UK posthumously honors Jewish diplomat blocked by Saudis in 1968 for being a Jew

19 years after his death, the British Foreign Office dedicates the ‘Phillips Room’ to Sir Horace Phillips, who overcame socioeconomic hurdles to become a long-serving ambassador

Portrait of Sir Horace Phillips. (Courtesy of the British Foreign Office)

Portrait of Sir Horace Phillips. (Courtesy of the British Foreign Office) King Faisal of Saudi Arabia is shown during a vist to the State Department in Washington, DC, May 28, 1971. (AP Photo/John Duricka)

King Faisal of Saudi Arabia is shown during a vist to the State Department in Washington, DC, May 28, 1971. (AP Photo/John Duricka) Britain's Queen Elizabeth II and the Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlevi of Iran take their seats at the banquet the Shah gave in honor of the Queen at the Golestan Palace in Tehran, Iran on March 2, 1961. Queen Farah Pahlevi is visible in right background. (AP Photo)

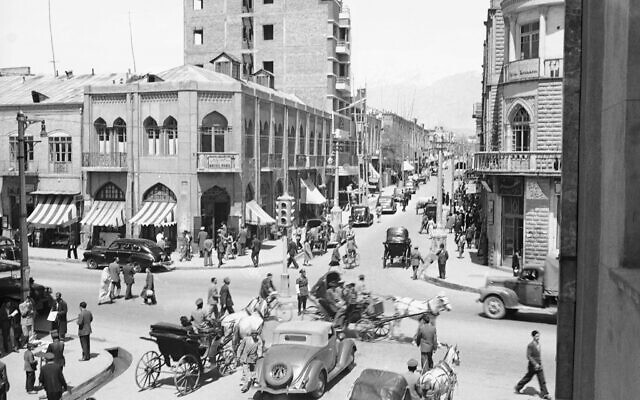

Britain's Queen Elizabeth II and the Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlevi of Iran take their seats at the banquet the Shah gave in honor of the Queen at the Golestan Palace in Tehran, Iran on March 2, 1961. Queen Farah Pahlevi is visible in right background. (AP Photo) Men and women, wearing the traditional burqa, walk along a street in Kabul, Afghanistan in 1951. It is one of three paved streets in the capital city. (AP Photo)

Men and women, wearing the traditional burqa, walk along a street in Kabul, Afghanistan in 1951. It is one of three paved streets in the capital city. (AP Photo)

LONDON — He was, Britain’s Foreign Office decided in 1968, “just the right man” to be the country’s ambassador in Saudi Arabia. With a string of previous postings in the Middle East, deep regional expertise, and a strong grasp of Arabic, London’s choice of Sir Horace Phillips was certainly a logical one.

Phillips and his wife packed their bags, Queen Elizabeth II signed the formal commission, and the Saudis approved the appointment.

The only problem: Phillips was a Jew and King Faisal was about to find out. When the Jewish Chronicle happily splashed the news across its pages, Riyadh took the unprecedented step of withdrawing its agreement to an appointment it had already accepted.

Last month, the British government helped to right this wrong, naming a room in the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s (FCDO) elegant central London headquarters after Phillips, the UK’s first Jewish career ambassador.

The grandson of Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe, Phillips was anything but the upper-middle-class, privately educated, Oxbridge alumni who dominated the ranks of Britain’s diplomatic service at the time.

And, despite his later admission that the incident was both “extraordinary” and “traumatic,” the Saudis’ snub hardly blighted Phillips’s career. Having served in Iran, Afghanistan, Yemen, Bahrain, and even Saudi Arabia, he went on to become Britain’s top diplomat in Indonesia, Tanzania and Turkey.

While Phillips died nearly 20 years ago, the FCDO’s decision to honor him on the 75th anniversary of his joining the diplomatic service has been welcomed by Jewish observers.

“The British Foreign Office has had a very patchy record historically when it comes to Jews and Israel, and there have been various instances of outright antisemitism,” British journalist Tom Gross told The Times of Israel. “So this is a very welcome development by the Foreign Office to honor Horace Phillips, especially their belated recognition that it was, of course, wrong and hurtful for the Saudis to refuse his appointment as British ambassador to Riyadh in 1968 on the grounds that he was Jewish.”

Sir Philip Barton, the head of the FCDO and Britain’s diplomatic service, was joined by Phillips’s daughter, Maureen, at the event marking the opening of the “Phillips Room.” It was also attended by members of the FCDO’s Jewish staff network, which is named the Horace Society.

“The Phillips Room honors the outstanding contribution of Sir Horace and all the FCDO’s Jewish staff, past, present and future. By dedicating this room to him, we have an opportunity to share his story with staff and visitors to our King Charles Street building. That story includes Sir Horace’s remarkable achievements but also recognises the challenges he faced, and that our Jewish colleagues can still face today,” Barton said in a press statement

The Phillips Room features a new display of works from the Government Art Collection, which reflect Phillips’s Jewish heritage and his socio-economic background and give an insight into his diplomatic career, focusing on his postings in Saudi Arabia, Indonesia and Turkey, the FCDO statement added.

Try, try again

Born in 1917, Phillips first dreamed of joining the foreign service in his early teens as he read books about “what was then the far-flung Empire and… the exploits of great Arabian explorers — [Charles] Doughty, Bertram Thomas.” But his first efforts to join were rebuffed by the civil service, which made it quite clear that his lack of a university education and his family’s limited resources — at the time, budding consular staff were expected to spend a year abroad learning a language at their own expense — meant it wasn’t even worth him taking the entrance exams.

Phillips’s parents had hoped that their son, who had won a place at one of Glasgow’s leading state schools, might be able to get a need-based financial grant and go to university. Those hopes, however, were snuffed out when his father — a commercial traveler, salesman, and finance house manager — died when Phillips was 18. With his mother left with seven children and no money, young Horace was forced to find a job and help the struggling family. After passing its exams, he landed a post in the domestic civil service’s Inland Revenue, the body responsible for collecting taxes and customs. However, he was called up soon after the outbreak of World War II and remained in the army until shortly after India was declared independent from Britain in 1947.

The war helped to break down, but by no means eliminate, some of the harshest aspects of Britain’s then-rigid class system, and Phillips, who hadn’t lost his ambition to join the foreign service, was a grateful beneficiary. Even as hundreds of thousands of young men were still fighting the Nazis, the government announced it would ease access to veterans who wanted to join its diplomatic outposts abroad. Entrance exams were to remain in place, but they were no longer to be so highly academic.

“In a way, you might say that the examination was based on experience in the university of life or the university of war,” Phillips recalled in an extensive 1997 interview with Churchill College, Cambridge’s British Diplomatic Oral History Program. Unsurprisingly, Phillips — whose aptitude for languages was evident when he learned to speak fluent Japanese in order to interrogate prisoners of war — passed, and soon received his first posting to Shiraz, in Iran, in late 1947.

Changing with the times

Phillips’s junior status as a vice-consul in the southern city gave him plenty of time to study Persian and to gather political intelligence. It also provided an early insight into Britain’s much-diminished role in the region.

“Old tribesmen would come into the consulate and kiss my hand and in effect ask if I could get their son or some other relative a seat in the Majlis [parliament] in Tehran,” he said. “This approach was an interesting legacy of the old days when the British were influential in the country and could do things like that. The tribesmen could not understand why post-war and post-India that influence had declined, so I had to mollify them.”

Two years later, Phillips was promoted and sent to Kabul where his duties included keeping tabs on the local Afghan political scene and press and taking his turn to accompany the embassy’s aging truck on its monthly journey through the Khyber Pass to pick up supplies in Peshawar, across the northwest border in Pakistan.

The Foreign Office was keenly aware of the sensitivities of sending British Jews to certain Middle Eastern states and spent time mulling whether to post Phillips to Saudi Arabia as first secretary — deputy to the ambassador — in 1953. Phillips, however, was determined to go.

“It did not seem to me to matter one jot; I was going out as a British diplomat, and after all, the civil service and the Foreign Office don’t ask if you are Catholic, Methodist, Buddhist, Jew, or whatever,” he recalled telling his superiors at the Foreign Office. We may not mind, but the Saudis might, came the response. In the end, Phillips said he was prepared to take the risk and the appointment went off as planned. Indeed, at a moment of tensions between the two countries over a territorial dispute, the Saudis blocked Britain’s new ambassador from taking up his post, leaving Phillips in charge of the embassy for several months.

Phillips’s experience of the Middle East was buttressed by three further appointments — to Aden, then one of the last outposts of the British Empire in 1956; back to Iran as deputy ambassador in 1960; and to Bahrain in 1964 — before he received his own embassy when he was sent to Jakarta in 1966.

“Why Indonesia? Well, cynically I reflected that it was a 3,000-mile archipelago 7,000 miles away, and the Foreign Office must have thought I couldn’t do much damage there, so let’s try him!” he later joked to the Churchill College program researchers.

An international non-incident

As the Foreign Office recognized, Phillips’s performance in the Muslim-majority country — then undergoing immense political turmoil with the onset of the brutal Suharto military regime — would have stood him in good stead to lead Britain’s diplomatic presence in Saudi Arabia. But Faisel’s about-turn on learning Phillips was Jewish meant this was not to be. When the UK government broke the news to the House of Commons, it sparked an outcry with press suggestions that Britain should break off relations with the Saudis. Phillips took a more phlegmatic view. “Of course, I agreed with the [Foreign] Office that this was nonsense,” he said in 1997. “We had more interests in our relations with that country than the posting of me there.”

While he remained publicly silent — to escape the press frenzy, the Foreign Office sent Phillips and his wife on leave to Greece for six weeks — the hurt was apparent in a private letter he wrote to the Daily Telegraph’s obituary desk in 1980. “You may think it presumptuous of me to write this,” it stated. “But just in case, when the time comes, I merit an obituary, could the following be borne in mind, please?”

Phillips continued with a passage that appeared in the paper’s eventual obituary 24 years later: “When, in March 1968, King Faisal withdrew his agreement to my appointment as next British Ambassador to Saudi Arabia because I am a Jew, it was widely stated in the British press that I was an ‘ex-Jew’ or a ‘non-practising Jew.’ Some of this may have been inspired by official comment seeking to play down the embarrassment. As a serving diplomat, I could not myself reply. But the fact is that I have always been a practising Jew, and am to this day a member of Garnethill Synagogue in Glasgow, where I was brought up in the tradition. Any statement to the contrary in an obituary would give great pain to my family and friends, and dishonour my memory in the Jewish community.”

As the former ambassador’s letter suggested, the Foreign Office’s embarrassment was acute. “The Foreign Office could now unfairly look like fools for not knowing about his Jewishness or, alternatively, like extravagant optimists in supposing they could get away with appointing a Jew to an Arab country,” one commentator said at the time. “Most probably, in fact, they did not think there was anything to get away with; or, if there was, that they had got away with it long since, for Phillips had served in Saudi Arabia… before without objection, and his standing there was first-rate.”

In retirement, Phillips simply commended the Foreign Office. “It supported me throughout and never lost confidence in me,” he told the Churchill College program, citing his swift appointment as High Commissioner in Tanzania (Britain’s ambassadors in Commonwealth countries, and their representatives in London, are termed High Commissioner). It was a potentially tricky appointment: Phillips was London’s first man in Dar es Salaam after Tanzania had broken off diplomatic relations with Britain in 1965 in a dispute over the UK’s handling of Rhodesia’s unilateral declaration of independence. Nonetheless, Phillips quickly built a strong relationship with then-president Julius Nyerere and adeptly defused a row in 1970 over false rumors that Britain was planning to resume arms sales to South Africa’s apartheid regime which had threatened to split the Commonwealth.

Three years later, Phillips was sent to Turkey as British ambassador. He again found himself involved in complex international affairs, grappling with the crisis surrounding Turkey’s 1974 invasion of Cyprus and the island’s subsequent (and continuing) division. Phillips remained in Turkey until 1977, when he retired aged 60.

Summing up his career for researchers in 1997, Phillips simply said: “Like a traditional Jew, I can only reflect on how proud my mother would have been.”

There's no paywall on The Times of Israel, but the journalism we do is costly. As an independent news organization, we are in no way influenced by political or business interests. We rely on readers like you to support our fact-based coverage of Israel and the Jewish world. If you appreciate the integrity of this type of journalism, please join the ToI Community.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel