Newly deciphered inscription gives clue to biblical Queen of Sheba’s Jerusalem visit

Discovered at the Ophel adjacent to the Temple Mount, seven letters on clay jar sherd are written in dialect and script stemming from the Arabian Peninsula, epigrapher suggests

Amanda Borschel-Dan is The Times of Israel's Jewish World and Archaeology editor.

After stumping epigraphers for over a decade, a mysterious First Temple-era inscription uncovered at the Ophel, a stone’s throw from Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, may finally have been deciphered.

According to a new study by Dr. Daniel Vainstub, the seven-letter inscription etched on a large clay jar records one of the ingredients found in the incense mixture used in the Temple — perfumed gum resin or labdanum.

According to readings of Exodus 30:34, aromatic labdanum (Cistus ladaniferus) is likely the second component of the Temple worship’s incense.

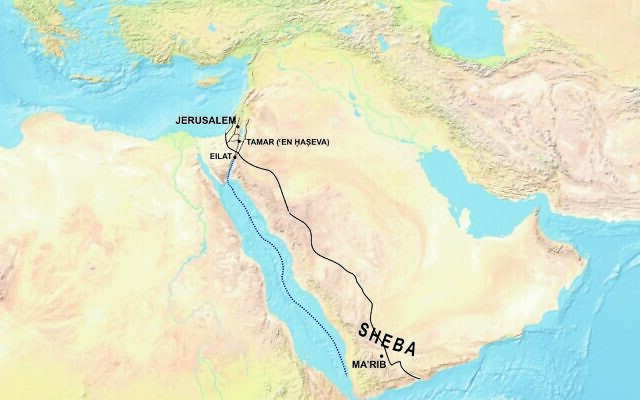

Vainstub believes the inscription’s writing and language stem from the Kingdom of Sheba — over 2,000 kilometers (1,240 miles) away.

This suggestion runs counter to the previous consensus opinion of a dozen top researchers who held it was written in the local script, Canaanite.

However, in a new study published Monday in the Hebrew University’s Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology, Vainstub suggests the script is Ancient South Arabian (ASA) and records what appears to be a Sabaean-language word. During the First Temple period, the Sabaean language was used in what is today’s Yemen, where the Kingdom of Sheba once stood.

If this is true, the Ophel inscription is the earliest Ancient South Arabian inscription found so far in the Land of Israel.

Because the inscription was incised in wet clay that originated in Jerusalem, Vanstub hypothesizes that the scribe was a native speaker from the Kingdom of Sheba who was involved in supplying the incense spices. This, he contends, points to previously unconfirmed strong trade ties between the two kingdoms.

It is not surprising that earlier attempts by researchers to decipher the inscription weren’t successful, Vainstub told The Times of Israel on Monday shortly before presenting his findings at the 48th annual Archaeology Congress.

“Although the scripts have the same distant ancestor, those who deal with Canaanite inscriptions today are not familiar with Ancient South Arabian script. And those who work with Ancient South Arabian are not familiar with Canaanite scripts,” he said. Vainstub recently incorporated his familiarity with ASA to decipher an ancient ivory lice comb, which arguably holds the earliest Canaanite sentence.

Back in 2012, seven large clay jugs, or pithos, were discovered during excavations conducted by the Hebrew University’s Dr. Eilat Mazar at the Ophel, adjacent to the southern Temple Mount. She noted that on the neck of one jug was inscribed a partially extant seven-letter inscription, which she dated to the time of King Solomon, circa 10th century BCE. Mazar died in 2021, but a recent study by Ariel Winderbaum appears to confirm Mazar’s dating.

A dozen epigraphers and archaeologists initially attempted to decipher the inscription. However, the only consensus reached was that it was written in Canaanite script, which led to the First Temple period’s proto-Hebrew.

According to Vainstub’s analysis, the partial inscription does not contain a “coherent text,” but three of the Ancient South Arabian script letters spell out the word “labdanum.” Another letter, similar to the Hebrew letter het, signifies the number “5.” Three other letters are inconclusive, he said.

The paper points to increasing awareness of “the ASA script and the languages spoken and written by the civilizations that developed in the southwest corner of the Arabian Peninsula as of the end of the second millennium BCE.”

This knowledge has “expanded enormously in recent decades,” he writes, due to three factors: increased inscription finds during scientific excavations of the area, new databases that chart the inscriptions, and the use of radiocarbon dating for palmleaf stalks and wooden sticks engraved with ASA inscriptions, which supplements epigraphers’ paleographic analysis.

The discovery of the sherd at the Ophel, considered to be a First Temple-era administrative center, ties in nicely with Vainstub’s reading of the inscription — gum resin used in the priestly incense.

In his article, he cites other sections of the Bible in which “aromatics and ‘the goodly oil’ were included among the goods stored in the royal treasure house (2 Kgs 20: 12–13; Isa 39: 1–2 ALTER).”

Likewise, Vainstub reminds us that the Roman-era Jewish historian Josephus Flavius writes that “the first opobalsamum plants came to Israel from the Kingdom of Sheba during Solomon’s reign as a gift to the king, and from this time onward, they were cultivated locally in two places, geographically and climatically similar to Sheba: ‘En Gedi and Jericho.”

Finally, Vainstub states that the Ophel inscription forwards the age-old debate surrounding the historicity of a visit by a delegation from the Kingdom of Sheba to King Solomon in the 10th century BCE (as related in the Book of Kings and Chronicles).

As he states in a Hebrew University press release, “Deciphering the inscription on this jar teaches us not only about the presence of a speaker of Sabaean in Israel during the time of King Solomon, but also about the geopolitical relations system in our region at that time – especially in light of the place where the jar was discovered, an area known for also being the administrative center during the days of King Solomon.

“This is another testament to the extensive trade and cultural ties that existed between Israel under King Solomon and the Kingdom of Sheba,” says Vainstub.