What Matters Now to archaeologist Prof. Yonatan Adler: The origins of Judaism

Ariel University prof discusses his ‘excavation’ into the evidence for the practice of the Jewish religion – and points to when we know with certainty that Passover was observed

Welcome to What Matters Now, a weekly podcast exploration into one key issue shaping Israel and the Jewish World — except this week.

Ahead of Passover, as some Jews all over the world change sets of dishes, blowtorch their stoves and, of course, cover every last counter and corner with aluminum foil, we wonder: when did the practice of this crazy religion get its start?

So I invited Ariel University’s head of the Institute of Archaeology Prof. Yonatan Adler to our Jerusalem office to speak about his new book, “The Origins of Judaism.”

In our lengthy conversation, we hear how he treats the origins of the practice of Judaism as an archaeological excavation, working backward in time to gather physical and textual proof of the observance of the laws and commandments charted out in the Torah. This is a topic that has engaged Adler for well over a decade — including his doctoral research for “The Archaeology of Purity” — and he continues to explore it through his Origins of Judaism Project.

Adler, who obtained rabbinical ordination through the Israeli chief rabbinate in 2001, treats this question through a scientific assemblage of data points collected throughout the centuries and the guiding archaeological principle that “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

While Adler hasn’t yet found evidence for foil-covered kitchen counters, at the end of our discussion he does speak about the earliest evidence for the observance of Passover, and that matters now.

The following transcript has been lightly edited.

The Times of Israel: Yonatan, thank you so much for joining me today in our Jerusalem office.

Yonatan Adler: Thank you for having me.

Such a pleasure. Generally, I ask people before we start diving into the topic at hand, what matters now? Because the podcast is generally all about current events. But today we are going to talk about “what mattered then.” We’re talking about, of course, your new book, “The Origins of Judaism.” So what mattered then, Yonatan?

Well, the question is when is then? The question that I pose in my book is when did Judaism begin? And we’ll have to speak about what we mean by Judaism. And when we speak about when did it begin, how do we go about looking into that? That’s the question that we’ll be talking about today.

For sure. And what I like about your book is you’re, of course, an archaeologist, and the book is, in a way, set up like an excavation. We’re going top-down like you have to do when you’re at a dig. You’re proving the earliest possible moment in which you have evidence for the practice of Judaism. We’re not finding it, of course, at Adam and Eve. Let’s have a bit of a spoiler: What is the first moment of physical evidence for the practice of Judaism?

Okay, so I guess we’ll start with the end, and then we’ll go move backwards from there. The bottom line is that the earliest evidence that I find is during the Hasmonean period, so around the middle of the second century, before the Common Era. We’re talking about 200 years before the destruction of the Second Temple. There’s no evidence of Jewish practices related to Torah observance prior to that. But maybe we’ll walk this back a little bit and get a bit more into detail.

For sure. We need to, of course, define some terms as well. Again, we’re talking about Judaism, which is the human practice of the idea of the Jewish religion, shall we say. It’s more of a sociological look. Is that fair to say?

Absolutely. Actually what I’m looking at here is the question of social history. I’m looking at the question of what people are actually doing. I’m not looking at the question of from when does the Torah exist? So we can have a Torah that exists for many centuries before the regular people, the common people, are actually practicing it. And my interest is very specifically not in the question of when the Torah was written, when the Torah came to be. My question is when did the ordinary people, the people you would meet on the street, the farmers, the craftsmen, the homemakers, the ordinary people, when did they come to know about the Torah and actually put it into practice in their daily lives?

One of the things that scholars already in the 19th century recognized was that when we look through the Hebrew Bible, the Tanach, we don’t seem to find people observing the laws of the Torah. We don’t find anyone, for example, fasting on Yom Kippur, on the Day of Atonement. We don’t find ordinary people keeping Shabbat. We find prophets that are railing against people not keeping Shabbat. We don’t find people that are actually keeping Shabbat.

We hear about King David building a palace. We never hear about him fixing mezuzot on his door posts. We never hear about any of the figures in the Hebrew Bible putting on tefillin or the dietary rules for that matter. We don’t hear about anyone abstaining from eating pig or seafood. These are things that we don’t find in the Hebrew Bible. And already from the 19th century, scholars of the Hebrew Bible have noticed that we don’t find this in the Hebrew Bible.

Their assumption was that this all began in the Persian period. We’re talking about the middle of the fifth century, before the Common Era. After the destruction of the First Temple, the Jews returned to Judea and established a new province of Yehud, where Jerusalem is rebuilt. A Temple is rebuilt. So this is the Second Temple, according to the stories that we find in the Hebrew Bible, books like Ezra and Nehemiah.

And the story that we find in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah is that there was a figure named Ezra that came from Babylonia, and he came to Jerusalem with a Torah of Moses. And he reads this Torah before the entire people. And the people are shocked to learn that there is such a Torah. And they find in the Torah laws, for example, to build sukkot on the holiday of Sukkot. And they go out and do it for the first time since the days of Joshua bin Nun.

The assumption of these scholars of the 19th century was that Judaism begins then. It begins during this Persian period, around the fifth century before the Common Era. And since then, we have large-scale observance of the laws of the Torah.

What I’m doing in my book is I’m asking, is it so? Is that really the case that we have observance of Judaism from this period of time and onward? Or perhaps not? What is the actual evidence that we have?

The physical evidence?

Physical evidence, meaning the material remains, such as archaeology, absolutely. And also textual evidence. In other words, things that people are writing about which might indicate that ordinary people are keeping the laws of the Torah.

Can you give me some examples of that? Are you talking about letters or other kinds of documents or monuments?

Let me maybe spell out the methodology of the book, and then we can get into a bit more detail. What I do, as you mentioned, I approach this like an archaeological dig. We start an archaeological dig, and we start at the surface level, modern. We start digging in the ground, and we start finding tuna cans and Coca-Cola bottles. And as we dig deeper, we find more and more ancient artifacts.

I’m doing the same thing here in the book. I start from a period of time when we know that there was Judaism, that ordinary people were keeping the laws of the Torah. And what I show throughout the book is that the first century of the Common Era was just such a time. So in the first century of the Common Era, we find lots of evidence that ordinary Jews were keeping the laws of the Torah. And then what I do is I go backward in time from the first century of the Common Era. I look at the first century before the Common Era, the second century before the Common Era, the third century before the Common Era, and so on and so forth, backward in time, looking for where the trail of evidence ends.

So just to give a little benchmark, the first century of the Common Era is, of course, when Jesus would have lived and when the [Second] Temple was destroyed, things of that nature. And then when you move backward, what are some other historical events that people would know about?

The first entry is obviously around the year zero when Jesus was thought to have been born. He was crucified around the year 30. The Temple of Jerusalem was destroyed in the year 70. In the first century before the Common Era, we have figures like Herod the Great who refurbished the Second Temple. This is towards the end of the first century before the Common Era. This is the time of Augustus, Julius Caesar, and so on and so forth.

And as we go back to the second century before the Common Era, this is the time of the Hasmonean Dynasty. This is the time of the Hasmonean revolt, the story of Hanukkah, of course.

And if we go back even more in time, we get to the third century before the Common Era. It’s a little bit hard to speak about events of Jewish history that we can think of, because this is a period of time which is kind of a black hole in Jewish history. We don’t have many sources which tell us very much about it. One event which stands out in my mind in the third century before the Common Era, supposedly, this is the time when the Torah was translated into Greek.

The Septuagint was produced in Egypt, right?

Right, in Alexandria. If we go back even further in time, the fourth century before the Common Era, this is the time of Alexander the Great. And we get to the fifth century before the Common Era. This is the time when this area of the world was controlled by the Persians.

So now we have a map, a good chronology, in our heads. And please continue.

What I find when I look at practice after practice, prohibition after prohibition, I find that in the first century of the common era, we have lots of evidence. In the first century before the Common Era, as well, we have evidence of many of the practices based on the laws of the Torah. When we get into the second century before the Common Era, we continue to find evidence — but nothing before that.

So around the middle of the second century before the Common Era is really the earliest evidence that we have for practice after practice, prohibition after prohibition that ordinary Judeans are keeping the laws of the Torah.

You’re talking about Judeans. So let’s define that term as well.

I use the term Judean because in scholarship there’s a bit of a debate about when we can start using the terms “Jews,” “Jewish” and so on and so forth. It’s a bit of a funny debate because it’s about an English word. The word Jews. Jewish. The ancient words that we have don’t distinguish between Jews and Judeans. So we have: In Hebrew, “Yehudim.” In Arabic, “yehuda.” In Greek “udae.” They’re all basically the same word.

And it’s important here to point out, to put on the table that we have evidence for this group of people that goes way back. We have evidence that goes into, I would say, the first half of the first millennium BCE. So for many hundreds of years. And I’m not looking at the question of when do Jews first appear on the stage of history? When do Judeans first appear on the stage of history? Because we have that for many hundreds of years before we have evidence that these Jews, these Judeans, were keeping the laws of the Torah. So I’m looking at the origins of Judaism. I’m looking at the origins of when are these people that have existed for many hundreds of years, when do they begin to keep the laws of the Torah?

It’s important to put that on the table that we can have Jews, Judeans, that don’t know the laws of the Torah and aren’t keeping it. One is not connected per se to the other. And again, what I’m looking at is, when do these Judeans begin to keep the laws of the Torah on a wide-scale basis?

So we’ll talk about all the evidence that we have. But as I was considering your book, I kept thinking about idols. And in the First Temple period, you see at many archaeological sites throughout Israel idols. Idols that have been smashed, perhaps intentionally? Based on biblical prohibitions? Or is that not something that you personally looked at for this study?

We have to understand that in the early days, right before we have wide-scale observance of Torah law, Judeans, Israelites as well, were polytheistic. So there was a central Judean god whose name is the Tetragrammaton. But Judeans and Israelites were worshiping other gods as well. This is something we find in the Hebrew Bible. We find the prophets railing against Judeans and Israelites worshiping foreign gods. So there clearly were people that thought that Judeans, Israelites should be worshipping one God. And obviously, we find that in the Torah as well. But one of the questions that I look at is when do we have the earliest evidence for wide-scale observance of that?

In terms of the actual evidence that we have, I have a chapter, for example, on figural art. We find in the second commandment of the Ten Commandments a prohibition against depicting humans or animals.

Graven images, right?

Graven images. In the first century of the Common Era that was understood to mean even secular artwork. Regular profane artwork. One is not to depict humans or animals. And we find archaeological evidence for this: Judeans are not depicting humans or animals in any of their artwork. We have lots of artwork from the first century of the Common Era. We have mosaic floors. We have funerary art on coffins and ossuaries — bone boxes. Burial caves. We have quite a bit of Judean art at this period of time.

And consistently, this art does not include humans or animals. We have geometric designs or floral designs. We almost never have humans or animals depicted. And this is true for the first century of the Common Era. It’s true for the first century before the Common Era. It’s true for the second century before the Common Era. Prior to this, we simply don’t have this.

One of the things which really stands out is the coins. Judeans were minting coins during quite a number of periods of time. We have Judean coins from the first century of the Common Era, never depicting humans or animals. The same is true of the first century before the Common Era. The second century before the Common Era, the earliest coins we have are from then are actually well-dated, around 132 BCE. The time of John Hyrcanus I, one of the Hasmonean rulers. And what really stands out with these coins is that normally we would assume that a coin would have the profile, the picture of the ruler. We have that on coins today. And that was the case in antiquity as well. Coins always had the portrait of the king.

On these Hasmonean coins, not only is the portrait of the king missing or the ruler, but we have what I would call a “textual portrait.” Which means that it has the name of the ruler, John Hyrcanus, the High Priest and the Council of the Judeans. It’s a lot of words to put on a small coin. And this takes the place of a graphic depiction. I think this really stands out. And to my mind, it makes the statement that we are not going to depict a human on our coins.

We don’t have this in any earlier period. In the earlier coins, coins that we have from the third century before the Common Era, from the fourth century before the Common era, on every single coin minted by Judeans, in Judea we have figural art. And in fact, some of these coins have not only figural art, but actually foreign gods. For example, Athena, the Greek goddess, the owl of Athena. There’s one coin that has the name of the Judean High Priest — “Yohanan Hakohen” it says in Hebrew — and in the middle of that coin is the owl of Athena.

Not only do we have not a lack of figural art, we actually have figural art and actually, foreign gods depicted. These are the artifactual finds that we find from these periods prior to the Hasmonean period.

That is so fascinating. A lot of people theorize at least that the mitzvot, that the commandments, are to separate Jews from other peoples. And are you seeing that in terms of the physical evidence that you have collected? Because it sounds like in the coin that you pointed out of Hyrcanus, he was being very davka, as we say in Hebrew, being very intentional, of saying, “No, I’m going to actually observe this commandment. And I am different. And I am the Torah-true Jew. And I’m the one you should be following because I’m your true leader,” etc. And so if you’re talking about the other commandments, the Jewish laws that you’re searching for evidence for, is any of that also so very intentional and very different from the other people who lived next to them?

Yes, absolutely. So we can talk about another example: purity laws. We have again, when we talk about the first century of the Common Era, we have a large amount of evidence that Judeans are keeping the purity laws. We have textual evidence, but we also have archaeological evidence.

For example, we have hundreds of stepped and plastered pools throughout the country, everywhere where there are Judeans living and these were clearly being used as immersion pools. Ritual immersion pools for purity purposes, what came to be known as mikvaot.

We also have, at this period of time, large-scale use of stone vessels, vessels made out of chalk. And these were being used by Judeans because they understood, according to the rules of Leviticus, that stone does not become impure. Pottery, according to Leviticus 11, if it becomes impure, you have to break it. But stone is not listed amongst the things that one has to either break or wash. And it was understood that stone, therefore, doesn’t become impure.

Judeans at this time, are making vessels out of stone and using them on a wide-scale basis. There’s a very clear distinction between Judean sites, where we find these immersion pools and these stone vessels, and non-Judean sites where we don’t find these finds.

Both of these phenomena begin, they first emerge in the second century before the Common Era, during the Hasmonean period. Prior to this time, there’s no evidence that Judeans are keeping these rules.

Let’s talk about the dietary laws, because that’s a big one. And I know you’re a data guy, and one of the things that archaeologists like to do when they’re excavating is to measure the proportion of, for example, pig bones to goat bones to fish bones and what kinds of fish and all of that kind of thing. And that dates back much prior to the Hasmonean times. People have often used them to say to draw conclusions on who lived where. What do you say about that?

Okay, excellent. I have a chapter on the dietary laws. First of all, a methodological point needs to be made: When we look at evidence of animal bones that we find in archaeological excavations, this tells us what people are eating and what people are not eating. There’s a difference, though, between people not eating something and there being a taboo against that food. I’ll give you an example from today. Okay? Do you eat meat? Are you a meat eater?

I do.

Okay, so if you go into a supermarket here in Israel, I think it’s certainly the same thing in the United States and in most places in Europe, as far as I know. And if you look for beef and chicken, you’ll find it. If you look for goat meat, I think you’ll have a hard time finding it. Have you ever seen goat meat in any supermarkets here in Israel?

Maybe at a butcher shop, but not a supermarket.

I haven’t seen it at a butcher shop either. I’ve never come across it. Now, people here in Israel and in the United States tend to not eat goat meat. I don’t think there’s a taboo against eating goat. I would have no problem eating goat. I think most people in the street wouldn’t have a problem, but you don’t come across it. And the reasons for that are probably economical, they’re probably ecological.

I don’t know, cultural?

I don’t think it’s so much cultural. I think for whatever reason, farmers aren’t raising goats for meat, and that’s just the way it is. But that doesn’t mean that people are abstaining from eating goat meat. There’s a taboo against eating puppies or eating cats, but there’s no taboo against eating goats.

And so again, going back to your question, the fact that we don’t find certain kinds of consumption of certain kinds of animals does not necessarily mean that there’s a taboo against that. There could be other reasons — economic, ecological, and so on and so forth — for why farmers decide to raise a certain animal or not.

What is the data? When we look in the first century of the Common Era, we don’t have pig bones at Judean sites. We do have them at non-Judean sites. Now, again, that is consistent with the idea that Judeans aren’t eating pig because of Torah law, but it’s not necessarily proof of it. What we do have at this time is texts which tell us that everyone knew that Judeans were abstaining from eating pig because of Torah law.

We have, for example, Roman authors that are telling jokes about the Judeans that they don’t eat pig. One of the jokes is told about King Herod. The joke — supposedly Augustus, emperor Augustus himself told this joke — that he would rather be Herod’s pig than his son because Herod’s pig, chances are that he’d live. But his son… Herod was a nasty guy and he killed all of his family members.

Now, a joke like that would have fallen flat if everyone who heard the joke didn’t know that Judeans were abstaining from eating pig because of the Torah. So clearly at this time, Judeans were keeping the laws of the Torah with regard to abstaining from eating pig.

In earlier periods of time, when we get to periods before the Hasmonean period, the picture becomes a bit more complex.

We have a lack of pig bones when we get into the Iron Age at sites in the highlands of Judea. We have pig bones in the northern highland sites, the Kingdom of Israel. We have pig bones in Philistine urban sites. We have a lack of pig bones in Philistine rural sites. In Canaanite sites going back even earlier, we have a lack of pig bones and at sites from the Bronze Age, when there was the late Bronze Age, when there was an Egyptian presence in the land, we have pig bones where there were Egyptians.

Clearly, farmers at different times, in different places were making decisions about whether to raise or not to raise pigs, probably for economic, ecological reasons, which have nothing to do with the Torah.

We have a lack of pig bones at Canaanite sites 1,000 years before anyone would have imagined a Torah existing. A lack of pig bones is not necessarily evidence that people are keeping the laws of the Torah. This is something that we have to be very careful about.

We have a whole bunch of different pieces that we’ve discussed so far, and let’s wrap it up into some kind of unifying theory. What are you getting across in the conclusion of your book?

The book is actually a very data-driven book. And the first six chapters are exactly as we described — the first century of the Common Era as the baseline, the benchmark. And then we go backward in time. And what that provides for us is, and you’ll excuse me for my Latin a terminus ante quem. And what that means is that at the earliest evidence we have, where the trail of evidence ends, that provides the terminus ante quem, the period of time when or before which Judaism must have emerged.

I’m trying to be very precise here in what the data provides and what the data does not provide. We know that lack of evidence is not evidence of absence or absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. What that means is the fact that we don’t have evidence for widescale Torah observance before the second century before the Common Era does not necessarily mean that Judaism began then. It could be that Jews were keeping the laws of the Torah on a wide-scale basis in earlier periods in the third century, the fourth century before the Common Era. But the evidence simply hasn’t survived.

What I do in the final chapter is look at contextual evidence from the period before our terminus ante quem. So I’m looking at the evidence surrounding this question to see what was going on with Judeans in these earlier periods. And what I find is that what’s commonly thought of as the beginning of Judaism in the Persian period, in the fifth century before the Common Era, not only do we not find evidence of wide cultural observance, we find negative evidence.

I already gave you examples of coins that have foreign gods depicted on them. We also have texts from places like Elephantine. Elephantine is an island in the Nile River in southern Egypt where there was a Judean colony that was living there. And they’ve left numerous texts, numerous documents which have survived because Egypt is a dry area, and papyri are able to survive in this area. And these documents paint a picture of a Judean society that knows nothing of the Torah and which is actually breaking lots of the laws that we find in the Torah.

For example, one thing that really stands out is that they built a temple to the Judean god in Egypt. We know, of course, that according to Deuteronomy, the temple is supposed to be in only one place, which was eventually understood to be Jerusalem. And in building a temple in Egypt, they are worshiping the Judean god, but they’re also worshiping other gods, or at least acknowledging other gods. They’re taking oaths to gods aside from the Judean god. They’re giving monies, they’re donating monies to other gods aside from the Judean god. They’re naming their children both by the name of God and other gods as well.

These people are clearly unaware of the existence of the Torah. They’re certainly not keeping the laws of the Torah. We find a similar situation in Babylonia at this time. We’re talking about the fifth century before the Common Era, of the time when scholars generally think that Judaism first emerged. We have all of this evidence of nonobservance.

One other thing I’ll throw out at this time in excavations in Jerusalem — you mentioned faunal evidence, animal bones — we find fish bones at this time of fish, species of fish which are prohibited in the Torah. So, for example, we have catfish and shark bones and cartilage which are found from the fifth century and fourth century before the Common Era. They’re prohibited in the Torah, but we find them in Jerusalem.

Not only do we not have evidence of observance, we have actually negative evidence, evidence of nonobservance, which would suggest to me that this period of time, the Persian period, is not the best period of time to be seeking the emergence of widescale observance of the Torah.

Moving forward in time, the next period after the conquest of Alexander the Great is the Early Hellenistic period. And following that, we have the Hasmonean Revolt and the Late Hellenistic period. I think both of these periods of time are much more likely periods when Judaism first emerged.

And towards the end of the book, I make the suggestion that perhaps it was in fact the Hasmoneans that were the ones to adopt the Torah as the law of the land. So again, the Torah very likely was around for many hundreds of years but wasn’t well known. It wasn’t something that the masses knew about necessarily. It was the Hasmoneans, perhaps, that are the ones that decided to adopt the Torah as the law of the land and to spread knowledge of the Torah, to spread the observance of the Torah from the second century before the Common Era and onward.

We don’t have evidence for this, that it was the Hasmoneans that did this. But what we do have evidence for is that the Hasmoneans did this with peoples that they conquered. We know, for example, that the Hasmoneans conquered the Idumeans in the south of the country. This was a non-Judean ethnic group that worshiped the god named Qos and the Hasmoneans conquered them around the year 112 BCE and enforced the laws of the Torah on the domains. We would today say that they forced conversion on the Idumeans. But what the sources tell us, we have textual sources which tell us this, Josephus and others, that tell us that the Hasmoneans forced them to circumcise and to keep the laws of the Torah. We know that after John Hyrcanus I, Judah Aristobulus I conquered a people in the north called the Iturians. And he did the same thing. He forced them to circumcise and to keep the laws of the Torah. This is a sort of modus operandi of the Hasmoneans that they’re enforcing the laws of the Torah on the peoples that they conquered.

I think it’s not too much of a stretch of the imagination to suggest that perhaps earlier Hasmoneans, let’s say, perhaps Simon or Jonathan or Judah Maccabee, perhaps did this very thing with the Judeans themselves and brought the laws of the Torah to the Judeans, enforced the laws of the Torah on the Judeans themselves. And with that we would have the emergence of what I would call “Judaism.”

Since we’re recording during the Passover vacation, I need to ask you, what is the evidence for that story?

Okay, good. Using our methodology, the first century of the Common Era, we have lots of evidence, not any archaeological evidence per se, but textual evidence that Judeans are keeping the Passover. They are abstaining from eating leaven products, and they are eating unleavened bread, they are eating the Pascal sacrifice, and so on and so forth.

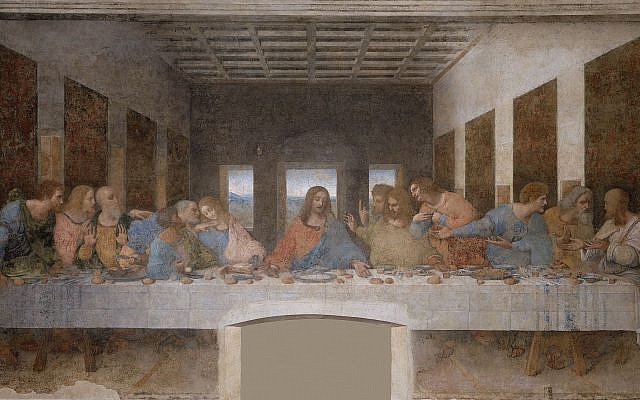

Just as an example, in the Gospels, we have a story about a famous Jew, Jesus, and his disciples who had a last supper, which, at least according to the Synoptic Gospels, was what we would call today the Seder, eating the Pascal lamb with unleavened bread, and so on and so forth. So we have this evidence from the first century of the Common Era.

We have some evidence from first century before the Common Era. Let’s say prior to this time, we do not have evidence that Judeans were keeping the Passover or the Festival of Unleavened Bread in any wide-scale manner.

Oftentimes scholars speak about a so-called Passover Papyrus from Elephantine, which we had mentioned — the island in the Nile River. And this papyrus supposedly speaks about Passover. It supposedly speaks about refraining from eating leaven products on Passover, and so on and so forth, hiding away leaven products in the house. It seems to be that the Judeans living in Elephantine, according to this papyrus, were keeping the laws of the Torah. And this papyrus is actually quite well-dated to 419 BCE.

Why do you keep using the word “supposedly,” though?

Okay, so why do I say supposedly? I said that the papyrus is the so-called Passover Papyrus. The problem is that more than half of the papyrus is missing and the papyrus has been reconstructed on the basis of what we find in the Torah. And it just so happens that all of the parts that talk about Passover are in the reconstructed parts.

So it’s fair enough that scholars will reconstruct a papyrus that is not well preserved on the basis of the Torah. Fair enough. We can try that exercise. The problem is we can’t then take that reconstruction and use that as evidence that the Torah was well known. Right? That’s called circular reasoning. We can’t do that.

So I say it’s the so-called Passover Papyrus, because once we remove all of the reconstructed parts of it, it no longer is talking about Passover.

Really fascinating. Thank you so much for all of this. Much food for thought, even kosher food for thought.

Thanks for having me.

What Matters Now podcasts are available for download on iTunes, TuneIn, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, PlayerFM or wherever you get your podcasts.

Check out last week’s What Matters Now here:

There's no paywall on The Times of Israel, but the journalism we do is costly. As an independent news organization, we are in no way influenced by political or business interests. We rely on readers like you to support our fact-based coverage of Israel and the Jewish world. If you appreciate the integrity of this type of journalism, please join the ToI Community.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel