Lawyers vote for leadership of bar association, a key factor in selection of judges

Turnout high as top candidates trade barbs; victory of government ally over staunch overhaul critic could mean government will be able to remake judiciary without legislation

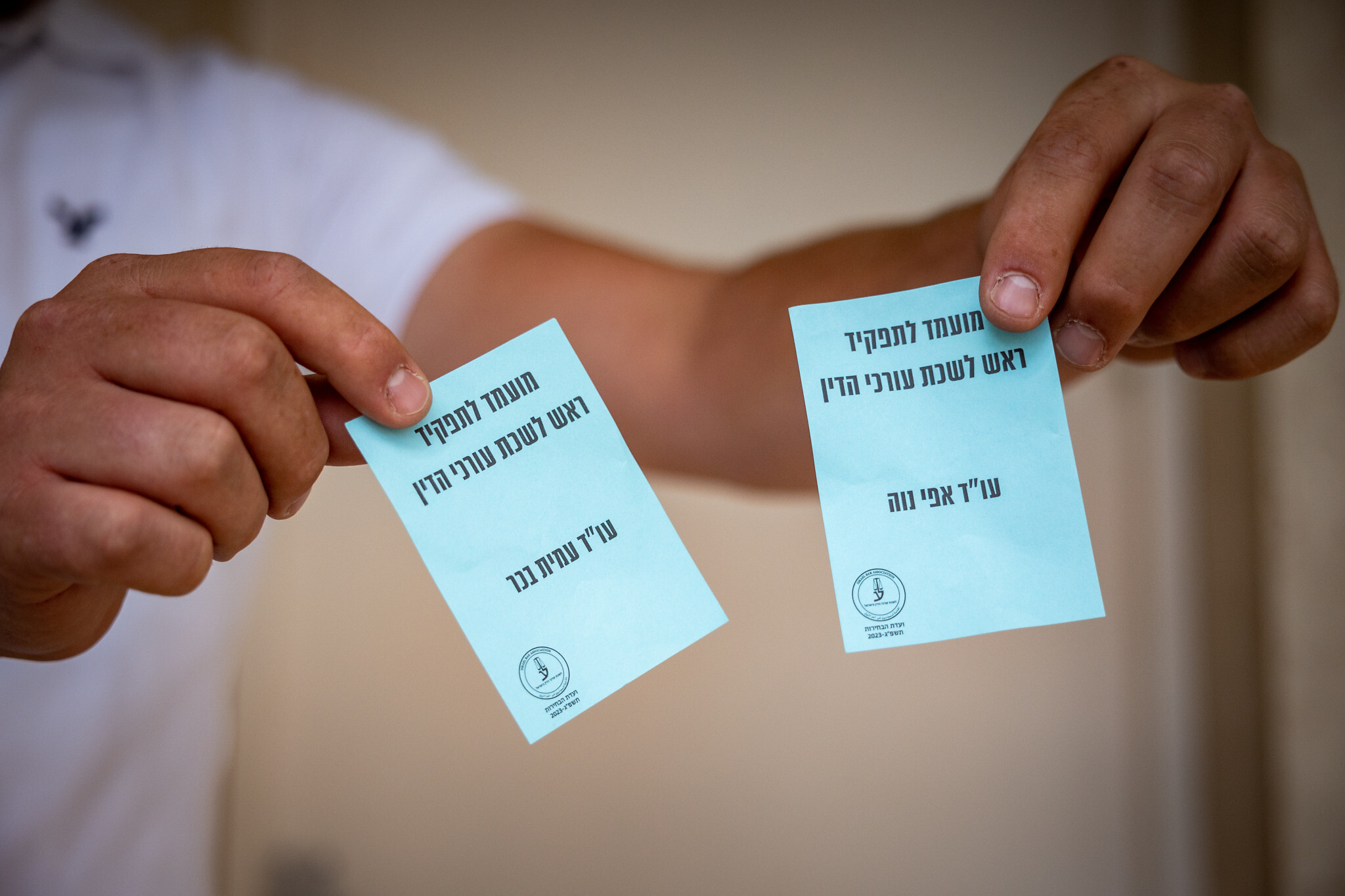

There were long lines at many polling locations across the country Tuesday as voting was underway for the leadership elections of the Israel Bar Association (IBA).

While the event, held every four years, usually goes largely unnoticed, this year it plays a key role in the government’s judicial overhaul plans, since the victors get to choose two representatives to sit on the critical Judicial Selection Committee, which selects the nation’s judges and is at the center of the government’s controversial bid to overhaul the judiciary.

More than 77,000 attorneys who are IBA members have the right to vote at 106 polling locations around the country.

As of 2 p.m., the IBA said around 20 percent of those eligible had cast their ballots. According to Hebrew media, voting was three times the rate of the previous bar association election at that time of day.

While there was no clear timeline for when results would be announced, it was expected that the votes would not be fully tallied until Wednesday morning. In order to be elected chair, a candidate needs to secure at least 40% of the vote. Failing that, the two leading candidates will head to a second-round runoff election in several weeks.

The two strongest candidates for the chairmanship of the IBA — Amit Becher, the interim head of the organization and head of the Hope for the IBA slate, and former IBA chairman Efi Nave, who is head of the One IBA slate — traded barbs on Tuesday morning.

Becher has aligned himself with the protest movement against the government’s overhaul program, and on Tuesday told the Ynet news site that “these elections are fateful for democracy, the independence of the judiciary is at stake.”

“We feel that there has been an awakening, and rightly so,” he said.

“In addition to the independence of the judicial system, respect for the legal profession is also on the agenda here. Unfortunately, the candidate running against me is a convicted criminal, who brought disgrace to the bar. There are many lawyers who are not willing to accept him,” Becher said.

Nave, who has strong backing from senior members of the government, was convicted last year of border fraud for smuggling his partner through passport control at Ben Gurion Airport in 2018 in order to avoid entanglements in the divorce proceedings he was involved in with his wife at the time.

And in 2019, Nave was arrested on suspicion of advancing the judicial appointments of women in return for sexual favors. The State Attorney’s Office eventually declined to prosecute Nave, since key evidence against him was obtained by illegally hacking his phone and was likely to be thrown out by the court.

Nave has expressed support for legal reform, although he has said that he opposes “large portions” of the radical proposals made by Justice Minister Yariv Levin at the outset of his judicial overhaul crusade.

Regardless, Nave is backed by senior coalition figures and government allies and is seen as likely to cooperate with Levin.

However, on Tuesday he said that he was not the “proxy” of the justice minister.

“My worldview is conservative, and I think the courts should not interfere in everything. I am not a proxy for Levin,” he told Ynet, claiming without evidence that his rival was funded by “extremist entities.”

The two other candidates running in the election for chair are Doron Barzilai, also a former IBA chairman, and Arkady Eligulashvili. According to a report by Channel 13 news, the coalition exerted political pressure against Eligulashvilli to try and convince him to drop out of the race in order to boost Nave’s chances of success.

Eligible voters will cast four ballots: one for the chairmanship of the IBA; another for the national party slates running to be elected to the IBA’s National Council, which is the “executive branch” of the organization; one for the chairmanship of the IBA’s district councils; and another for the district party slates.

The National Council will select the IBA’s two representatives for the Judicial Selection Committee. This pair will join the seven other members of the panel: two government ministers, two lawmakers (one of whom is from the opposition — Yesh Atid MK Karine Elharrar), and three Supreme Court judges.

Should those who prevail in the IBA elections be receptive to the wishes of the government, they could provide Levin substantial influence over the powerful committee and he could begin appointing judges — at least to the lower courts but potentially even to the Supreme Court — who share his worldview.

In such a situation, Levin would in effect be able to remake the judiciary in his image without the need to pass much of the divisive legislation.

Should the elections result in a situation where two representatives aligned with his ideology are elected, that would give the government five representatives on the Judicial Selection Committee.

That is enough to appoint judges to the magistrate and district courts, for which a majority of five members on the committee is required.

But since Levin has indicated he will seek to appoint a new Supreme Court president after current president Esther Hayut retires in October, the justice minister could conceivably assert even greater influence over the committee.

Although currently the Supreme Court president is, by custom, selected automatically according to seniority on the court, the law allows for the Judicial Selection Committee to appoint the president with a majority of just five.

Should pro-government IBA representatives be selected to the committee, Levin could then choose the new Supreme Court president, who then has the right to select the two other Supreme Court justices who sit on the Judicial Selection Committee.

Levin could therefore conceivably have as many as eight members of the committee allied with his worldview, enough to appoint new Supreme Court justices — which requires a majority of seven on the panel.

It should be noted that while there are at least four conservative justices on the Supreme Court at present, it is not certain that any are inclined to support Levin’s radical agenda against the judiciary, and Levin has previously said he doesn’t regard any current Supreme Court justice as sufficiently conservative.

If opponents of the government’s judicial overhaul plans win out in the IBA elections, the representatives they appoint to the committee will almost certainly be hostile to Levin’s plans.

In that case, Levin will likely refuse to convene the committee in the short term, and it also may spur him to push once again for the radical overhaul which, if passed, would give governing coalitions almost complete control over all judicial appointments in the country.