In London exhibition, snapshots of Jewish life soon to be shattered by the Holocaust

The Wiener Library’s display of Jewish refugee family photos, running through November 4, shows happy times – and dark clouds on the horizon

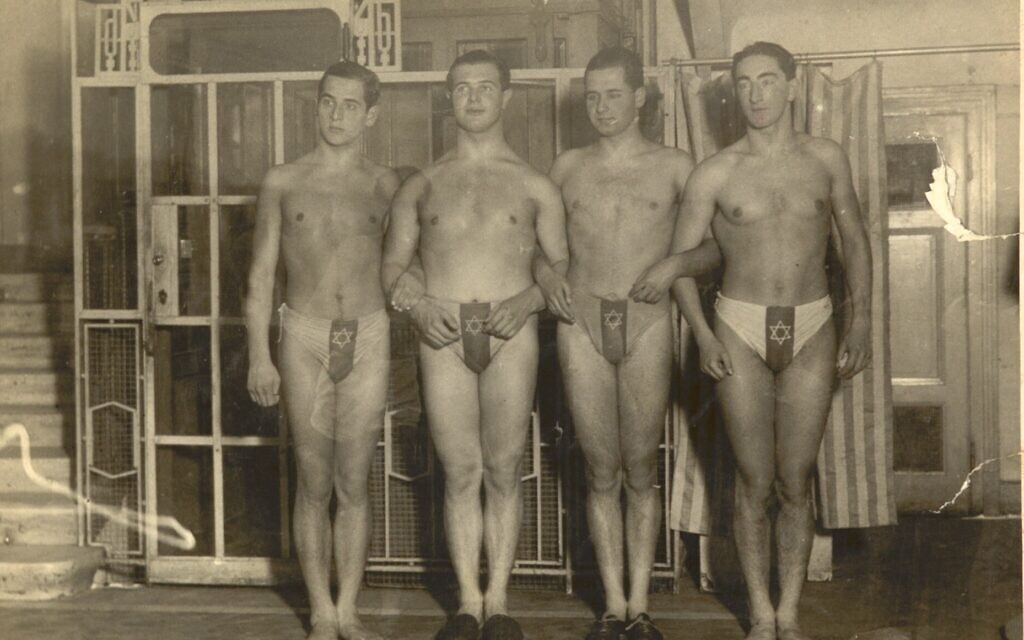

Hubert Nassau's photo of the Hakoah swim team from the 1920s. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections)

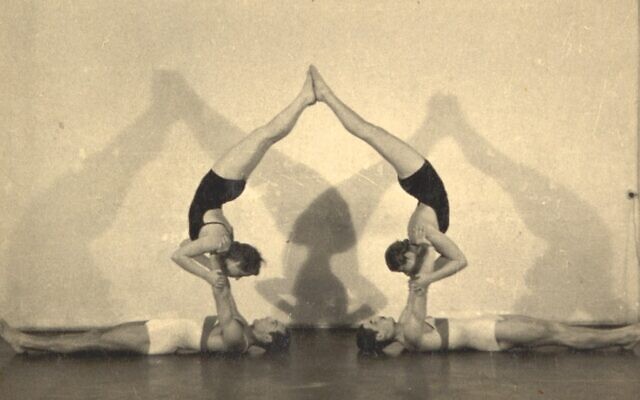

Hubert Nassau's photo of the Hakoah swim team from the 1920s. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections) A photo taken by Ernst Levy in the 1910s or 1920s. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections)

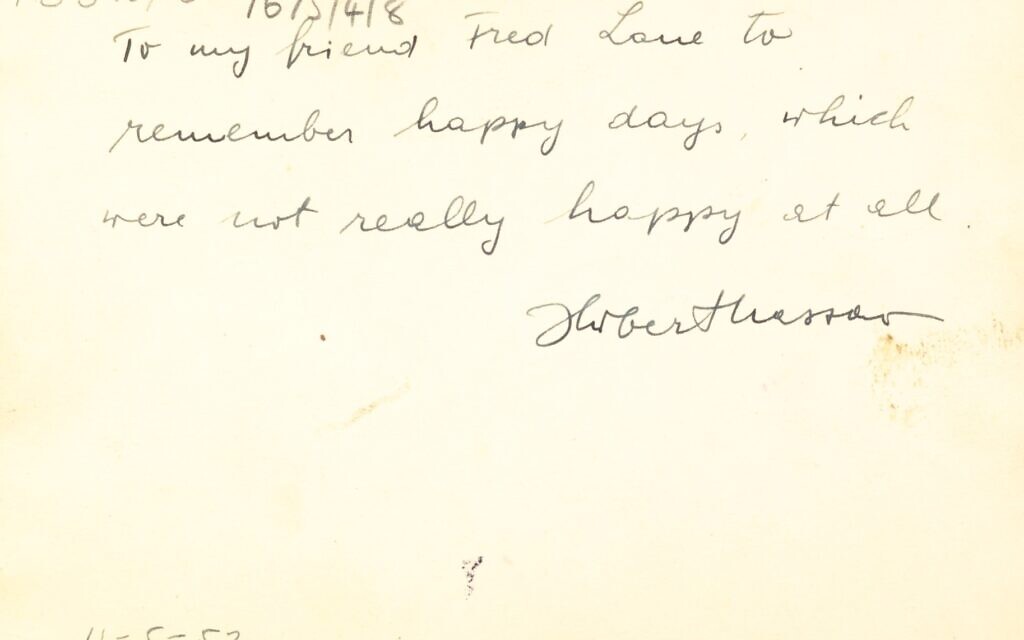

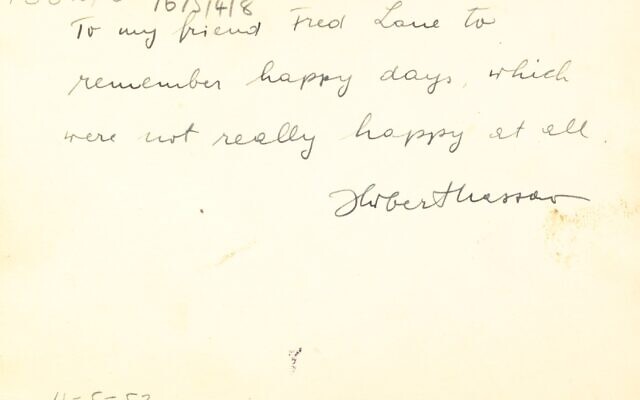

A photo taken by Ernst Levy in the 1910s or 1920s. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections) The inscription on the reverse side of Hubert Nassau's photo of the Hakoah swim team. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections)

The inscription on the reverse side of Hubert Nassau's photo of the Hakoah swim team. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections) Ludwig Meumann, in uniform at far left, with his family circa the 1910s. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections)

Ludwig Meumann, in uniform at far left, with his family circa the 1910s. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections) Dorothea Jacoby, circa 1911. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections)

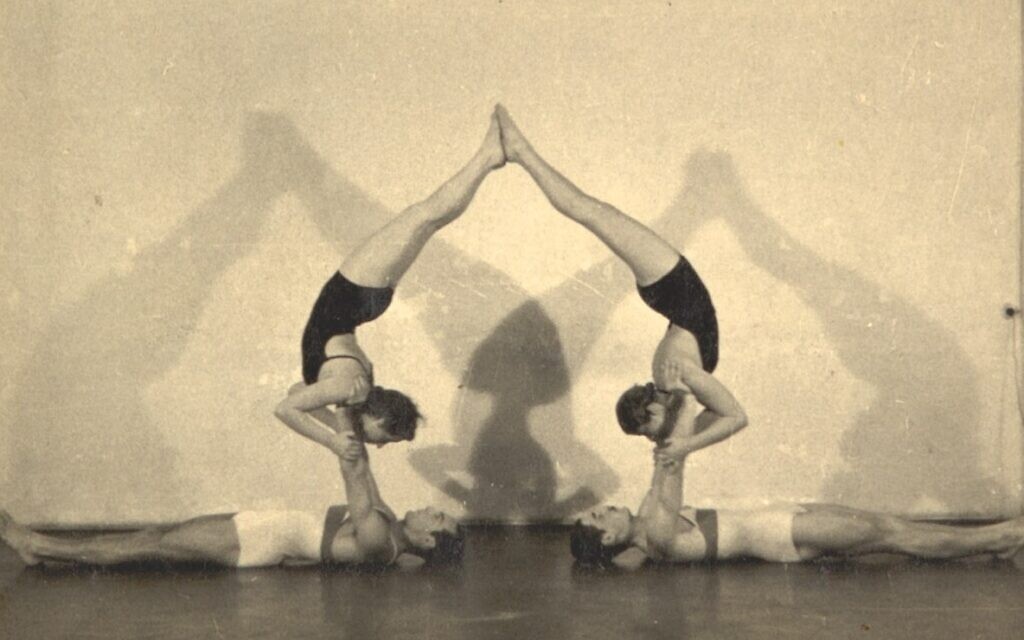

Dorothea Jacoby, circa 1911. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections) Gymnasts from the 1930s, Lisette Pollak is at top left. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections)

Gymnasts from the 1930s, Lisette Pollak is at top left. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections) A photo taken by Ernst Levy in the 1910s or 1920s. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections)

A photo taken by Ernst Levy in the 1910s or 1920s. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections) A photo taken by Ernst Levy in the 1910s or 1920s. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections)

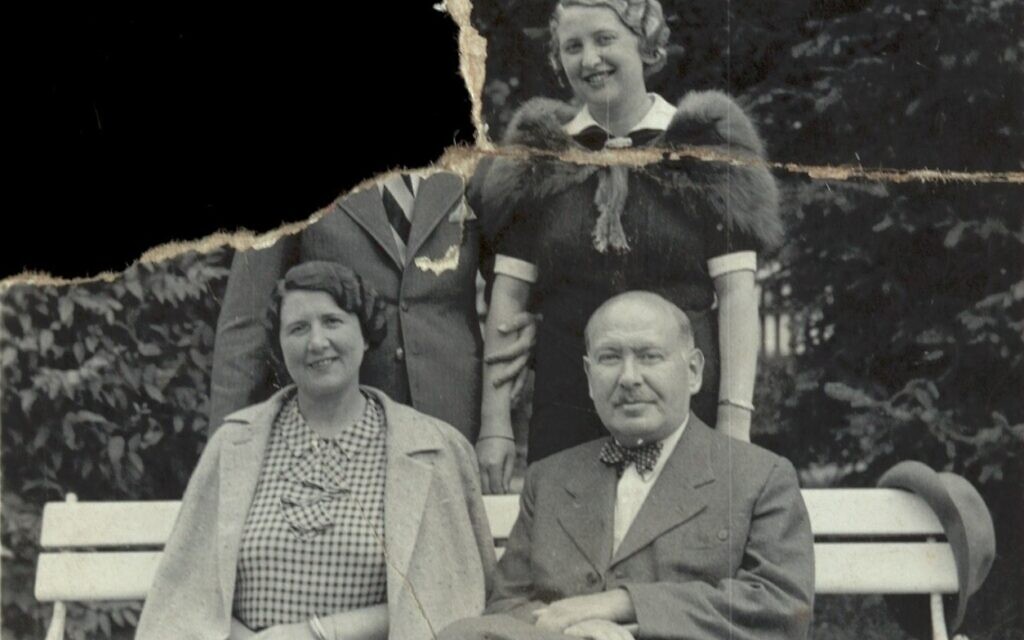

A photo taken by Ernst Levy in the 1910s or 1920s. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections) Gertrude Glaser with her parents in the 1930s. Her ex-husband has been torn out of the photo. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections)

Gertrude Glaser with her parents in the 1930s. Her ex-husband has been torn out of the photo. (Wiener Holocaust Library Collections)

LONDON — “To remember happy days, which were not really happy at all,” reads the inscription on the back of a photograph of a Jewish swim team taken moments after its victory in a championship.

The image of the Vienna-based Hakoah team in the late 1920s was owned by Hubert Nassau. The message was sent by him to fellow teammate Fritz Lichtenstein seven years after the defeat of the Third Reich.

Like Lichtenstein, Nassau managed to escape the Nazis’ effort to annihilate European Jewry, emigrating to Britain months after the Anschluss.

Nassau’s picture — and an equally striking one of his future wife, fellow Jewish refugee Lisette Pollak, demonstrating her gymnastic prowess in the 1930s — feature in a powerful new exhibition, “’There was a time…’: Jewish Family Photographs Before 1939,” at London’s Wiener Holocaust Library.

The exhibition draws on Wiener’s archive of over 700 family papers collections — the largest related to Jewish refugees from Nazi Europe in the UK. Donated over the years by Jewish refugees and their families, the treasure trove includes extensive collections of photographs: portraits, snapshots and albums.

“Photographs like these are all too often overlooked or used as illustrations for other materials rather than considered seriously as important documents and artistic works. This exhibition aims to change this thinking,” says Helen Lewandowski, an assistant curator at the library. “I was fascinated by the different ways in which everyday, commonplace photographs were used to fashion identity, assert agency and belonging, and facilitate memory for Jewish families.”

Naturally, some of the images are heartbreakingly poignant. An elegant portrait shows Dorothea Jacoby, likely taken in 1911 by her husband, Ludwig, shortly after their marriage. The couple had two children: Henny and Hans-Bernd. While Henny managed to escape to Britain in 1938, Dorothea, her husband and son were deported to Auschwitz in 1943 and murdered.

An undated caption on the back of the photograph, which may have been written by Henny, says simply: “Es war einmal.” While this is usually translated as “Once upon a time,” and used to start a fairy tale, the exhibition title adopts a more literal and ambivalent translation: “There was a time.”

The family of Ludwig Liebermann was rather more fortunate than that of Jacoby. After serving in World War I, Liebermann obtained a chemistry doctorate and worked in various industrial firms in Germany and abroad. But in 1936, six years after his marriage to Susan Friedmann, Liebermann was warned by his manager that, because the company would no longer be able to protect a Jewish employee, he should not return from his next business trip abroad. The following year, Susan and his children joined him in Britain. After their naturalization in 1947, Susanne and Ludwig Liebermann anglicized their names to Susan and Louis Linton.

The images collected by Liebermann for his two children, Eva and Albert, cover the period from the 1890s to the 1970s, although many are from 1905-1906 and capture Ludwig’s childhood in Berlin. Others show him as a young man out of the army but still in uniform with his mother on their boat in 1919, as a student at Berlin University, and at work in his first job as a research chemist. Still others, taken in the decade leading up to 1937, show Liebermann as a proud young father. But there is also a chilling foretaste of what is to come: a picture captures him standing beside a Nazi election poster from which Hitler’s face stares out menacingly.

Before his death in 1980, Liebermann had diligently typed captions for the pictures. But piecing together the stories behind the images — even the identity of the people in them — isn’t always so straightforward.

“Sometimes, the donor of a collection will supply us with extensive information about their family, their photographs and those depicted, but at times, particularly if photographs have come to us after the photographer has died, the information is sparser,” says Dr. Barbara Warnock, the library’s senior curator and head of education. “Often [we] cannot identify everyone — and sometimes anyone — in the images.”

Nonetheless, even images without captions and context can be captivating. Ernst Levy, who grew up in an affluent, middle-class family in Berlin at the turn of the century, trained as a lawyer and became a partner in his father’s timber business. As recently digitized negatives dating from the 1910s and 1920s demonstrate, Levy was also a skilled amateur photographer. According to the exhibition, “even with generic and touristic subjects, Ernst Levy experimented with light, framing, texture, odd juxtapositions, and classical tropes.”

After his father’s death and the seizure of the company by the Nazis, Levy left Germany in 1938. He was assisted by his future wife, Helen Thilo, who he had met on a business trip to Switzerland. Born in England to German parents, Thilo grew up in Hamburg and Berlin, before using her British passport to return to the UK in 1937. The exhibition also contains Thilo’s photo album, which shows a trip to Brandenberg in 1936. One of the images which displays an antisemitic street sign reading “Jews are not welcome in the Fürstenberg health resort!” is sarcastically captioned by Thilo as, “The first greeting!”

Of course, reaching the safety of Britain did not free the refugees from trauma, loss and grief. Pictures from the collection of Mathilde Politzer, who was born to a middle-class family in Vienna, show her posing as an alpine peasant in studio portraits from 1910-11. Twenty years later, her daughter, Elisabeth Eisner, is seen in snapshots taken by friends in a meadow on the city’s rural outskirts around 1937. Elisabeth, who lost her job as a shorthand typist after the Nazis walked into Austria in 1938, left the country for Britain on a domestic service visa six months later. On the eve of war in August 1939, Elisabeth was able to arrange for her mother to follow her to the UK. But her father, Mathilde’s former husband, Josef, was deported to Riga in 1942 and murdered.

A more visual representation of the strain placed on the marriages of some refugees as they fled their homes and went into exile is provided by a photograph that belonged to Gertrude Glaser. Glaser, whose father was of Jewish descent and whose mother was Catholic, married Jewish manufacturer Emil Glaser in 1933. After the Anschluss, the family’s assets were seized and Gertrude’s parents, brother and husband imprisoned. In April 1939, Gertrude and Emil Glaser emigrated to Britain. Two years later, however, their marriage deteriorated, leading to a protracted divorce in the late 1940s. In the image — taken in the 1930s and showing Gertrude, Emil and her parents posed around by a park bench — Glaser has been ripped out.

“Ripping a photograph is such a visceral, charged act,” says Lewandowski. “It speaks to how family photographs aren’t just images — they are physical objects that have been handled and returned, sometimes many years later, to make sense of the past and to react to trauma.”

But it is the normal, routine and everyday — of happy families, people holidaying or enjoying their sporting achievements and leisure pursuits — which is more evident in the exhibition.

Playful studio portraits of Wally Bock and her parents taken around the 1910s, for instance, show the family, which emigrated to Britain in the late 1930s, dressed as figures from German folklore. Others show Ernst Kamm, a businessman who fought for the German army in WWI and registered as a member of the Home Guard in the 1930s, dressed in traditional hunting regalia. The 14 studio portraits were taken following a competition run by the Deutscher Schützenbund, a national German shooting sports club, around May 1929. Just under a decade later, Kamm was imprisoned in Buchenwald after Kristallnacht. He was released only on condition he immediately leave Germany.

As many other images in the exhibition show, contrary to the antisemitic lies promoted by senior members of the military establishment after its defeat in 1918, Kamm was hardly unique among German Jews in having fought for their country during WWI.

“Studio photographs showing soldiers in their uniforms have often been preserved by their descendants,” notes Warnock. “The generation of German Jews that served during the First World War were often patriotic and identified strongly with their country.”

None of the people shown in the exhibition were left untouched by the tragedy which befell Jews in Europe barely months after some of the images were taken. It’s a stark reminder their loyalty and patriotism were returned by their country in the cruelest manner imaginable.

There's no paywall on The Times of Israel, but the journalism we do is costly. As an independent news organization, we are in no way influenced by political or business interests. We rely on readers like you to support our fact-based coverage of Israel and the Jewish world. If you appreciate the integrity of this type of journalism, please join the ToI Community.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel