Heirs of Nazi-persecuted collector hail justice in auction of Edvard Munch painting

Prof. Curt Glaser sold ‘Dance on the Beach’ under duress in the 1930s. Now, the 1906 masterpiece is expected to fetch $15-25 million after a deal was struck with the current owner

Edvard Munch, 'Dance on the Beach.' (Reinhardt Frieze). (Courtesy of Sotheby's)

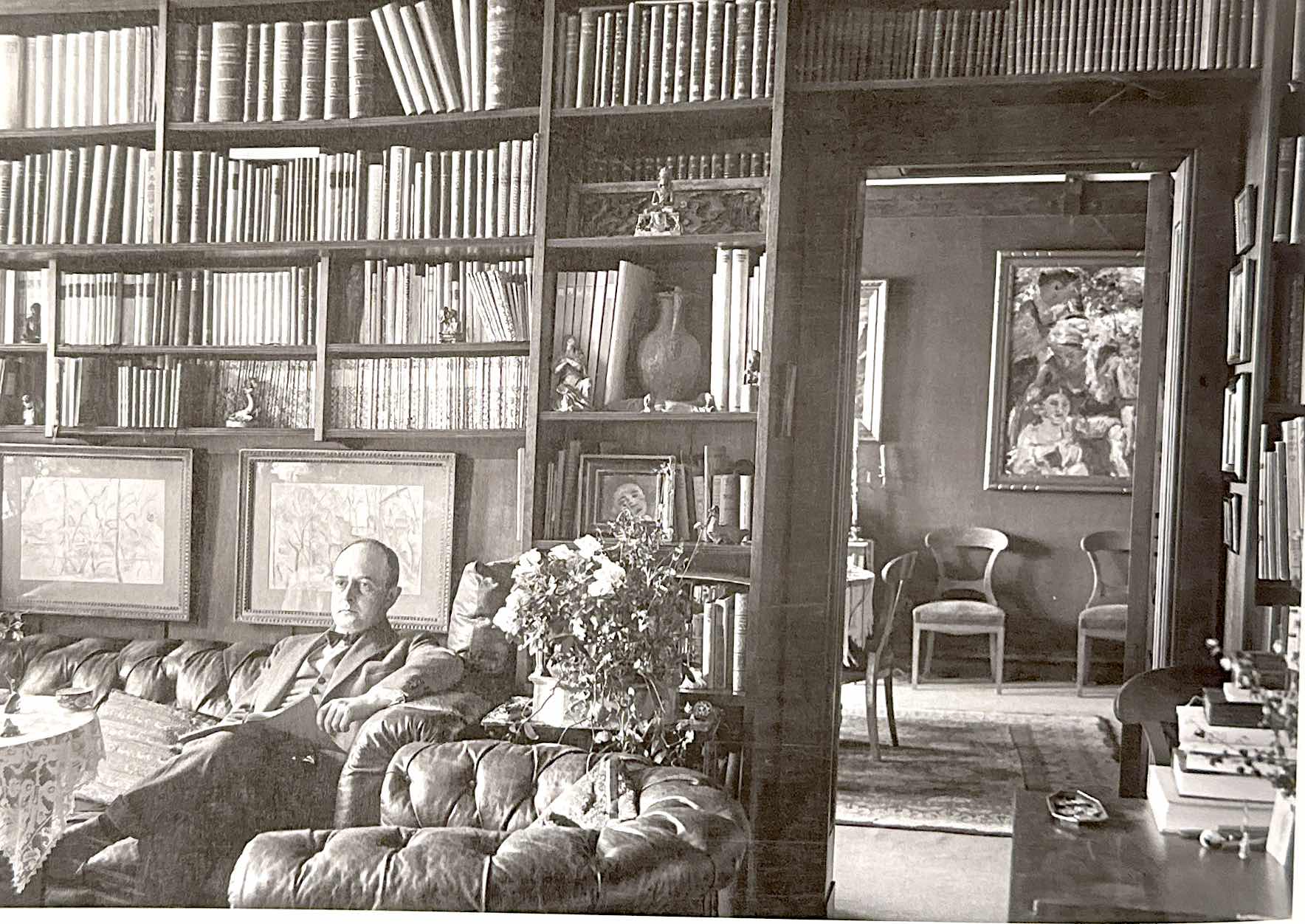

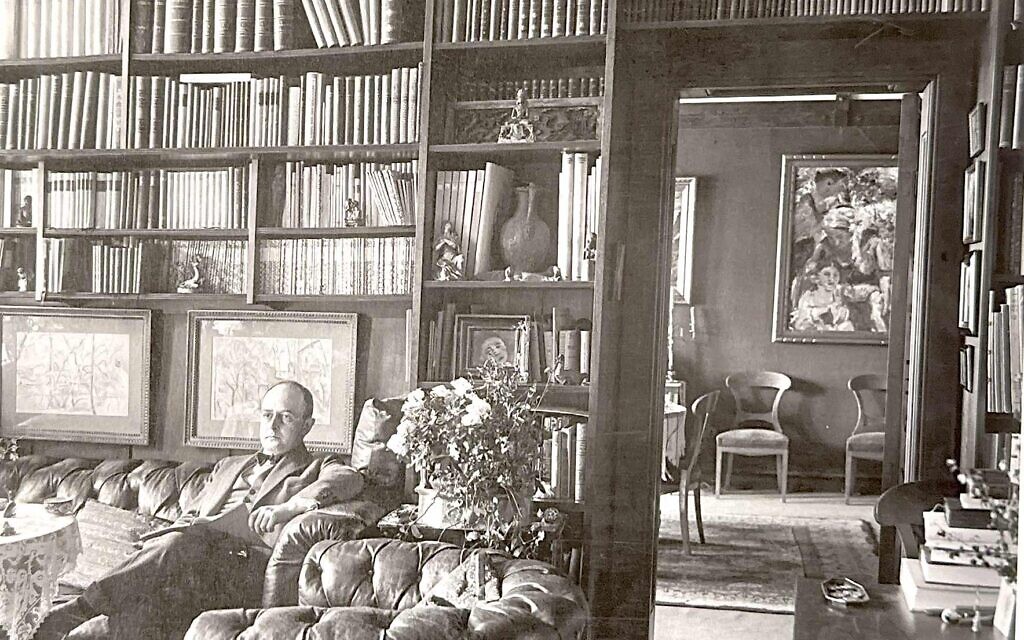

Edvard Munch, 'Dance on the Beach.' (Reinhardt Frieze). (Courtesy of Sotheby's) Prof. Curt Glaser sitting in his study in an undated photo. (Courtesy of Sotheby's)

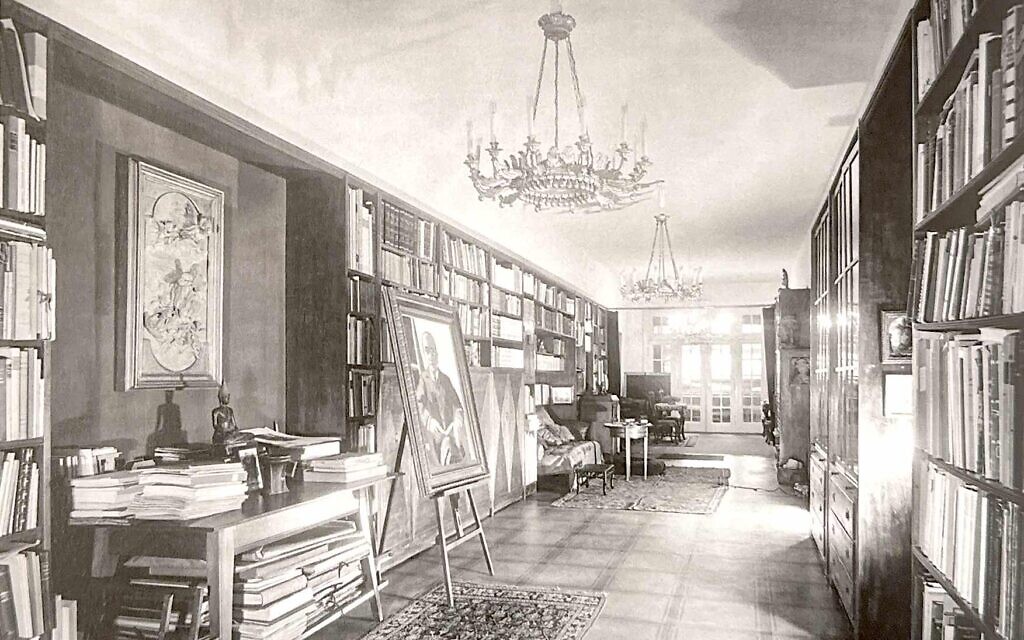

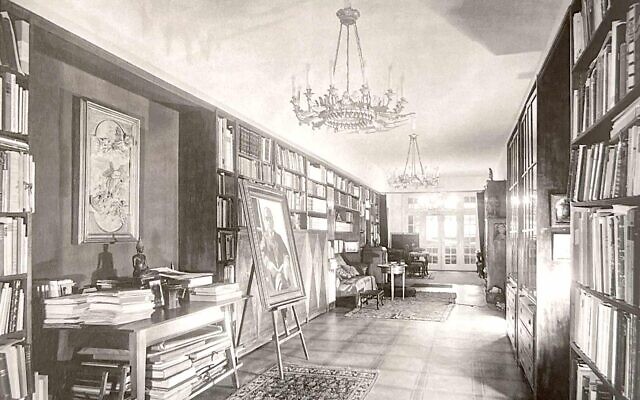

Prof. Curt Glaser sitting in his study in an undated photo. (Courtesy of Sotheby's) An undated photo of Curt Glaser's library in his apartment with a Tiepolo on the wall and a portrait of Glaser by Max Beckmann on the easel. (Courtesy of Sotheby's)

An undated photo of Curt Glaser's library in his apartment with a Tiepolo on the wall and a portrait of Glaser by Max Beckmann on the easel. (Courtesy of Sotheby's) Edvard Munch (back seat left) and Curt Glaser (driving) and wife Elsa (standing) in Oslo (then called Kristiana) in August 1913. (Courtesy of Sotheby's)

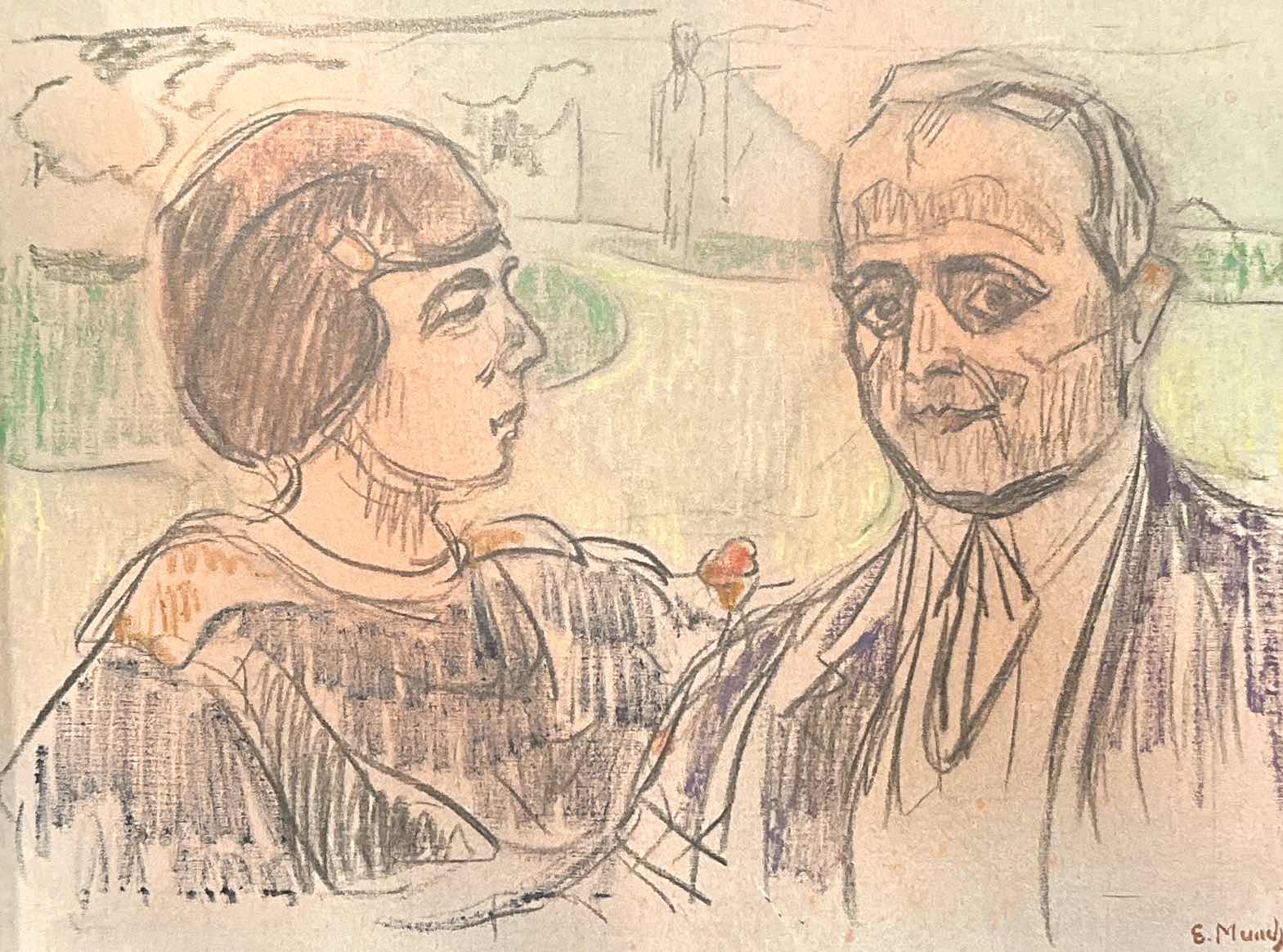

Edvard Munch (back seat left) and Curt Glaser (driving) and wife Elsa (standing) in Oslo (then called Kristiana) in August 1913. (Courtesy of Sotheby's) Sketch of Elsa and Curt Glaser by Edvard Munch drawn in 1913. (Courtesy of Sotheby's)

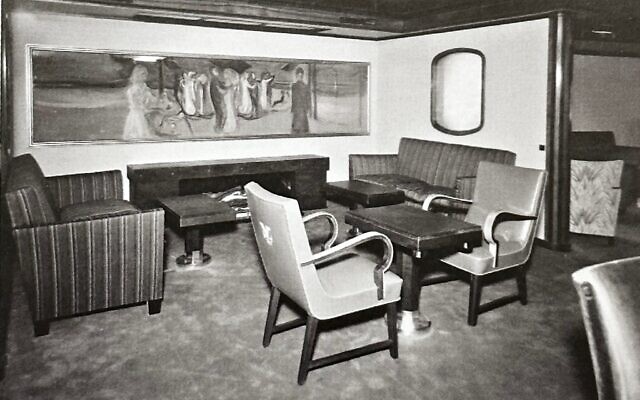

Sketch of Elsa and Curt Glaser by Edvard Munch drawn in 1913. (Courtesy of Sotheby's) The painting 'Dance on the Beach' photographed on the MS Black Watch in 1939. (Courtesy of Sotheby's)

The painting 'Dance on the Beach' photographed on the MS Black Watch in 1939. (Courtesy of Sotheby's)

LONDON — An expressionist masterpiece by Edvard Munch, which a renowned German Jewish art expert was forced to sell less than four months after Hitler came to power, is expected to sell for $15-$25 million when it comes up for auction in London next week.

“Dance on the Beach” is going under the hammer on March 1 as part of an agreement between the heirs of Prof. Curt Glaser and those of Norwegian shipowner Thomas Olsen. Olsen acquired the painting at a sale in Oslo in 1934.

Both Olsen — who stowed the painting in a forest barn after the Nazis invaded Norway six years later — and Glaser were friends and patrons of Munch.

The artwork was originally commissioned by the famed Jewish impresario Max Reinhardt for his Berlin avant-garde theater at the turn of the 20th century.

“This exceptional painting is made all the more special due to its extraordinary provenance, a history that has unfolded since it was painted 115 years ago,” said Lucian Simmons, Sotheby’s Vice Chairman and Worldwide Head of Restitution, in a press statement. “Intertwined in the story of this painting are two families — both leading patrons of Munch.”

Sotheby’s has arranged for the painting to go on public display for the first time in more than 40 years in London from February 22 through the auction on March 1.

David Rowland, a lawyer representing the Glaser family, praised the Norwegians’ handling of the case, calling it “exemplary.”

“The Glaser heirs want to first and foremost thank Petter Olsen for reaching a fair and just settlement with the Glaser heirs in a very correct and humanistic way,” Rowland told The Times of Israel. “His treatment of the Glaser heirs has been exemplary. Additionally, the Glaser heirs want to thank Sotheby’s for their expertise and professional handling of this matter.”

The painting was part of a pioneering 12-panel work — now known as “The Reinhardt Frieze” — commissioned in 1906 and designed as an immersive installation in the Berlin theater’s upper level. “Audience members were immersed in Munch’s vision — which he titled ‘images from the modern psyche’ — before stepping into Reinhardt’s performance space,” Sotheby’s explained in a media briefing.

However, in 1912 the theater was refurbished and the frieze split into its component parts. Glaser, a central figure in the Berlin art world and friend of Munch, acquired the “Dance on the Beach.” It became part of a collection — which included other works by Munch, Henri Matisse, and Max Beckmann, as well as important Old Master paintings — assembled by Glaser and his wife, Elsa.

The couple shared an enthusiasm for art, traveled extensively and hosted a weekly salon in their apartment in Berlin’s Prinz-Albrecht Strasse. A year after acquiring “Dance on the Beach,” Glaser and Elsa visited Munch in Oslo for the first time.

Champions of Modernism

An internationally known art historian and expert, Glaser published the first German monograph on Munch and became art editor of the daily newspaper Berliner Börsen-Courier, as well as editor of Kunst und Künstler, a monthly art review. Aside from his work on Munch, Glaser published books on a range of other artists, including Paul Cézanne and Hans Holbein. His professional career peaked with his appointment in the 1920s as director of the Berlin State Art Library. Glaser and Elsa, who died in 1932, later came to add modernist art and drawings — particularly expressionist works, like those of Munch — to their collection.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Glaser was swiftly placed on leave and then fired from his post at the Berlin State Art Library. In May 1933, the art expert was forced from his apartment — in a building which came to house the Gestapo headquarters — and much of his collection was auctioned in Berlin. Glaser and his second wife, Maria Milch, left Germany for Switzerland soon afterward. In 1941, the couple emigrated to the United States. Glaser died in New York in 1943 aged just 64.

Within months of Glaser’s departure from Berlin, “Dance on the Beach” went on auction in Oslo and was purchased by Olsen. Like Glaser, the Norwegian was a friend and patron of Munch. As Simmons notes: “So important were the Glasers and the Olsens to Munch, that he painted both Henrietta Olsen and Elsa Glaser.”

Olsen, who was also a neighbor of Munch, gave “Dance on the Beach” pride of place in the first-class lounge of the MS Black Watch, which ferried passengers between Oslo and Newcastle, in the northeast of England, between January and September 1939.

But when war broke out, Olsen suspended the service, laid the passenger liner up, and removed the artwork. “Dance on the Beach” was one of around 30 works by Munch owned by Olsen, including one of four versions of his famous painting, “The Scream.” Fearing a German invasion, Olsen decided to place his Munch masterpieces in hiding in a barn in a Norwegian forest.

After the Nazis’ defeat, Olsen recovered “Dance on the Beach” and his other treasured artworks. It has remained in the hands of the Olsen family since 1945 and is the only part of the original Reinhardt-commissioned frieze still in private hands. Nine of the pieces are held in the collection of Berlin’s National Gallery, one in the Hamburg Kunsthalle and one in Essen’s Folkwang Museum.

The importance of the artwork in Munch’s turbulent life and career is underlined by Sotheby’s. The auctioneer’s Vice-Chairman of Fine Arts, Simon Shaw, said in a press statement: “Munch was the ultimate rebel, and every brushstroke on this frieze is utterly modern and purely expressive. This composition reimagines one of Munch’s greatest images, the ‘Dance of Life,’ which was the culmination of the artist’s ‘Frieze of Life’ and places love at the centre of the artist’s ‘modern life of the soul.’”

He added: “This work is among the greatest of all Expressionist masterpieces remaining in private hands — its shattering emotional impact remains as powerful today as in 1906.”

“Dance on the Beach” was the last work that Munch — who lost his mother and a sister to tuberculosis as a child and whose father suffered severe depression — completed before he suffered an acute breakdown in 1908.

Posthumous professional recognition

For Glaser, the Nazi takeover was shattering. His precious collection was broken up and his glittering career was effectively over. As a publication by Basel’s Kunstmuseum explains: “Glaser was unable to regain a professional foothold either in Switzerland or in America.”

Nonetheless, the Kunstmuseum’s recent exhibition “The Collector Curt Glaser: From Champion of Modernism to Refugee” represents a first step in reviving his reputation and showcasing his accomplishments. It displayed 200 works from Glaser’s collection — acquired in the 1933 auction — together for the first time since the collection was sold off. Rowland describes the exhibition as “magnificently done and … a great way to honor Professor Glaser’s legacy.”

The exhibition itself was part of a restitution settlement reached between the Glaser family and the city of Basel in 2020. That settlement came 16 years after the Jewish collector’s heirs had first approached the Canton of Basel-Stadt and made a claim to some of the artworks. The city rejected the claim but when the family made a second approach in 2017, the museum’s board of trustees launched an investigation. It concluded that Glaser had indeed sold his collection due to persecution. The heirs and the city reached an agreement under which the museum retained the collection, paid the family an undisclosed sum, and agreed to stage an exhibition about Glaser’s work.

As the New York Times reported in 2021, since 2007, 12 private collectors or individuals have agreed with the city of Basel that Glaser sold his collection as a result of Nazi persecution and either returned artworks or paid compensation. Among their number are the Dutch Restitutions Committee, the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation in Berlin, and the Museum Ludwig in Cologne.

Rowland confirmed that the Glaser heirs are engaged in a number of other current restitution claims.

However, as the Times also reported, some institutions — including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston — have adopted a more skeptical approach, arguing that it is not clear that Glaser was forced to sell his artworks.

Rowland describes the museums’ position as “illogical and indefensible.” He is similarly critical of the UK’s Spoilation Advisory Panel decision in June 2009 regarding the Glaser family’s claim for eight drawings in the collection of the Courtauld Institute of Art, London. The panel seeks to resolve claims from people, or their heirs, who lost possession of cultural property during the Nazi era that’s now held in UK national collections. However, while it deemed the “predominant reason” for Glaser’s sale of the drawings in 1933 to be “Nazi oppression,” it concluded that the “moral claim was insufficiently strong to warrant the transfer of the drawings.”

But, as Rowland argues, shortly after the panel’s decision, the Terezin Declaration — a non-binding agreement by 47 countries — ruled that forced sales fell within the terms of the landmark 1998 Washington Conference on Holocaust-era assets and were entitled to a “fair and just solution.” The UK panel has, however, refused requests by the Glaser heirs to revisit their decision. “We think that now, given the many positive Glaser decisions and given the Basel exhibition, and now this important Munch sale in London, this would be an ideal time for them to do so,” says Rowland.

Theft by any other name?

The Glaser case exemplifies the fact that, over the past decade, the number of restitution cases involving forced sales, as opposed to straight-up looting by the Nazis, has risen, says Christopher A. Marinello, CEO and founder of Art Recovery International. He attributes the shift to both the courts showing a greater willingness to recognize the validity of such cases and the heirs of Jews who were forced to sell off their possessions becoming more aware of the legitimacy of their claims.

“These types of cases are a little more difficult than the outright cases involving looting, but they are just as important,” Marinello stresses. “Many of these families just unloaded artworks because they had to. They needed money to flee and unfortunately there were all too many people, including disreputable dealers, who were looking to capitalize on this and looking to profit off the misery of Jewish families.”

Marinello, who has assisted many Jewish families in their fight for justice, notes too that agreement on the Munch painting appears to have been reached without recourse to the courts.

“It’s always the goal to keep these types of cases out of the courtroom. Litigating is extremely time-consuming, it’s extremely expensive … and the results are uncertain,” he says.

There is, though, a more important reason why such agreements are better made away from the glare of publicity protracted legal cases attract.

“The families don’t want to go through the pain of the Holocaust again,” Marinello says. “They don’t want to relive everything that their families went through and they don’t want to read about it in press reports.”

There's no paywall on The Times of Israel, but the journalism we do is costly. As an independent news organization, we are in no way influenced by political or business interests. We rely on readers like you to support our fact-based coverage of Israel and the Jewish world. If you appreciate the integrity of this type of journalism, please join the ToI Community.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel