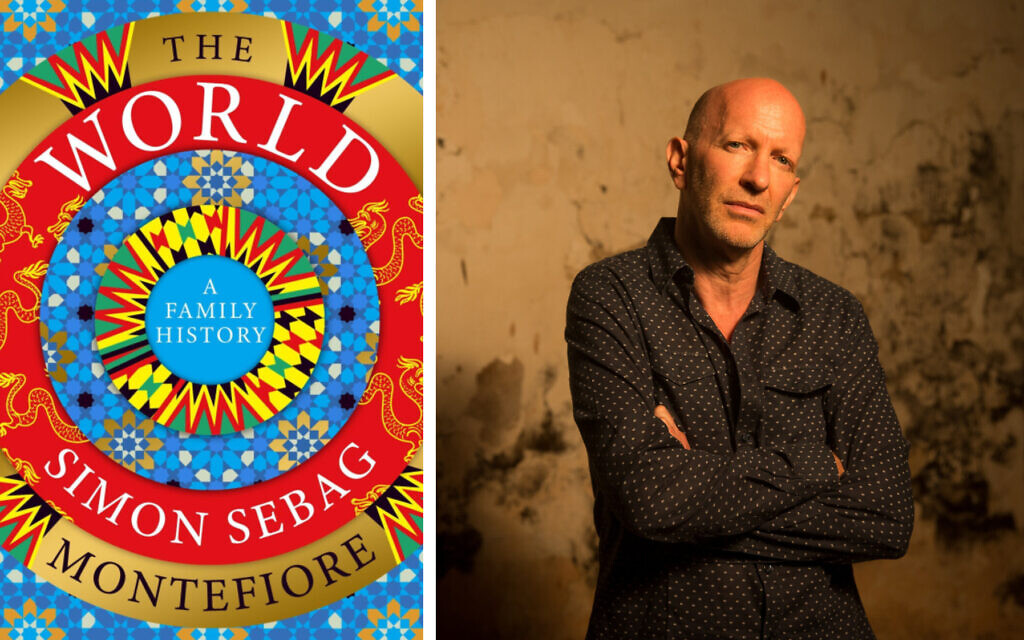

New world history by pop-historian Simon Sebag Montefiore is a family affair

‘The World: A Family History’ charts a millennia-long epic from the Caesars to the Trumps. Sir Moses’ descendent explains how PM Netanyahu may have just made a historical blunder

LONDON — The word family, Simon Sebag Montefiore writes in his new history of the world, conjures “an air of cosiness and affection.”

But much of “The World: A Family History” is anything but.

In 1,300 pages, the renowned Jewish historian, a descendant of Sir Moses Montefiore, tells the epic story of the world through the families who have shaped and dominated it. From the Caesars to the Trumps, via the Medicis, Ottomans, Hapsburgs, Rothschilds, Kennedys, Pahlavis, and Assads, it oozes blood and betrayal, sex and savagery.

“The stories that I tell are absolutely brutal. Family life can be cozy and affectionate — it can also be murderous incestuous and degenerate,” Montefiore tells The Times of Israel. “When power is personal, the prizes are personal — but so are the costs.”

The “power institutions” — whose lurid stories provide the book with a sense of drama and spectacle often lacking from the somewhat dry genre of world history — are very different from the traditional nuclear family.

Egyptian pharaoh “Fatso” Ptolemy VIII dismembered his son and sent the parts to his child’s mother; Cleopatra celebrated her first night with Anthony, Montefiore writes, “in Ptolemaic style — with Bacchic banquets and sibling murder” — she had Anthony murder her twin sister Arsinoe. And the French Queen, Catherine de’Medici, orchestrated a massacre at her daughter’s wedding.

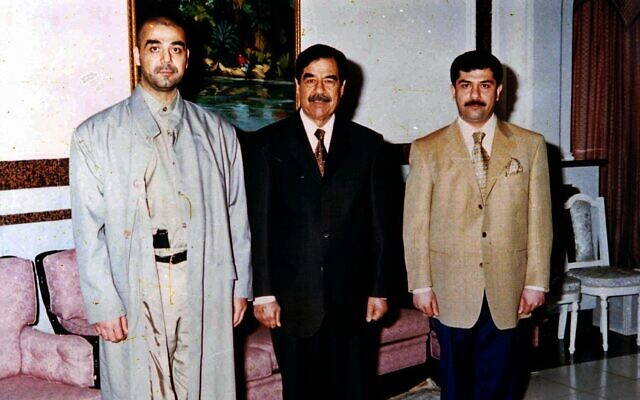

This familial carnage, though, is not just ancient history. Montefiore describes how in the 1990s, for instance, Saddam Hussein’s son, Uday — “a Caligularian psychopath with a speech impediment” — engaged in a bloody feud with his sisters’ husbands, the Kamel brothers, who, having defected to Jordan, were lured back to Iraq and murdered. More recently, Kim Jong-un had his half-brother assassinated using a nerve agent at an airport in Malaysia.

Montefiore, the author of acclaimed biographies of Catherine the Great, Joseph Stalin and the Romanovs, says his history of Israel’s capital, “Jerusalem: A Biography,” served as an inspiration for his newest book. In it, he writes, he attempts to chronicle the city’s story “through the lives of the men and women — soldiers and prophets, poets and kings, peasants and musicians — and the families who made Jerusalem.”

“In many world histories there’s a lot about trade routes, commodities and technical advances, and the human factor is often lost,” he says. “What I’m trying to do here is to combine the span of world history with the intimacy, the grit, the juice of biography.”

Telling the story of the world through families also allows Montefiore to bring a greater cast onto the stage. “Women play a big part in families and family history is a way to treat women equally and fairly,” he says. “It seems like a traditional device to talk about dynasties, but when you open up diversity and gender it turns out to be a very 21st-century device.”

The book thus sees Montefiore introduce readers to a plethora of lesser-known female power players — many of whom turn out to be just as ruthless and murderous as their male counterparts.

“There are all the familiar female characters — Cleopatra, Catherine the Great, Margaret Thatcher — but you’ll also find a whole lot of other female characters who should be just as familiar to us but aren’t,” he says.

The family device also enables the horror of slavery — “an anti-family institution,” in Montefiore’s words — to be woven into the fabric of the story.

One such — perhaps unfamiliar — character is Anastasia, a 17th-century enslaved Greek odalisque in the harem of the Ottoman sultan, Ahmed I. He named her Kösem and, after the pair were married, she came to wield huge power. She would eventually order the strangulation of her son, and was herself later strangled on the orders of her grandson.

Actually in world history as a whole women are no better and no worse than men

Is female leadership better than that of men? Montefiore is unconvinced. “I think a lot of our view of female leadership is influenced by the views of today,” he says. “Much of that reflects the fact that you have amazing Scandinavian prime ministers like Sanna Marin in Finland, who are very impressive, but actually in world history as a whole women are no better and no worse than men.”

Montefiore says he has tried to avoid becoming drawn into the culture wars in which, particularly in the United States and Britain, history has become part of the battlefield.

“I made a deliberate effort not to accommodate it. I think this is the most diverse world history ever written, I think it’s the most female-friendly,” he says. But, the historian continues, “I have deliberately rejected any ideology that might impose a polemical view on history, which is always wrong.”

I try to tell the stories of as many of the innocents killed, enslaved or repressed as I can: everyone counts or no one counts

Thus he laments the fact that “the old childish history of ‘goodies’ and ‘baddies’ is back in fashion, albeit with different ‘goodies’ and ‘baddies.’” Instead, Montefiore adopts a simple principle: “Achievements and crimes are chronicled, whoever the perpetrators were,” he writes. “I try to tell the stories of as many of the innocents killed, enslaved or repressed as I can: everyone counts or no one counts.”

Indeed, unlike many world histories, which are heavily focused on Europe, Montefiore paints on a much broader canvas. Latin America, Africa and Asia, at last, receive their due.

Montefiore also rejects the idea that dynastic rule is either an anachronistic notion or the preserve of dictatorships. He reels off countless examples of “demo-dynasties” — not just the Kennedys, Bushes, and Nehru-Gandhis but more current examples such as the Marcoses in the Philippines, Kenyattas in Kenya, and Bhuttos and Sharifs in Pakistan. These elected dynasties, which Montefiore believes offer voters a sense of “reassurance, continuity and the prestige of a well-known political family” can — albeit sometimes with a bit more effort than usually required in liberal democracies — be turned out of office.

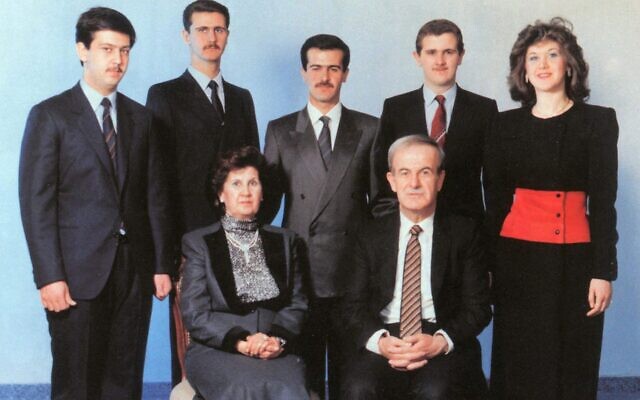

That’s not the case, of course, with the “family autocracies” which are so prevalent in the Middle East. Montefiore brilliantly captures the blood-soaked rise and spectacular survival of Syria’s Assad family, not least Bashar al-Assad who, at the age of 28, the book introduces as “tall, lanky, chinless with a lisp and a liking for Phil Collins music — an unlikely candidate for dictator.”

But, Montefiore says, as the killing fields of the war-ravaged country testify, despite their “Western manners,” the president and his wife, Asma, turned out to have “inherited the ruthlessness of his father and the family.” The Assads, he continues, have become a “typical modern monarchy.”

A rather more benign monarchical institution — the British Royal Family — is one that Montefiore is himself close to. A friend of King Charles III, he describes the new monarch as “a very unusual person in any constitutional dynasty,” citing his “visionary” campaigning on climate change two decades before any other world leader began discussing the issue. “A lifetime model of service and duty and responsibility,” Montefiore believes “there’s a lot of continuity with his mother; basically, we’re very lucky to have him.”

Constitutional monarchies work because the monarch personifies the constitution … [providing] an apolitical institution representing the state

More widely, he suggests the Windsors’ enduring popularity in the UK stems from the fact that, like a number of other European constitutional monarchies, the royal family “is extremely flexible and always reflects the society that it represents.”

“That’s the genius of the system,” he adds. “The constitutional monarchies in Britain and Holland and other northern European countries work because the monarch personifies the constitution … [providing] an apolitical institution representing the state.”

But aren’t such systems outdated and irrational? Montefiore is unpersuaded and counters with the example of Israeli democracy “where [the] rules allow tiny parties to dominate the country.” This system, like so many other democracies with their own idiosyncrasies, is “hardly rational either.”

Montefiore’s updated edition of “Jerusalem: The Biography” brings Israel’s story up to the age of the Abraham Accords and Benjamin Netanyahu. He believes the normalization agreements reveal “the dawn of a new era… where Israel becomes a more Middle Eastern country in many ways.”

“I think it will remain a democracy — a very messy, unsatisfactory democracy with many flaws — but it remains a unique country in the Middle East in terms of… its real democracy,” he says.

Montefiore knows Netanyahu personally and the incoming prime minister — “a great reader of history” — has read his books. He labels Netanyahu’s willingness to form a coalition with the far-right “a terrible decision.”

“His decision to allow these fascists into the government is a disaster and will permanently spoil his reputation historically,” Montefiore believes.

But while he believes the far-right poses “a real threat” to democracy in Israel, he doesn’t believe it will do permanent damage and he cautions against singling the country out.

[Netanyahu’s] decision to allow these fascists into the government is a disaster and will permanently spoil his reputation historically

“Israel is a democracy and people voted for these people and, in many ways, the pattern of this just fits into what is happening in the world — in Brazil, in America, in Italy,” he says. “Israel is just a normal country that has the same follies as other countries — but we don’t have to like it.”

Montefiore’s harsh words about Netanyahu contrast with his warm assessment of the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky. “The World: A Family History” concludes with the Russian invasion of its neighbor. Many, he writes, had believed the former actor “too soft to handle his dictatorial antithesis.” But Zelensky — one of the few Jewish leaders in the world, Montefiore notes — has proven “one of the great war leaders of all time” and “that rare thing: a hero on the world stage.”

He draws a comparison with Britain’s wartime leader, Winston Churchill. “Just as Churchill sent the English language into battle to help democracy, Zelensky has done the same, but with the internet,” Montefiore says. Montefiore believes the Ukrainian president has “created a new template for leadership brilliantly. He is a unique figure. He’s remarkable in all sorts of ways.”

As one of the foremost British historians of Russia, Montefiore views Vladimir Putin’s ultimate fate as uncertain. The Russian president, he says, will survive and remain in power until he dies if the war evolves into “endless stalemate.” However, he believes that, if Ukraine decisively defeats Russia, Putin “will be removed in some sort of palace coup and judging by Russian history — if you look at the fates of Peter III, Paul I and [Lavrentiy] Beria in 1953 — that could be messy.”

The final pages of Montefiore’s book — dominated by the pandemic, Putin, and the threats of nuclear war and climate change — are bleak in many ways. But he disputes the popular notion that these are unprecedented times. It is the 70 years of European peace that ended with Putin’s aggression against Ukraine which are exceptional, he argues. The invasion, he grimly remarks, represents “a return to service as usual.” Similarly, he believes that the “lessons of 1945” — the evils of antisemitism and the crimes of genocide and war-making — as well as the freedoms of Western democracy are having to be “fought for again.”

Nonetheless, Montefiore remains an optimist. For all their flaws, open societies remain “the happiest and freest” places to live. “The harshness of humanity has been constantly rescued by our capacity to create and love: the family is the center of both,” he writes. “Our limitless ability to destroy is matched only by our ingenious ability to recover.”

And Montefiore leaves the final word to a quote from Anne Frank: “Think of all the beauty still left around you and be happy.”

This article contains affiliate links. If you use these links to buy something, The Times of Israel may earn a commission at no additional cost to you.

There's no paywall on The Times of Israel, but the journalism we do is costly. As an independent news organization, we are in no way influenced by political or business interests. We rely on readers like you to support our fact-based coverage of Israel and the Jewish world. If you appreciate the integrity of this type of journalism, please join the ToI Community.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel