Now on display, UK Jews’ correspondence shows the Holocaust unfolding in real-time

At London’s Wiener Holocaust Library through June 16, an exhibit of letters from WWII tracks the spread of information by Jews seeking to protect loved ones from the Nazis’ web

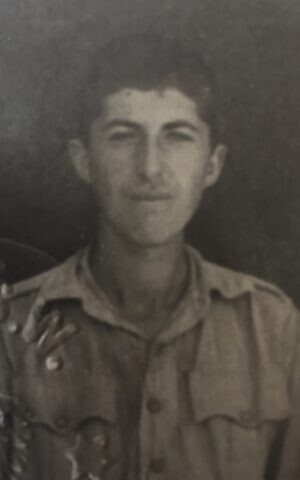

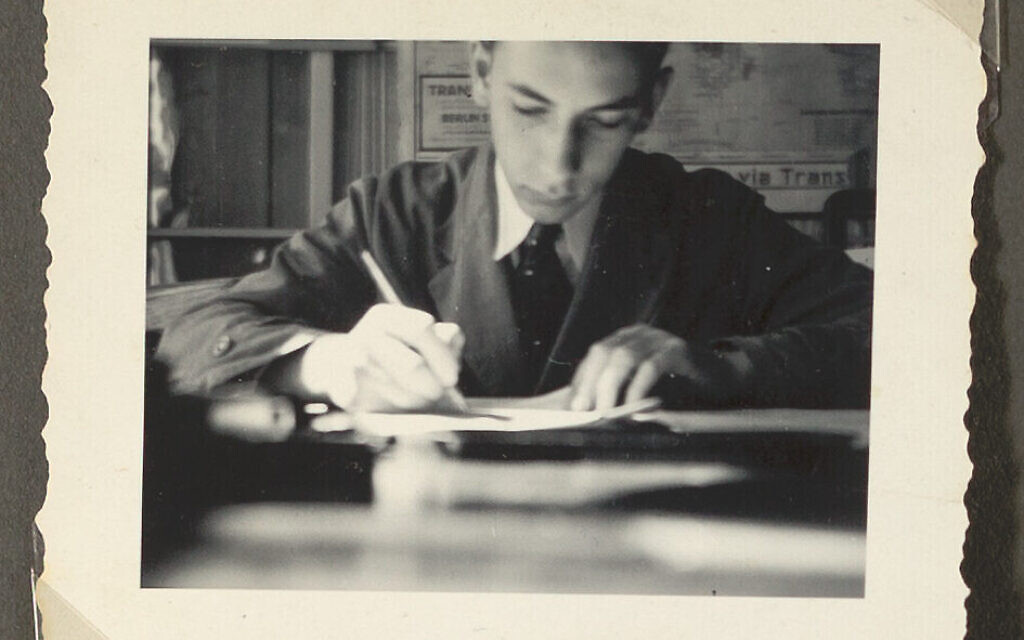

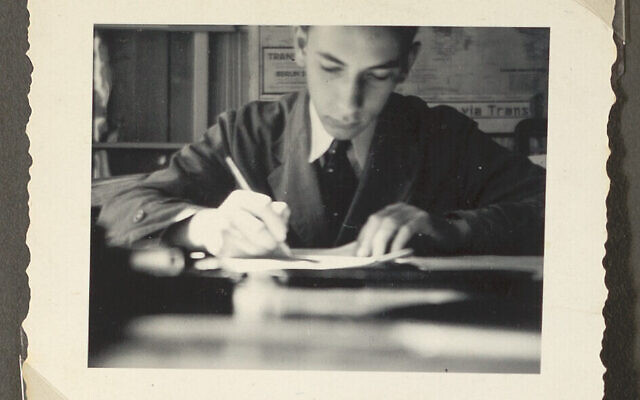

Friedel Jaffe working as a clerk in the Berlin office of Adler and Oppenheimer in 1936. (Courtesy Deborah Jaffe)

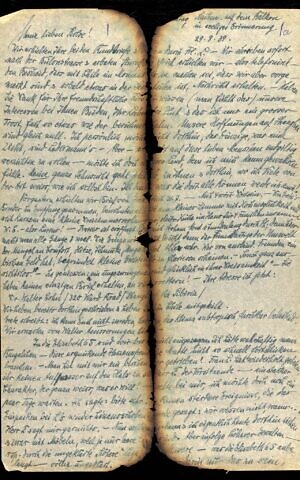

Friedel Jaffe working as a clerk in the Berlin office of Adler and Oppenheimer in 1936. (Courtesy Deborah Jaffe) A singed letter from the Holocaust on display at the Wiener Holocaust Library in London. (Courtesy)

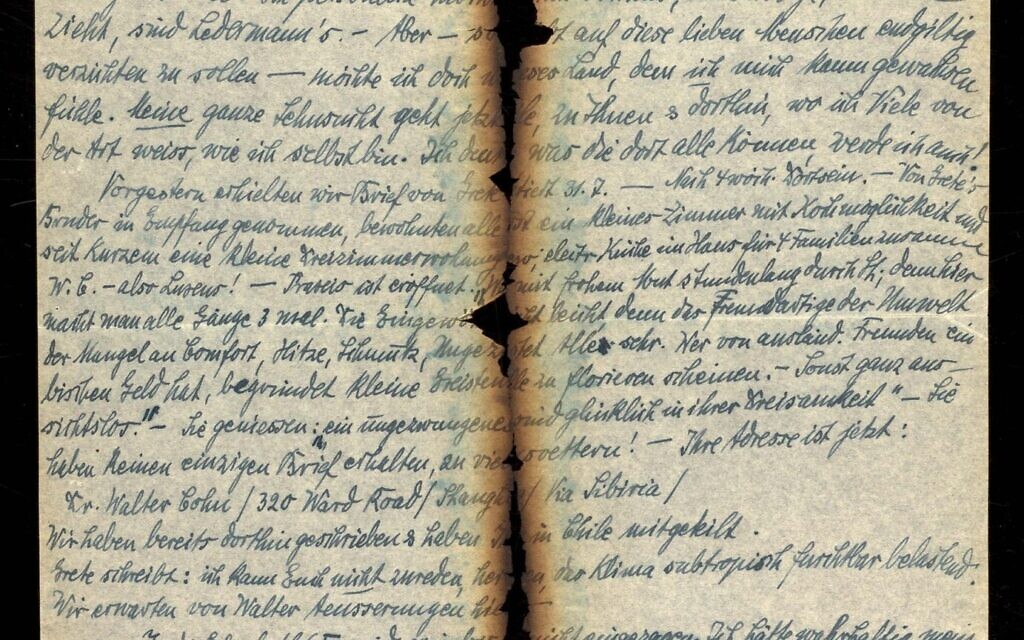

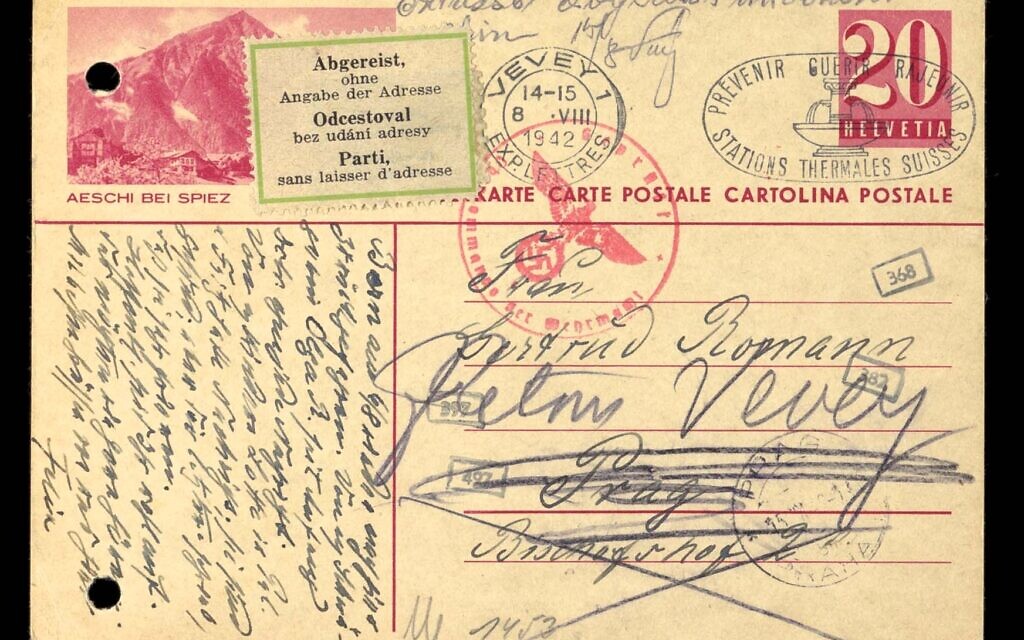

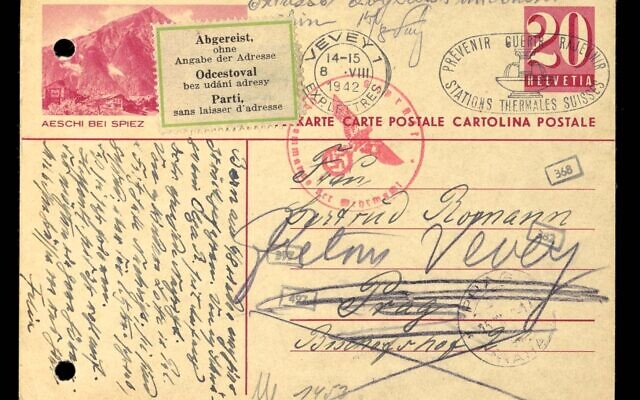

A singed letter from the Holocaust on display at the Wiener Holocaust Library in London. (Courtesy) A postcard marked, 'Departed without leaving a forwarding address,' from the family papers of the Hepner and Cahn: families. (Courtesy of the Wiener Holocaust Library Collections)

A postcard marked, 'Departed without leaving a forwarding address,' from the family papers of the Hepner and Cahn: families. (Courtesy of the Wiener Holocaust Library Collections) Deborah Jaffe speaks at the exhibition at the Wiener Holocaust Library in London, February 23, 2023. (Adam Soller Photography)

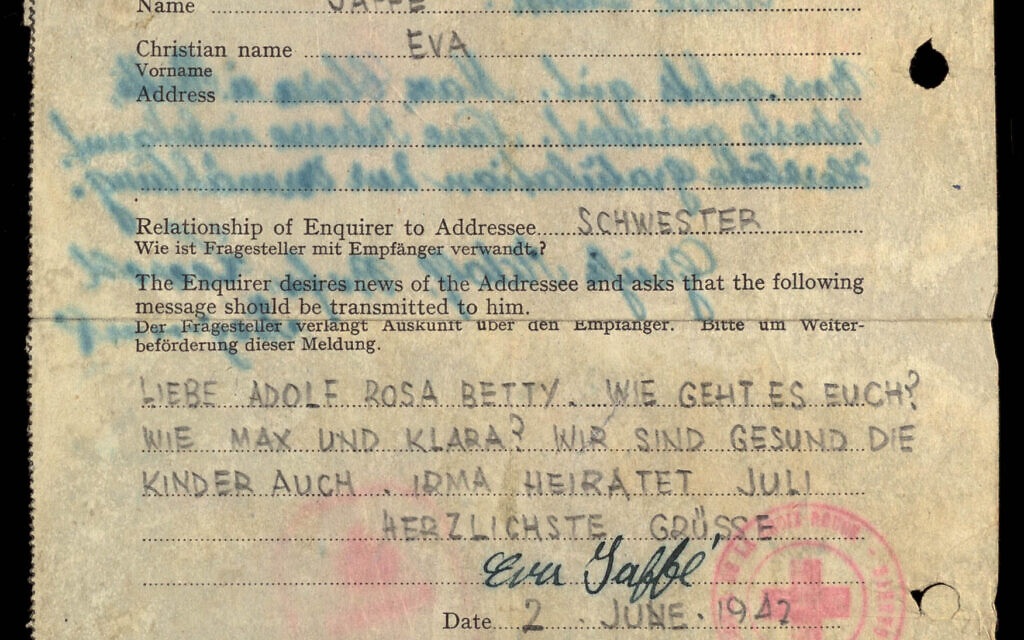

Deborah Jaffe speaks at the exhibition at the Wiener Holocaust Library in London, February 23, 2023. (Adam Soller Photography) A letter from Eva Jaffe to Rosa Dahlerbruch dated June of 1942. (Courtesy of Deborah Jaffe)

A letter from Eva Jaffe to Rosa Dahlerbruch dated June of 1942. (Courtesy of Deborah Jaffe)

LONDON — When Deborah Jaffé’s mother died 15 years ago, she discovered in her cellar two damp and moldy folders bearing a distinctive German font and containing 200 typed letters.

Written by her father on his beloved Continental typewriter in the two years leading to the outbreak of war in September 1939, the letters were addressed to family members who had escaped Nazi Germany, as well as those who had not yet got out.

Despite only understanding a smattering of German, Jaffé immediately sensed the significance of her find — one that would ultimately reveal far more about her family’s tragic history than she had previously been told.

A few of Jaffé’s carefully conserved and translated archive of letters feature in “Holocaust Letters,” an exhibition at London’s Wiener Holocaust Library that runs through June 16.

With its heartbreaking final letters, desperate appeals for help, and grim premonitions of impending disaster, the exhibition underlines the importance of correspondence as the earliest form of Holocaust knowledge.

It details the harsh constraints and rules imposed upon the embattled Jewish communities of Nazi-occupied Europe as they attempted to communicate with friends and family.

And it shows the importance of the letters today, both for the descendants of survivors and those who perished, and for wider public understanding of the Holocaust.

“The letters are the sites where knowledge was produced, as well as evidence of knowledge itself,” the exhibition explains. “Jewish persecutees wrote to their families and friends to share practical knowledge of threats that faced them. They amassed a powerful understanding of the Holocaust that moved them to act urgently, often on behalf of others.”

The materials contained in the exhibition demonstrate the raw, varied and paradoxical emotions within Holocaust letters.

The sudden arrival of mail from friends and relatives from whom nothing had been heard for weeks or months could produce a “calming and restorative” effect. Some correspondents even describe them as “lifesaving.”

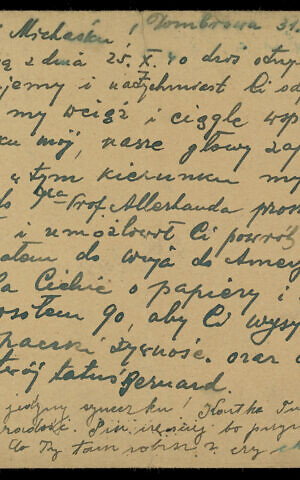

“Your long-awaited postcard has filled our hearts with joy. You’ve saved us for what would our lives be worth without you?” Bernard Rechnic replied to his son, Michał, who had been deported by the Soviets deep inside Russia following Stalin and Hitler’s carve-up of the family’s native Poland in 1939. Similarly, Mauthausen survivor Hans Maršálek said: “The letters from home were building blocks of hope and an irreplaceable incentive not to give up.”

At the same time, the absence of letters – or the worrying, dreaded or terrible news they sometimes bore – could produce very different emotions.

“My mother’s last letter from Ravensbrück was dated December 1944,” recalled Rolf Kralovitz. “In the months that followed, I waited eagerly for further news from her. Nothing. Also from my sister: nothing. Also from my father: nothing. In vain I awaited a signal of life. But dead people do not write.”

Throughout wartime Europe, there was strict censorship and tight, often changing, postal regulation. In late September 1939, the Nazis imposed a ban on correspondence between Germany and enemy countries. While it imposed censorship, the British government adopted a more lenient approach, allowing families to remain in contact with relatives in Germany and occupied countries through Thomas Cook’s “undercover mail” service via neutral Lisbon.

For concentration camp inmates, there was a battery of further rules and regulations. Prisoners could, for instance, only send mail to registered relatives, and only on “writing days.” Correspondence — in which it was forbidden to talk about working conditions, politics or life in the camp — had to be written in German and was read by both a Block Leader and the censorship office. While inmates often deployed code — or attempted to utilize informal or illegal channels — to get around restrictions, fear of punishment for breaking the rules was ever-present. Nor were prisoners allowed the comfort of holding onto correspondence from home: they were only permitted to keep the most recent letter they had received.

The Nazis also attempted to use correspondence to spread fake news. “Operation Mail” in the summer of 1942 aimed to propagate false information about the camps — prisoners had to suggest that they were in good health and that their “resettlement” was fine — and to uncover addresses of Jews in Nazi-occupied territories. The Third Reich’s bureaucracy also dutifully but opaquely recorded the departure of those deported to the East. Correspondence sent to the home addresses of those sent to the camps was stamped “departed without leaving a forwarding address.”

As the exhibition shows, while Jewish correspondents weren’t yet using the term “Holocaust” — it was first used in connection with the murder of European Jews by the New York Times in 1943 — their euphemisms accurately captured and interpreted the unthinkable rumors and informal news which they were communicating to one another.

“Save my parents before the war begins,” one correspondent prophetically wrote in May 1939. Germany is “drifting towards some disaster,” warned another in January 1940. By late 1941 and early 1942, phrases such as “the German conditions,” “the new era” and “the fate of our friends in the camps” begin to appear in letters. And from 1942, “Poland” regularly features in letters. Although the precise details of mass genocide weren’t yet widely known, the transports and the lack of correspondence from those deported to the East meant it had become suggestive of something terrible.

“If we go to Poland, we can be confident life will end,” Gertrud Hammerstein wrote to her daughter and son-in-law from Berlin in October 1942.

Reading between the lines

The degree of contemporary knowledge about the unfolding horror shared by other writers in their letters is revealing.

A postcard from Frida Motulski in Berlin to her friend Hugo Zwillenberg, a German-Jewish émigré in Holland, shows her understanding of the Holocaust in March 1942. She saw the links between domestic relocations, military priorities and the systematic nature of the deportations, while recognizing that the unpredictable destinations and fates of the deportees indicated that what was underway was both dynamic and aggressive.

While noting that “we are all healthy” and “for the moment everything is as it used to be,” she continued: “We cannot relax. Every day brings new commotions, especially because these days various transports are leaving again, and once more, we know people on each one.” Naturally, she noted, “We cannot help but wonder when it will be our turn.”

The lack of news from family and friends “worries us dreadfully,” Motulski wrote — although when correspondence did arrive, she learned to read between the lines and treat it with suspicion. “The last card from Erna, who always wrote regularly, sounded so odd,” she wrote, connecting this to rumors that the residents of Ghetto Piaski, where her niece had been taken, were about to be “moved on,” possibly to Ukraine.

A haunting last message from Maria and Maximilian Wortmann, written from a railway siding at the Warsaw Ghetto before their imminent journey to Treblinka, shows the fearful parents appealing to a distant cousin to help them. “Ludwik, please do what you can,” they write. “If there is no return for us, take care of Dziunia. You are the only ones remaining,” the note concludes. A separate note to their daughter, asks her to be “brave and cope,” while also telling her where food and money — described in code as “Butter is in the wardrobe” — have been hidden away.

But Holocaust letters aren’t simply about the words on the page. They are “objects which contain layers of meaning beyond the messages they carry,” the exhibition notes. “Their markings, condition, script, paper weight, texture, and other physical characteristics point to information beyond the content.” Graphic stains on one letter and burn marks on another speak volumes.

The role of Jewish émigrés — “the keepers of early Holocaust knowledge,” in the words of the exhibition — was particularly important in assisting loved ones left under the cosh of Nazi rule. Before the war, they wrote with family news and sent food parcels and other everyday items. After 1939, émigré letters combined a desperate, frantic effort to get family and friends out of Hitler’s Europe with a recognition that, whatever discomforts they currently endured, they were the lucky ones.

In April 1939, for instance, Josef Heilbronner told his friend Moritz Altstadt in London about his arrest and incarceration in Buchenwald after Kristallnacht. Having obtained a temporary laborer permit for Palestine, he was released from the camp after 10 days. From his new home, he wrote: “Life is not easy here, but one accepts everything willingly because, at last, one can breathe freely again.”

And, of course, while they were still able, those in the camps attempted to encourage their families to leave. Writing from Lichtenburg concentration camp in late December 1938, Dr. Hedwig Leibetseder told her family: “I know that one day life will come again. I am ready. I love you, kiss you and hug you. Stay brave and healthy.” She concluded with two simple, but telling, commands: “Emigrate. And write.”

A life revealed in full

One such émigré was Friedel Jaffé, a young apprentice clerk who had worked in the Berlin office of Adler and Oppenheimer. He managed to escape to Britain in early 1939 thanks to the company’s decision to open a factory in Lancashire, in England’s northwest.

Until she discovered his letters some 70 years after his arrival in the UK, his daughter believed she knew his story.

“I’d grown up thinking I was one of the lucky ones in that my father had told me what had happened,” she told The Times of Israel. “I was very aware of other people like me whose parents did not tell them what had happened. I thought I was quite fortunate.”

But, Jaffé continues, “What I was told, I now realize, was his official story. He’d made an official version and it never deviated.”

The stash of letters, telegrams, train tickets and emigration and application forms which Jaffé believes may have been left for her to find — revealed far more than the carefully curated story Friedel had shared with his daughter.

“I think that happens when we have great trauma in our lives,” she says. “You compartmentalize it because there are certain areas you can’t deal with and you don’t talk about them.”

That trauma is laid bare in the letters. “The letters convey the harrowing story of a young man trying to escape: to get anywhere, work, have a future, and learn English,” Jaffé explains. “There are false hopes, freedoms taken away and concern for family, especially his parents Abraham and Eva living in Castrop Rauxel.”

There was a lot to be concerned about. Abraham had been arrested after Kristallnacht and sent to Sachsenhausen for six weeks. Days later, Friedel shared the news cryptically with his brother who had already emigrated. Hiding it in an innocuous paragraph, he wrote: “Nothing has changed here in the meantime. Dear Papa is not at home at the moment.” From London, Irma, Friedel’s sister, used similar code to urge her brother to take care of himself. It was “so easy to catch something” in “this autumnal weather,” she suggested.

But her father’s folders also revealed what Jaffé terms “letters by the missing” — correspondence from, and about, family and friends who did not survive and of whom she had never heard mention.

A May 1938 letter from Friedel to his parents spoke of correspondence he has received from “Uncle Max,” Eva’s brother, who had evidently been working on emigration plans for the whole family. “He’s woken up a bit too late,” Friedel feared.

Just over six months later, Max Rohrheimer wrote to Friedel’s parents, pleased to hear that Abraham has been released and that he and Eva now had papers allowing them to leave the country. Max hoped that they could meet before Abraham and Eva departed for England. He wrote of his own — ultimately thwarted — efforts to escape: “We’ve guarantees for the USA but our number is high.”

While Abraham and Eva arrived in Britain shortly after their son, their in-laws — Eva’s brother Max and his wife, Klara, and sister Rosa Dahlerbruch and her husband Adolf and daughter Betti — were not so fortunate.

In what was probably the last correspondence Eva had with her sister, a short Red Cross letter in June 1942 says: “How are you, Adolf and Rosa? And Max and Klara? We are well, so are the children. Irma will marry in July.” Rosa’s response hints at Max and Klara’s deportation: “We are all fine. Max, Clara and Betti have different address. New address unknown. Many congratulations on the wedding.”

Jaffé doesn’t regret her journey of discovery — one involving translators, searches through archives and painful revelations — over the past 15 years.

“I think finding out all this has helped me no end because what had happened was a void and now I know,” she says.

Poignantly, at the London offices of World Jewish Relief, she found that her grandfather had registered his arrival in the UK, together with that of his son and wife. The archive also contained blank cards with the names of Max, Klara, Adolf and Betti — who Abraham had also registered in the hope they would come.

In her father’s folders, Jaffé also found a brown envelope. Bearing his distinctive spiky handwriting, it contains Abraham’s postwar correspondence with the War Organisation of the British Red Cross, the Order of St. John, Jewish Refugees Committee and World Jewish Congress Tracing Office seeking news of the close-knit family.

“Briefly and starkly, they reveal the names of these relations and their fates,” says Jaffé. On the front of the envelope, Abraham has simply written: “Murdered by the Germans under the Government of the Hitler Monster.”

There's no paywall on The Times of Israel, but the journalism we do is costly. As an independent news organization, we are in no way influenced by political or business interests. We rely on readers like you to support our fact-based coverage of Israel and the Jewish world. If you appreciate the integrity of this type of journalism, please join the ToI Community.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel