How Austria’s Jewish chancellor helped country evade responsibility for Nazi past

A new book by Israeli diplomat Daniel Aschheim examines Bruno Kreisky, Austria’s longest-serving leader, and his ambivalent relationship with his own Judaism and the Jewish state

Yasser Arafat, left, Austrian chancellor Bruno Kreisky, and former West German chancellor Willy Brandt at a press conference after three days of talks on the Middle East situation in Vienna, July 11, 1979. (AP Photo)

Yasser Arafat, left, Austrian chancellor Bruno Kreisky, and former West German chancellor Willy Brandt at a press conference after three days of talks on the Middle East situation in Vienna, July 11, 1979. (AP Photo) Former US Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, right, with Bruno Kreisky speak before the start of talks between US and Soviet foreign secretaries in Vienna, May 19, 1975. (AP Photo/Endlicher)

Former US Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, right, with Bruno Kreisky speak before the start of talks between US and Soviet foreign secretaries in Vienna, May 19, 1975. (AP Photo/Endlicher) Austrian chancellor Bruno Kreisky, center, is greeted upon his arrival for a visit to the United States, February 4, 1983. (US DoD photo by SGT Michael W. Tyler/ Public domain)

Austrian chancellor Bruno Kreisky, center, is greeted upon his arrival for a visit to the United States, February 4, 1983. (US DoD photo by SGT Michael W. Tyler/ Public domain) Bruno Kreisky with fellow socialist leaders Helmut Schmidt and Willy Brandt in Nuremberg, May 20, 1979. (Bundesarchiv bild)

Bruno Kreisky with fellow socialist leaders Helmut Schmidt and Willy Brandt in Nuremberg, May 20, 1979. (Bundesarchiv bild)

LONDON — For more than a decade after he came to power in 1970, Bruno Kreisky dominated Austrian politics and placed the small central European country firmly on the world stage.

Born to an upper-middle-class Jewish family, Kreisky was Austria’s longest-serving chancellor, winning four consecutive terms in a country with a long and dark tradition of antisemitism.

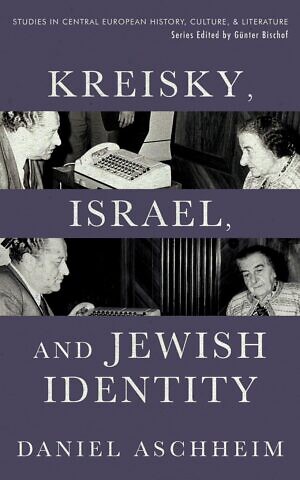

But as Israeli diplomat Daniel Aschheim explores in his new book, “Kreisky, Israel and Jewish Identity,” in the eyes of many, Kreisky’s personal and political achievements were colored — if not tainted — by his “ambivalent and often-confrontational relationship with his Jewishness, Jews, and Israel.”

Imprisoned by the Gestapo soon after the Anschluss, the youthful Kreisky managed to escape Austria and spent World War II in Sweden. At least 20 members of his family weren’t so lucky and perished in the death camps.

But after he returned to Austria in 1945, Kreisky helped to propagate — and throughout his years in office sustain — the convenient myth that his homeland had been the passive first victim of the Nazis; a myth which, for at least four decades, brushed Austria’s complicity in the Third Reich’s crimes under the carpet.

As the country’s Socialist chancellor, Kreisky unapologetically appointed former Nazis to his government; engaged in a virulent and bitter feud with his Nazi-hunting fellow Austrian Simon Wiesenthal; and publicly defended conservative Kurt Waldheim when he was accused of war crimes during the 1986 presidential election.

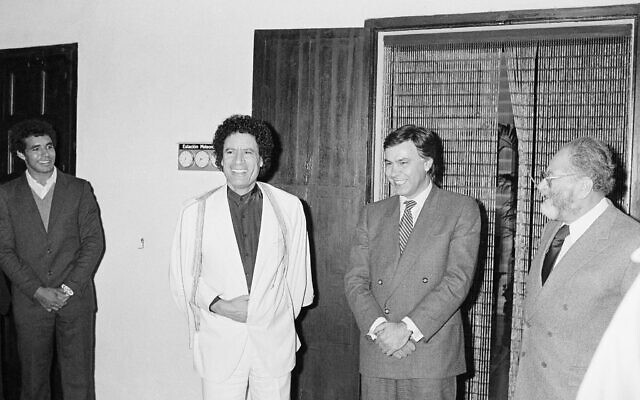

And Kreisky — a trenchant anti-Zionist — repeatedly criticized Israel in harsh terms while lavishing praise on Arab despots and dictators. After rolling out the red carpet for Yasser Arafat, the chancellor became the first Western leader to officially recognize the PLO. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Kreisky was a regular target of the Israeli press, which labeled him a “self-hating Jew.”

In Aschheim’s fascinating and scrupulously balanced telling, traces of the future chancellor’s outlook can be seen in his liberal upbringing in fin-de-siecle Vienna. While Kreisky’s family wasn’t observant, they did not deny their Jewish background. Comfortably integrated in the tolerant, multi-ethnic Hapsburg Empire, they rarely encountered antisemitism.

As a teenager, however, Kreisky jettisoned Judaism for socialism. Nor did he have much time for Zionism, placing huge store in his Austrian national identity, while sharing the disdain in which many assimilated Jews held the supposedly backward-looking, ghetto-dwelling “Ostjuden.” Throughout his life Kreisky would often refer to the “Jewish faith,” rejecting the very notion of a Jewish people.

As he swiftly rose through the ranks of early postwar Austrian politics, Kreisky defined himself simply as an Austrian socialist, rejecting the notion that his Jewish roots shaped his political identity. “One looks at the religious affiliation, which is in my case my Jewish heritage, as a private thing,” he declared.

At the same time, Kreisky was sensitive to the accusation that he wished to downplay being Jewish, and was privately keenly aware of the current of antisemitism which lay just beneath the surface of Austrian society. He later admitted that he was deeply hurt during his first, successful run for chancellor in 1970 to be confronted by a campaign presenting his conservative opponent as “a true Austrian.”

Nonetheless, as Aschheim’s book skilfully outlines, for many Austrians, Kreisky’s Jewish identity was intimately tied to the country’s cozy delusions about its supposed status as “the Nazis’ first victim.” Unlike Willy Brandt, the German chancellor, Kreisky opted not to lead a painful process of reckoning with the past. Instead, he chose to prove his “Austrianness” to the electorate by helping to cement and further this “national consensus.”

However, Aschheim tells The Times of Israel, Kreisky’s motivations weren’t purely a matter of political calculation.

“He was an Austrian patriot. He believed Austria was hijacked by the Nazis and that Nazism wasn’t something that was truly embedded in Austrian society,” Aschheim says.

Austria, Kreisky argued, needed to avoid getting “stuck in the circle of revenge,” pursuing what he termed the “small Nazis” whom he differentiated from Hitler’s elite. “We would never have found peace,” the chancellor revealingly said, had the country pursued the several hundred thousand Austrians who joined the Nazi party, let alone the “millions of people who didn’t open their mouth[s] although they knew what was happening.”

The impact of Kreisky’s stance was crucial. As the sociologist Karin Stögner argued, he became in essence the “alibi Jew,” providing Austrians with “what they were looking for: first-hand legitimation to ward off memory and responsibility.”

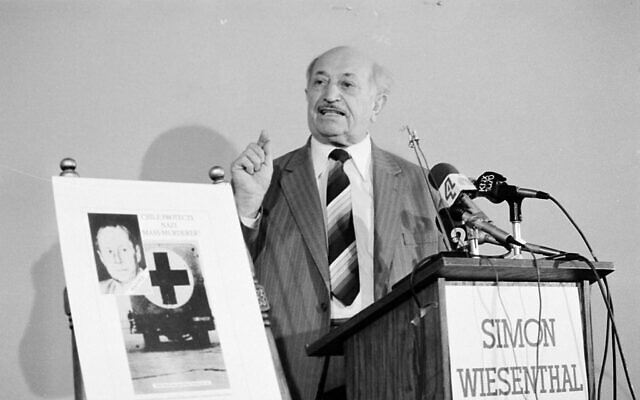

On Kreisky’s watch, past crimes intruded onto the contemporary political landscape on a number of occasions — setting the scene for a vitriolic showdown between Austrian’s two most prominent Jews.

Soon after Kreisky took office in 1970, Wiesenthal revealed to the German magazine Der Spiegel that Kreisky’s new cabinet included five former Nazis, including Otto Rösch and former SS member Hans Öllinger. In response, Kreisky — whose defenders claim he was unaware of their backgrounds and was, at worst, “a bit too sloppy” in some of his appointments — chose to double down. He accused Wiesenthal, a supporter of the ÖVP, his Socialist party’s center-right opponents, of being politically motivated, and countered that, as a former prisoner of the Gestapo, he could forgive repentant former Nazis.

The row proved a prelude to a much sharper clash between the two men when Austria went to the polls again five years later. After the election, Wiesenthal published a dossier revealing that Friedrich Peter, the leader of the right-wing Freedom party with whom Kreisky had planned to form a coalition if the Socialists lost their majority, had been a member of an SS brigade that was implicated in the murder of 8,000 Jews.

Calling a press conference, the re-elected chancellor defended Peter and said that, 30 years after the end of the war, it was time “once and for all” to “erase the past.” He went on to claim that, having lost 21 members of his family in the Holocaust, he had the “moral right” to denounce Wiesenthal’s behavior. He also accused him of leading a “conservative Jewish mafia.” Kreisky capped his extraordinary statement by falsely implying that Wiesenthal might have been a Nazi collaborator. (When he repeated this libel 10 years later, the Austrian courts fined the then-former chancellor nearly $21,000).

While Israel’s diplomatic corps, viewing the row as a domestic matter, remained on the sidelines, Kreisky continued to throw out wild charges, asserting Wiesenthal was behaving “in the service of Israel.” Describing a subsequent phone call from the chancellor, the Israeli ambassador, Avigdor Dagan, reported back to Jerusalem “an unstopped flow of attacks and slander” in which Kreisky appeared “on the edge of insanity.”

The impact of Kreisky’s words was to shift the focus of the story from Peter’s past to Wiesenthal’s apparently malign behavior, as well as legitimizing Austrian press attacks — some of them loaded with antisemitic stereotypes — on the Nazi hunter.

As Aschheim writes, Kreisky’s behavior was “disproportionate and extreme, almost pathological.” There was a psychological dimension at play, he says. “He was so emotional that he exploded on anything to do with [Israel and Jewish matters]. It was always dramatic.”

Indeed, Aschheim quotes the Israeli historian Tom Segev’s suggestion that Kreisky regarded Wiesenthal less as a political opponent and more as “an enemy… [who] was a threat to his Austrian identity.”

“Such claims could not have been made by a non-Jewish person without being marked as antisemitic,” Aschhein says, adding that the chancellor’s background made his allegations against Wiesenthal appear “more objective, unbiased, and rational.”

Just over a decade later, and now out of office, Kreisky partially reprised this role when he defended Waldheim, the frontrunner for the Austrian presidency, soon after allegations of war crimes were leveled against him. The former chancellor accused the World Jewish Congress, which had led international opposition to Waldheim, of “exaggerated interference” in Austria’s domestic affairs, while noting that “it all happened a long, long time ago” during the embattled candidate’s youth.

As a former Socialist chancellor, international statesman, and Jew, his words carried special weight and were widely reported by a press which, once again, wasn’t above trading in thinly disguised antisemitic tropes as it laid into “improper interference by Jewish circles.” Waldheim himself used Kreisky’s comments as a shield to defend himself. But, as it had during the scandal surrounding Peter, Kreisky’s intervention also proved a useful distraction. “Instead of discussing Waldheim’s role in the war, discussion shifted to whether it was legitimate for ‘outsiders’ to intervene in Austrian issues,” writes Aschheim.

Waldheim was elected, but the affair began the process — long resisted by Kreisky but supported by younger Austrians — by which the country began to reassess its past. Aschheim admits that Kreisky’s decision to intervene in defense of Waldheim — a political opponent — was “the biggest mystery” in his research. “I couldn’t find an explanation for it,” he says.

Nonetheless, Aschheim has uncovered hints that, at the end of his life, Kreisky may have harbored regrets. In an emotional conversation with Barbara Taufar, a journalist and diplomat who served as his representative in Israel, the dying former chancellor reflected on the rise in antisemitism in Austria. “We just didn’t learn anything. Anything,” he told her.

As Aschheim’s book also makes clear, however, some of the controversies which surrounded Kreisky at the time are worth a second look.

On his watch and at his insistence, Austria had proven a vital place of refuge — and a staging post en route to Israel — for tens of thousands of persecuted Soviet Jews, a policy that made the country a target for terrorism. Kreisky’s heavy involvement, which stretched back long before he became chancellor, reflected his “Jewish conscience,” suggests one of those who worked with him on the issue.

But Kreisky’s commitment appeared to waver in September 1973 when Syrian-backed Palestinian terrorists held hostage three Jewish emigrants and an Austrian customs official at the Czech border. To the horror of Israel and the Nixon administration, the chancellor — citing his overriding duty to “save human lives at all costs” — bowed to the terrorists’ demands, allowing them to escape Austria and agreeing to close the Schönau transit camp. Golda Meir — who publicly denounced Kreisky’s deal with “these killers” — flew to Vienna where she and the chancellor had a furious row, as she accused him of bringing “renewed shame” on Austria and making himself the “hero” of the Arab world. The Israeli press was barely more diplomatic. “The devil knocked on the door, and the Austrians happily opened it,” declared one newspaper.

Again, Kreisky’s motives are disputed: was he primarily concerned with bringing the matter to a close without bloodshed or did the fact that Schönau was situated in an electorally important district that contained many former Nazis play into his calculations? Either way, as Meir herself conceded in her later memoirs, the ultimate outcome of the “Marchegg Incident,” as it was known, was not as problematic as it first appeared. While Schönau itself closed, Kreisky soon had other facilities up and running and, within four weeks of the attack, emigration from Russia through Austria reached the highest monthly figure recorded.

The emotional and angry exchange with Meir was hardly a one-off. Kreisky’s relations with Israel and its leaders were frequently fraught. He bridled at any suggestion that being Jewish should affect his attitude toward the country. “I cannot see,” he argued, “why the land of my real ancestors should be less dear to me than a strip of desert with which I have no ties.” Zionists, he said on another occasion, “welcomed antisemitism because it bore out their ideas.”

His attacks on the country and its governments were often brutal. Israel was a “police state that was run by men with a Fascist mentality.” Menachem Begin was “a little lawyer from Warsaw with the soul of a narrow-minded bookkeeper.” And his successor, Yitzhak Shamir, a “fascist” who “wished for the victory of Hitler.” By contrast, Kreisky adopted a somewhat indulgent attitude towards “outstanding” personalities like Syria’s Hafez al-Assad.

Observers frequently puzzled over the chancellor’s comments and behavior. One Austrian newspaper editor believed Kreisky was determined to “prove his Austrian ‘Kosherness’ by criticizing Israel,” while Israeli diplomats pondered that there was something irrational about his approach.

Nonetheless, argues Aschheim, there were “contradictions and deviations” in Kreisky’s attitude towards the Jewish state. He was, for instance, immensely proud of his nephew, Yossi, who served in the IDF and, in his eyes, represented the “Israeli humanistic creation.” On a less personal level, Begin — who, despite their ambivalent relationship, remained proud that a Jew could become chancellor of Austria “of all places” — felt no hesitation about turning to Kreisky to help negotiate the release of 20 Israeli soldiers taken hostage by Palestinian militants during the Lebanon war.

Like the Marchegg Incident, Kreisky’s approach towards the Israeli-Palestinian conflict perhaps now looks less antagonistic towards the Jewish state than some viewed it at the time. Undoubtedly, the chancellor’s sympathy for the Palestinians was often expressed with supreme insensitivity. Jews, he proclaimed, “should know better what it means to be expelled and robbed of their belongings.”

But, whatever view a person may have of the desirability or plausibility of a two-state solution, Achcheim says, Kreisky was a pioneer: he was the first European leader to back a Palestinian state and his recognition of the PLO was later followed by other Western states. At the same time, the author says, the chancellor took care not to undermine the legitimacy of the State of Israel, argued that two states were in the Jewish state’s best interests, and encouraged those in the PLO who favored negotiation with Israel.

Kreisky’s outlook, which is now mainstream on the European center-left from which he hailed, was ultimately not without consequence. Referring to the Oslo Accords, Shimon Peres came to believe that the Austrian’s efforts “prepared the ground for what was to come later.” The former president also believed that, despite Israel’s wariness about his desire to act as a mediator with the Arab states, “Kreisky played an important role in bringing Egypt and Israel together.”

Crucially, despite his opposition to Zionism, Kreisky came to recognize the importance of Israel. “Israel must have a future so that any Jews in the world could have refuge if ever a situation like the Holocaust should appear again,” he said to Taufar.

There was, Aschheim’s book deftly exposes, an irony underlying Kreisky’s complex and strained relationship with his own Jewish identity and the Jewish state. His closest friends were Jewish, his wife was Jewish, the intellectuals he loved and admired were Jewish.

“I think that, inside himself, he was a true Jew,” Menachem Oberbaum, a former Israeli journalist in Vienna told Aschheim. “I am sure he would not have liked to hear such a thing, but I insist that this is the truth.”

“Kreisky, Israel, and Jewish Identity” by Daniel Aschheim

This article contains affiliate links. If you use these links to buy something, The Times of Israel may earn a commission at no additional cost to you.

There's no paywall on The Times of Israel, but the journalism we do is costly. As an independent news organization, we are in no way influenced by political or business interests. We rely on readers like you to support our fact-based coverage of Israel and the Jewish world. If you appreciate the integrity of this type of journalism, please join the ToI Community.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel