, Ashkenazi party politics was also kind of a route to the Knesset for someone like Itamar Ben Gvir.

I have this theory that the 2005 Disengagement essentially reset the settler movement in many ways, and these “young” people that we’ve been discussing, Bezalel Smotrich, Itamar Ben Gvir and others are thinking in a different strategic mindset than the settler movement had prior to Disengagement and working in the system in a very different way. Would you agree?

I think so, although I think it goes beyond them and that sort of part of the ideological spectrum. I think everybody has had to rethink the whole idea of territorial disengagement because maybe it wasn’t foreseen or maybe it was. We still don’t know because the archives for these kinds of questions are not yet open and eventually historians and scholars will have a lot more information about what [former prime minister] Ariel Sharon envisioned and what they thought the likely outcome was going to be.

But we all know today that in 2006, Hamas took over the Gaza Strip and in addition to persecuting the Gazan people, has also been using the Gaza Strip as a launch pad for rockets against Israel. And I don’t know that the same calculations about territorial withdrawals can ever be made again in the same way, given what happened.

And that kind of sense of failure to achieve two states living side by side has completely reshaped the whole political process. Also, I think young activists saw their power in the Disengagement. They are able to mobilize people across the country, and the whole idea of “A Jew doesn’t raise a hand against another Jew,” the kind of bumper stickers that were seen across the country in 2005 and 2006, I think, has also scarred the Israeli public. Those images of brother against brother dragging people out of their homes in Gaza is the image of a civil war. That’s the nightmare of Israeli society.

I want to talk about this sense of betrayal a little bit more. In your previous book, you’re now working on a new book, but in your previous book “City on a Hilltop: American Jews and the Israeli Settler Movement,” you talked about the idea of the settler as the new pioneer. And during the Disengagement, these people were physically dragged from their homes. Many of them were children who are now in the political sphere, and they saw this huge failure of the Israel that they loved. That the land of Israel that they were raised to devote their whole lives to, turning on them and just crashing their lives down. Don’t you think that this is more of a driving force than the fact that Hamas is in Gaza?

I think that the messaging on all levels was terrible. There was no real game plan for what happens the day after the withdrawal, or at least if there was, we don’t exactly understand how it came to be that Hamas has now been in charge and obviously has not turned out to be a peaceful neighbor to Israel. But certainly, I think any disengagement that happens in the future cannot be modeled on that of Gaza.

Not only was it the image of people being dragged out of their homes physically and the portrayal of ideals that these are the new Zionist pioneers post-1967, it’s also, I think, the sense that those who were taken out of their homes, there was no game plan for them in the weeks and months and years ahead. And they remained underserved and disaffected and angry and ready to mobilize against the state. And it creates, I think, a very dangerous element within society that feels entirely, entirely forsaken.

And if you imagine that on a mass scale in the West Bank, it’s almost impossible to understand not only how this would benefit the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Like, how would that actually take place on a much larger scale than in Gaza, which was only 8,000 people, which maybe isn’t a lot, but maybe is a lot, but isn’t the same scale as the West Bank, but also, how could Israeli society survive another Disengagement on a very large scale?

And so now we’re faced with a coalition that is doing its utmost to make sure that there will never be another disengagement as was, and maybe as could have been, had it been planned a little better. And do you think that they will have this ripple effect in the future and make it so that there will never be any hope for a Palestinian state?

Well, I mean, I think it’s dependent on what the international community is going to envision as the territory of a future Palestinian state. Even if every single settler stayed in their home, which was basically what was envisioned under the Trump peace plan, that would create a Palestinian state on, say, 40% of the West Bank. There are microstates that exist in the world, but would that satisfy the Palestinian people? I highly doubt it. So I think it’s really going to depend on what, you know, the compromise between the ideal and the real.

I do think that the settlement bloc concept is still functional for the most part, with very worrying exceptions, particularly in the Jerusalem area. So I don’t think the entire rubric of Oslo has been destroyed. But it’s not only what’s happening on the ground, it’s what’s happening in people’s minds. Will they tolerate another disengagement of some scale in exchange for peace? And what will that peace look like? Because if it looks like what people thought it was going to look like in Gaza, I think it’s a non-starter.

You talk about the idea of envisioning the peace of the day after, the day after disengagement, the day after a ceasefire, the day after Peace has broke out. How do you see that?

Well, I’m really worried when I hear people on the left, right and center saying, what does it look like the day after the occupation ends? And, you know, you’ll hear this refrain, you know, from groups on the left, but also from groups on the right that want essentially the occupation to continue. And I don’t think anybody has really done enough thinking to know what that looks like.

What is Palestinian civil society capable of in those moments? Could any settlers remain in their midst? Even ironically, Rashida Talib mentioned about Nakba Day that she also feels some hesitation about settlers leaving their own home, seeing the Palestinian experience in 1948.

What will the international community be willing to support and possibly even fund? I think there are a lot of open questions, but it’s one thing to bang the drum and say, this is the policy that should happen, but it’s another thing to try to enforce that without having any understanding of what the day after looks like. So if you want to say, let’s end the occupation, fine, but have a plan for what’s going to happen after that, because that’s a very dangerous and unstable moment that doesn’t justify perpetuating patterns and policies that have been in existence since 1967, but I do think that some thinking needs to be done about what exactly it looks like the day after peace emerges.

There are going to be a lot of betrayed people on all sides who no longer have an understanding of their world. Their whole universe will change overnight, and it’s very hard for human beings to catch up to that. So I think we need to be preparing the groundwork for that, not just from military, economic and defense perspectives, but also from a human perspective about how to prepare people in civil society, individuals and groups for that major transition.

It’s a transition that so many in Israel don’t think will ever happen. And we are, as you said, in this stalemate situation where the occupation continues and it just doesn’t seem like there’s any readiness, willingness or desire.

Well, maybe if people could dream about what that would look like, maybe that would help people begin to think about it. I’m not saying that they will necessarily shift ideologically, but maybe they might have more empathy for the situation and what needs to change in the future. But of course, Israel or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict isn’t the only conflict around the world that’s had to grapple with these questions. And not all of them have been so successful in other places either. It’s a very difficult process and one that’s very unstable.

Give us an example of a success story.

Well, I think the success story that everybody’s pointing to in the news right now is Northern Ireland, which commemorated the 25th year of the peace in Northern Ireland only about a month ago, right around the time that people were starting to worry about rockets shooting off again here. The television was full of pictures of a successful, or quote unquote “successful” peace process in Northern Ireland. But I think there’s a lot simmering under the surface there. Tensions that have not resolved, the rearming of militant groups, the remaining isolation between different religious and ethnic factions, that it’s kind of a cold peace in a way, which may be better than no peace. But I think we need to look around the world to other examples to help us envision what the future here might look like and maybe begin to dream a little bit, but with modest expectations.

As we mentioned, you’re working on a new book. Can you give us a little preview of what the idea is?

I’m thrilled to be here finally after three years away from Israel, and I’m resuming the research on a new book project that’s called “New Day in Babylon and Jerusalem: Zionism, Jewish Power and Identity Politics Since 1967,” which is a real mouthful, but it’s essentially a way of looking at the decades in the 1960s and 1970s as the first iteration of a lot of the contemporary debates we’re having about Zionism and progressive politics, Zionism and identity politics, Black-Jewish relations, and how, essentially, it’s becoming increasingly incompatible for a young Zionist, maybe on college campus, people that I work with all the time to both invest in their Zionist and Jewish identities, as well as be comfortable and productive in a lot of identity politics spaces. And how did we get to that point? And I think we can find the answers to some of those questions 50 years ago and maybe try to remind my readers of how these debates played out the first time, some paths not taken back in the 1960s and 70, where we might go from here, learning from the past.

Sara, thank you so much for joining me.

It was lovely to be here.

What Matters Now podcasts are available for download on iTunes, TuneIn, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, PlayerFM or wherever you get your podcasts.

Check out last week’s What Matters Now:

There's no paywall on The Times of Israel, but the journalism we do is costly. As an independent news organization, we are in no way influenced by political or business interests. We rely on readers like you to support our fact-based coverage of Israel and the Jewish world. If you appreciate the integrity of this type of journalism, please join the ToI Community.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel