An early Zionist’s unsolved murder fuels a mystery novel ripped from the archives

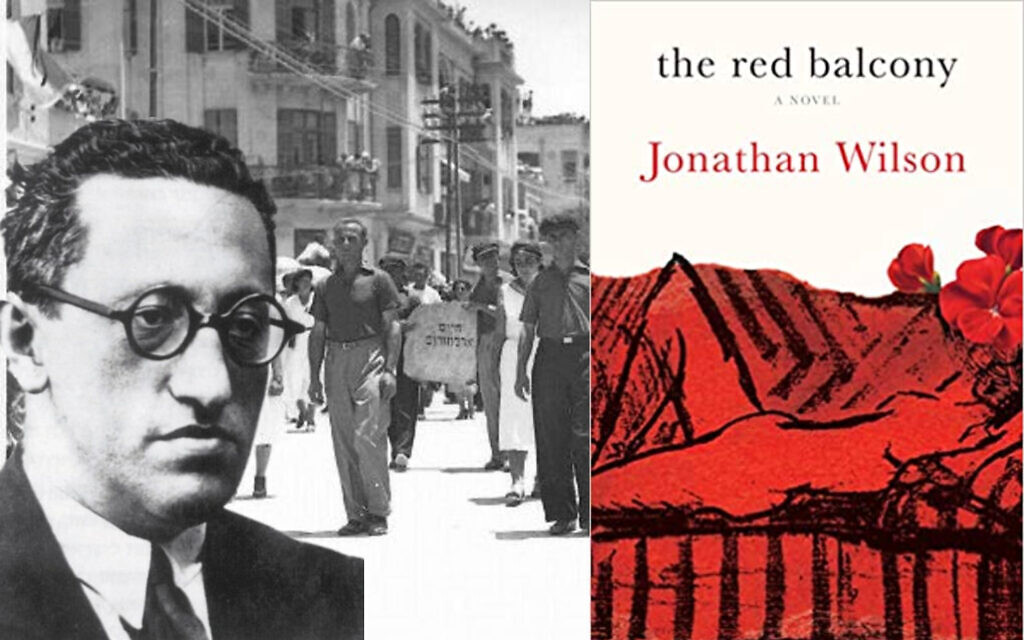

The slaying of Haim Arlosoroff 90 years ago remains controversial. What will Jonathan Wilson’s characters make of this unsolvable crime in ‘The Red Balcony,’ on shelves now?

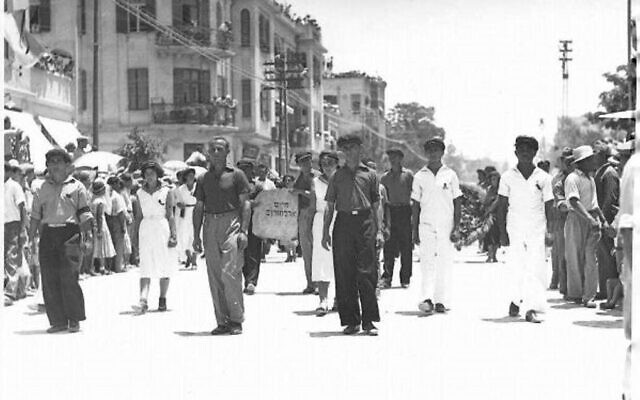

LONDON — It is the great whodunnit of Zionist lore. On a balmy summer evening in June 1933, Haim Arlosoroff was shot dead by an assassin as he walked along a Tel Aviv beach with his wife.

At 34, Arlosoroff was head of the Jewish Agency’s political department and a rising star in the Zionist movement. Multiple theories exist, but the identity of his killer has remained shrouded in mystery for the past nine decades.

The assassination forms the backdrop to “The Red Balcony,” a sizzling tale of murder and high politics, sex and betrayal by novelist Jonathan Wilson. The book hit shelves on February 21.

While some have pointed the finger of blame for Arlosoroff’s killing at Arab nationalists and even Nazi propaganda minister Josef Goebbels, the cloud of suspicion initially centered on right-wing supporters of Ze’ev Jabotinsky. Just days before he was murdered, Arlosoroff had returned from Berlin where he had helped negotiate the controversial Ha’avara, or “transfer,” agreement with Hitler’s newly installed government.

It allowed German Jews to emigrate to Palestine with some of their assets but required that those assets be used to purchase German exports. Jabotinsky, the leader of the Revisionist movement, and his followers were fiercely opposed to the agreement, which they viewed as supping with the devil and breaching the international boycott of the Nazi regime which Jewish organizations had advocated.

But while the right virulently attacked Arlosoroff — a leading light in Mapai, a forerunner of the Israeli Labor party — as a traitor, local Arabs viewed him as the man responsible for sealing a deal that potentially opened the floodgates to a surge of Jewish refugees into the country.

Wilson’s novel loosely tracks the real-life case of two Russian Jews — Avraham Stavsky and Ze’ev Rosenblatt — who were tried for the murder in the spring of 1934. Rosenblatt was cleared, but Stavsky was initially found guilty and sentenced to death. The Appeal Court eventually overturned the conviction due to lack of corroborating evidence. But the legal process didn’t shake the left’s view of the Revisionists as murderers, nor the right’s certainty that it was the victim of a politically inspired blood libel.

But much of the action in “The Red Balcony” surrounds a host of fictional characters: Ivor Castle, a young Jewish graduate of Oxford University, who travels from his upper-middle-class home in London to take a position as assistant to the misanthropic and cynical defense counsel Phineas Baron; Tsiona Kerem, a mysterious, free-spirited artist whose critical witness testimony Castle is sent to secure but with whom the inexperienced lawyer falls hopelessly in love; Charles Gross, an Oxford contemporary of Castle’s and staunch Zionist; and his American cousin, Baltimore debutante Susannah Green. Through their intertwined stories, Wilson deftly explores questions of identity, law and politics.

The British-born Jewish writer, who lived in Jerusalem in the late 1970s and now lives in Massachusetts, admits to being “drawn to and fascinated by” the short, unhappy and, in the UK, oft-forgotten story of the interwar British Mandate in Palestine. “The Red Balcony” is the third time — following the critically acclaimed “A Palestine Affair” and “The Hiding Room” — he has returned to the subject.

“I often feel when people discuss the history… they don’t go back far enough to look at those early years of the Yishuv, the state in waiting, and the conflict that was occurring, and to see Palestine for what it was then, which was really… a miniature outpost of the British Empire,” Wilson tells The Times of Israel.

Mandate Palestine, he continues, was “a fascinating mix of characters and individuals and historical figures and competing narratives.” That fascination, in part, rests on the fact that “the country hadn’t yet settled.”

“Nothing was fixed and everything was up in the air and up for grabs,” Wilson says. “Different individuals had completely different thoughts about what the future was going to be and how it would work itself out and what the state was going to be.”

But why the Arlosoroff murder?

“Of all the political events, machinations, maneuvers and assassinations that occurred in that period,” Wilson says, “the Arlosoroff murder is probably the most significant.”

Indeed, he believes, the killing continues to have a resonance today.

“It still plays a significant role in Israeli political consciousness,” the novelist says, noting that when corruption allegations were first leveled against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, one of his aides responded: “Next they’ll accuse him of murdering Arlosoroff.” Perhaps more substantively, Wilson believes it was the event in Israeli political history that “cemented the schism between the left and the right that is still in evidence today.”

History repeating itself

Wilson says one of the “catalysts” for his decision to write about the killing was the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin in 1995. At the time, he remembers, there was much talk about the uniqueness of the crime — of a Jew assassinating another Jew for political reasons — despite the fact that this may well have occurred in the Arlosoroff case, and did occur in the 1957 murder of Israel (Rudolf) Kastner, who was accused of collaborating with the Nazis.

“There’s a precedent and the same split,” Wilson notes. “The furor against Rabin that was unleashed in Zion Square [where an infamous protest took place in which Rabin was depicted in an SS officer’s uniform] was very similar to the furor unleashed against Arlosoroff in 1933. The future is held in the past in some way.”

Wilson is keenly aware of the controversies surrounding the Transfer Agreement and the need to treat the subject with sensitivity to avoid providing “fodder for antisemites.”

“From a novelistic point of view, is so filled with ambiguity that it’s a subject that invites the kind of depth that fiction can bring,” he says.

Wilson tries throughout the book to avoid putting words in the mouths of the actual historical figures who feature in its pages, but he nonetheless allows Arlosoroff to muse upon the moral complexity of the Transfer Agreement. “It was an ugly, unsavory deal,” the novel has the Zionist leader think to himself, “but how else could the Jews purchase their freedom to leave?”

“I tried to tell the truth about it and tried to present the differing responses to it via my characters as accurately as I could,” Wilson says. “One can see why the Revisionists were so enraged. One can also see why Arlosoroff and his group were trying to save lives.”

In all, some 50,000-60,000 German Jews are thought to have escaped a then uncertain fate at the hands of the Nazis.

“As a writer of historical fiction, if I’m writing about the aftermath of the murder of Haim Arlosoroff, I can’t elide the complexities of the responses to the Transfer Agreement,” Wilson says. “I have to present them as they were.”

So who dunnit?

Wilson adopts the same evenhandedness when discussing his thoughts about who the culprits behind Arlosoroff’s killing might have been. “I wanted to keep my mind open for the purpose of writing the fiction,” he says.

He underlines the multiple twists and turns in the case that feature in the book. Arlosoroff’s wife, Sima, for instance, initially suggested her husband’s assailants were Arabs, before later claiming they were Jews. The defense’s contention that Arlosoroff had been murdered in the course of a failed sexual assault on his wife appeared to receive a boost when a young Arab man provided a detailed confession. But the man, who was in prison on another murder charge, later retracted his claims, saying he had been bribed by Stavsky and Rosenblatt to confess. And, while it receives only the briefest of nods in the novel, there have also been suggestions that Goebbels had Arlosoroff killed because of rumors that his wife, Magda Goebbels, had had a youthful relationship with the future Zionist leader when he lived in Berlin. (Before Arlosoroff emigrated to Palestine, the pair had been close friends, having met as teenagers through Haim’s sister, Liza).

Ultimately, Wilson keeps his own thoughts on the perpetrators to himself, instead preferring to quote the words of Chekov: “The task of a writer is not to solve the problem but to state the problem correctly.” He does, however, believe that the truth behind the assassination is now unlikely to ever emerge. Indeed, a commission established by Menachem Begin to examine the killing — which the then-prime minister hoped would exonerate the Revisionists — failed to come to a conclusion about the identity of the real killers. Wilson describes the 90-year-old case as “frozen in aspic” with viewpoints about who was responsible unlikely to be shifted.

“It’s not as if some new evidence is going to show up that is going to conclusively prove it one way or the other,” Wilson says.

Conflicting loyalties

The novel also successfully delves into the conflicting loyalties and identities of Mandate Palestine.

Castle, for instance, feels no particular affinity with the Jews in Palestine or the country itself, is largely indifferent to the cause of Zionism, and feels no sense of allegiance to the Yishuv. “He’s sort of on an adventure,” says Wilson, “but he starts to question himself when he’s there and question his identity.”

By contrast, Gross is an ardent Revisionist Zionist and supporter of Jabotinsky, regards Castle as flippant and naive, and sheds no tears over Arlosoroff’s murder. The two men, believes Wilson, thus in many regards represent the polarities of British Jewry’s response to Zionism and Palestine during the interwar years.

But Castle’s lack of interest in Palestine or Zionism doesn’t mean he’s not keenly aware of his own Jewishness. In Britain, says the book, he feels like “an interloping guest.”

“There’s no denying an antisemitic undercurrent that he’s experienced in England,” says Wilson.

At the same time, however, he recognizes that his home country has hardly stifled the aspirations and success of his family, with their home in London’s wealthy St. John’s Wood and Oxford-educated children.

Further complexity and color are added by Baron — “loyal to no one but himself,” in the words of the novel — who, despite being a British Jew, regards the Jews, Arabs and British themselves with equal dollops of derision.

As Wilson notes, the British administration in Palestine was ideologically heterogeneous, containing within its ranks British Jews who were supporters and opponents of Zionism, as well as non-Jewish British officials who were sympathetic to the aspirations of the Jews for statehood, while others were decidedly Arabist in their inclinations.

But Wilson also recognizes that the book’s subject and characters aren’t without personal resonance.

“I’m drawn to this period not only because the history is so fascinating but for personal reasons because … these issues relate to maybe conflicts about my own British Jewish character,” he explains. “I am interested in the pulls, tugs and pushes of these different issues of identity which seemed so fluid in that period and continued for me when I lived in Israel 40 years ago.”

This article contains affiliate links. If you use these links to buy something, The Times of Israel may earn a commission at no additional cost to you.

There's no paywall on The Times of Israel, but the journalism we do is costly. As an independent news organization, we are in no way influenced by political or business interests. We rely on readers like you to support our fact-based coverage of Israel and the Jewish world. If you appreciate the integrity of this type of journalism, please join the ToI Community.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel